Reading between the lines

Former congressman lends perspective to redistricting plan

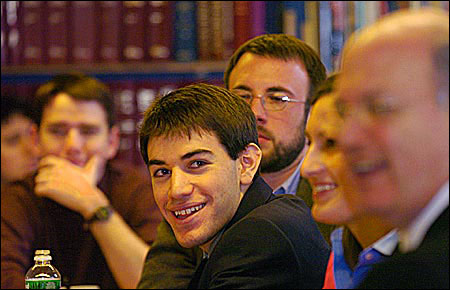

An Institute of Politics student policy group got some expert advice about legislative redistricting Monday (Feb. 28) from a veteran on the front lines: an incumbent congressman voted out of his seat after a round of redistricting before the 2004 election.

Former U.S. Rep. Martin Frost, a longtime Democratic representative from Texas, spoke to Harvard undergraduates on the Institute of Politics Redistricting Policy Group about a plan the students drafted that would reform the way redistricting is done in the United States.

The meeting was one of three events planned for Monday (Feb. 28) around the topic of redistricting. Other events included a meeting with Iowa Secretary of State Chet Culver, Washington Post Editorial Page Editor Fred Hiatt, Common Cause President and Chief Executive Officer Chellie Pingree, Rutgers Professor Alan Rosenthal, and an evening panel discussion at the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum featuring Culver, Hiatt, Pingree, Rosenthal, and Harvard Law School Professor Lani Guinier.

Redistricting is an arcane governmental exercise meant to ensure that representation in state legislatures and in Congress remains fair despite population growth, migration, and other demographic changes over time.

Redistricting can also be used as a political weapon, however, in a process called gerrymandering, where districts are drawn to favor candidates of the party in power or to protect incumbents of both parties.

Harvard sophomore Eric Lesser, co-chairman of the Redistricting Policy Group, said the group formed last year when the three co-chairs, Lesser, Paul Davis, and Joshua Patashnik, felt that recent events in Texas indicated the time for redistricting reform may be ripe.

Though redistricting is typically done every 10 years – after the census – the Texas legislature conducted a mid-decade redistricting in 2003 after changing hands from a Democratic majority to a Republican majority.

Texas’ congressional district lines were redrawn to favor Republican candidates and last fall’s election highlighted their success. Several targeted Democrats lost, including Frost, a 13-term congressman who was defeated by incumbent Republican Peter Sessions after a bitterly fought campaign that became one of the most expensive congressional races in U.S. history, with both sides together spending more than $9 million.

Lesser said what was alarming about the Texas redistricting was not that it was so partisan – Democrats have been equally adept at redrawing district lines to favor their own candidates – but that it occurred mid-decade.

That, combined with a U.S. Supreme Court decision that appears to indicate a hands-off attitude toward redistricting challenges, opens the door to a constant round-robin of redistricting across the country, occurring whenever power shifts from one party to the next and weakening a representative’s connection with his or her constituents, who may shift into another district in the next round of changes.

The reform plan, drafted by 20 students in the Redistricting Policy Group, would take the process out of the hands of state legislatures, which currently handle redistricting in a majority of states. Instead, it would establish redistricting commissions, as currently done in a handful of states.

The seven-member commissions would be selected by party leaders in the state Senate from a pool of citizens – Republican, Democrat, and unaffiliated – created by the state Supreme Court. Following basic guidelines, the commission would deliberate privately until it presented a redistricting plan to the legislature. The plan would automatically go into effect unless rejected by two-thirds majority of both houses.

“The basic idea is to have a commission system that separates decision-making authority from the people directly involved,” Lesser said.

Frost and Harvard Law School Professor Heather Gerken, who also attended the meeting, both praised the students’ work. Frost offered some practical advice in getting the plan passed, such as including House leaders in the appointment process. He also disputed whether a feature in the plan that would have Senate leaders appointing members of the other party to the board would be effective at creating a moderate commission or whether it would just create credibility problems for the commission member.

“You’ve made an ambitious run at a very thorny and difficult problem,” Frost said.

Both Frost and Gerken debated the students’ contention that the U.S. Supreme Court won’t rule on future redistricting cases, saying that the court has left the door open – albeit slightly – to ruling on such cases.

Gerken said she thought the plan was not ambitious enough, especially since its best chances of passage would be in states with ballot initiative where it would bypass the legislative process in many states.

IOP Director Phil Sharp said policy groups such as the one on redistricting give students a chance to look at particular subjects in great depth and said the students tackled a difficult problem that is increasingly talked about by groups concerned about good government.

“I’m very impressed with the student participation on this and with the quality of work they’ve done,” Sharp said. “This is central to our mission. We want students to learn by doing.”