Symposium re-enters ‘Secular City’

Cox’s book still provocative after all these years

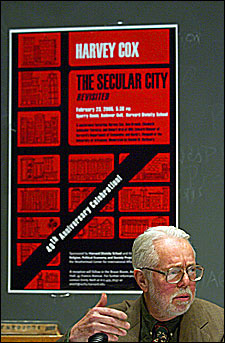

Forty years ago, when he wrote “The Secular City,” Harvey Cox, the Hollis Professor of Divinity, had a hard time finding a publisher. The book was initially rejected, and when it was accepted, by Macmillan, it was on the condition that 5,000 copies – half the print run – be sold by the National Student Christian Federation, for whom Cox had written the book as advance reading for an upcoming conference. Today, on the 40th anniversary of its publication, the book has sold more than 1 million copies and has been translated into 14 languages. “I only wish I’d signed an escalation contract!” Cox said, smiling ruefully at a symposium given in his honor on Feb. 23.

The book, simple in style and comprehensive in scope, posits that secularism is not necessarily the negative force it has often been considered, but has positive outcomes as well, including preventing religion from becoming too powerful and allowing people to choose from a wide variety of worldviews. God, Cox maintained, can be just as present in the secular as in the formally religious realm of life. By emphasizing social justice and questioning the authority of not only religious but also social and political institutions, the slim volume resonated with civil rights and antiwar protesters, incipient feminists, politically involved students, and post-Vatican II Catholics.

The Feb. 23 conference celebrated the book’s fourth decade as an influential voice on the Harvard campus and beyond. The range of its author’s voice was celebrated as well. In the early 1980s when he started teaching “Jesus and the Moral Life,” Cox was the first Harvard professor to bring the question of “living the good life” back to course work in more than a half-century, and it turned out to be wildly popular with students. Many of his books – including the most recent, “Common Prayers” – explore in greater depth the issues introduced in “The Secular City,” including urbanization, the explosive growth of Pentecostalism worldwide, and Jewish-Christian relations.

Participants in the conference – which was held in a packed Sperry Room at the Divinity School – included Anne Braude and Elisabeth Schussler Fiorenza, both of the Divinity School; Edward Glaeser of the Kennedy School and the Faculty of Arts and Sciences; and David L. Chappell, associate professor of history at the University of Arkansas. Moderated by Rachel McCleary of the Weatherhead Center, the symposium’s format allowed 10 minutes for each speaker before turning to a response from Cox and then questions from the audience.

Each speaker focused on a different aspect of the book while placing it in the context of both the social forces at work in the 1960s and the theological revivals of recent decades. Fiorenza introduced the notion of “The Secular City” as a “protofeminist” work because it conceptualized a spirituality without the “domination and exclusion” inherent in traditional religions and because of its characterization of urban environments as “spaces where Christians and all people could come of age” and fulfill their potential through the anonymity, mobility, and tolerance of city life. Though the idea was that those who were different would not be demonized for their views, she added, today the secular city “seems no longer a place of no religion at all, but the marketplace of reactionary religions.”

Glaeser called the book a “starting point for a formal theory of interaction between cities and ethics.” He mentioned not only the anonymity that makes it more difficult to enforce traditional norms and the mobility that allows people to move “from social group to social group,” but also noted the diversity of urban areas, which allows people to “reach across boundaries” while assisting the movement of ideas – including those of reactionary religions – from person to person.

One of the evening’s main themes was that of social justice. Can mayors and other city officials be ethical leaders without driving away the rich, or is their job merely, as Glaeser put it, to “make sure [they’re] not screwing up on snow removal”? How much must suburbanites sacrifice in order to improve or erase the ghettos that Cox labeled “urban concentration camps”? Did the liberals of the 1960s and ’70s alienate the middle class by seeming to attack traditional values? Why do Christians feel more comfortable giving to the poor through religious institutions than through their tax dollars?

Cox conceded that in his youthful exuberance he wrote a book whose “argument is nothing if not sweeping,” and admitted that looking back, he wondered how he could have been so hyperbolic. He decided, however, that “maybe at a certain stage in life you ought to be hyperbolic. Later on, you’ll calm down and try not to be too evocative, not to overgeneralize.” He bemoaned, however, that graduate students today seem much less willing to take risks than were his counterparts, many of whom, Braude pointed out, saw his book as a call to action.

While Cox was quick to point out – for the hundredth time, no doubt – that he was “quite mistakenly” grouped with the ‘death of God’ theologians,” he did question the depth of religious fervor in the world today, and asked in particular why “the religious right has captured the public argument in such a dramatic and disappointing way.” He believes it is imperative that intellectuals keep the lines of conversation open and attempt to engage the nation’s Jerry Falwells and Pat Robertsons in an honest interfaith dialogue. He added that the religious right is not a monolithic group, and that the red state/blue state dichotomy currently in vogue is not nearly as cut and dried as the media – or the American Civil Liberties Union, or the Christian Coalition – would have us believe.

“The question,” he concluded, “is who owns theology? One of the things ‘The Secular City’ and other books did was open the conversation about theological issues to all kinds of people. The arena of discourse in which theology goes on was changed, and it would no longer be experts deciding on the answers; the populace was now demanding to be part of the discussion, and I think that’s still going on. And if that’s the only thing that this little red-covered volume contributed, then that’s enough.”