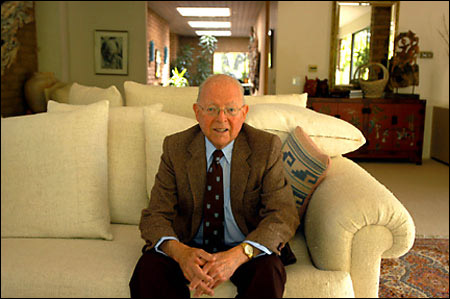

Paul F. Glenn launches labs for aging research

Five-year, $5 million commitment to HMS with goal of leveraging larger initiative

Seeking to accelerate the pace of research into the molecular mechanisms that govern aging, philanthropist Paul F. Glenn, an alumnus of Harvard Law School and founder of the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research in Santa Barbara, Calif., has committed $5 million to Harvard Medical School (HMS) over five years to launch the Paul F. Glenn Laboratories for the Biological Mechanisms of Aging. The new resources will serve as a magnet to attract additional support for the potential creation of a larger Institute for Aging Research at Harvard Medical School.

“We are proud to be teaming up with Mr. Glenn and the Glenn Foundation,” said HMS aging researcher David Sinclair, associate professor of pathology, who will direct the lab. “Like us, Paul is dedicated to finding the molecular answers to the aging process so we can understand the mechanisms of normal aging and develop interventions to delay its onset and decline, thereby extending the healthful years of human life.”

To attract talented investigators to this field and the Glenn Laboratories, a significant portion of the resources will be used to recruit two additional faculty members whose focus is aging research, and to build out the labs with advanced research technology and animal models. Additionally, research pilot grants will be awarded by a steering committee to investigators wanting to examine novel areas of molecular research addressing critical questions in the normal aging process. These pilot grants will produce data that can be used to attract larger government grants. The resources will also be used to foster collaboration by pulling together aging researchers from around the world for an annual Paul F. Glenn Symposium on the Molecular Biology of Aging to be held at Harvard Medical School.

“We structured this partnership in a way that recognizes the key drivers in the scientific process, so that the resources would be positioned to push aging research forward more quickly and to new levels of knowledge,” said Glenn.

“In pursuing the underlying molecular mechanisms involved in the aging process, the Glenn Laboratories will be supporting the broad mission of the School,” said Nancy Andrews, dean for Basic Sciences and Graduate Studies. “The School and the Glenn Laboratories research team thank Mr. Glenn and the Glenn Foundation for their leadership in this area of science.”

Research into extending life span is not new. For more than 70 years, a calorie-restricted diet has been known to increase the life span of mice and rats 40 percent by preventing them from getting diseases of aging such as cancer, heart disease, diabetes, and even cataracts. The hypothesis is that within each of our cells lies an evolutionarily ancient defense program that can be activated by so-called “longevity genes” that ameliorate the cellular damage that causes death and disease. Activation of these genes in genetically altered worms and flies has been shown to produce healthier, longer lives.

Buoyed by calorie-restriction animal tests, research teams in this small field have been pursuing the molecular pathways that mimic calorie restriction.

In the summer of 2003, Sinclair’s team showed in a paper published in Nature that a compound found in red wine called resveratrol could stimulate this pathway in yeast cells. The yeast cells lived as much as 60 percent longer, and in human cells tested in vitro, resveratrol activated a similar pathway. It enabled 30 percent of the treated human cells to survive gamma radiation, compared with 10 percent of untreated cells.

In a Nature paper published in July 2004, Sinclair’s team showed that resveratrol had a similar impact in higher organisms: worms and flies. In worms, life span was extended up to 15 percent. In flies, life span was extended up to 29 percent. Another key finding with flies was that there was no loss of fertility, which can be seen in severe calorie-restricted diets.

In a 2004 study published in the journal Science, Sinclair’s group found that a key longevity gene called SIRT1 is switched on in rats that are subjected to calorie restriction, which then increased the life span of the rat’s cells. In an interesting twist, the research team used the blood of these long-lived rats to grow human cells in the culture dish, and the human cells also lived longer, suggesting that the blood might have contained a life-giving molecule that could one day be given to people.

Although there has been much interest in the SIRT1 gene, humans actually possess seven SIRT genes, known as SIRT1-7. It is suspected that many, if not all, of these genes control aspects of the aging process. Sinclair’s group is testing whether these genes can forestall the aging process and increase the health span of mice. He has also identified a master controller of the SIRT genes, which he calls PNC1 in yeast and is called PBEF in mammals. Experiments to test whether mice that overproduce PBEF live longer, as his yeast cells did, are in progress.

Glenn’s interest in the biology of aging began as a teenager, as he observed the decline in health and death of his grandparents. While a senior at Princeton in 1951, he met Thomas Gardner, a research scientist at the pharmaceutical company Hoffman-LaRoche, who explained that aging is a complex set of biochemical processes that can be understood only at the molecular level, and that the tools of molecular biology were just beginning to be developed.

In 1965, Glenn founded the Glenn Foundation for Medical Research with a mission to extend the healthy productive human life span through research on the biological mechanisms of aging. This mission has been served through direct sponsorship of research grants and awards programs and through important relationships with other institutions focused on understanding the molecular biology of aging and mechanisms that govern the pace at which normal individuals experience physiological decline and disease.

“As we mark our 40th anniversary, we are very excited to establish this important relationship with Harvard Medical School and look forward to accelerating research into this important area,” said Mark R. Collins, president of the Glenn Foundation.

Historically, financial support for research into the biological mechanisms of aging and efforts to extend the healthy life span has been spotty. The pharmaceutical industry’s support of basic aging research is hindered due to the fact that there are no generally accepted biomarkers for aging that would allow the FDA to approve a drug designed to slow the aging process.

Although Congress supplemented scarce aging research dollars by establishing the National Institute on Aging in 1974, that money has predominately gone to disease-specific research, such as Alzheimer’s disease, or toward the behavioral aspects of aging. “Instead of addressing individual age-related diseases, we are looking at the bigger picture. Being able to extend the normal healthy life span has huge societal impact including decreasing associated health-care costs and increasing the productive life span. By understanding the basic mechanisms of aging, we hope to altogether avoid or mitigate the onset of age-related diseases as demonstrated by the research in caloric restriction,” said Glenn.

“Recent discoveries of longevity genes by Dr. Sinclair and others have persuaded me that aging includes the phenomenon of a small group of genes controlling the expression of a much larger group of genes, including those which activate cellular defense mechanisms such as DNA repair. As we learn to control expression of specific genes, we may be able to prolong healthy cell life without a complete understanding of the biochemical pathways involved.”

In addition to funding these important initiatives through the creation of the Paul F. Glenn Laboratories at Harvard Medical School, it is the hope of Glenn, the Glenn Foundation, and HMS that this initiative will serve as a catalyst for attracting new investigators and donors to support this important field of research. “We are very hopeful that during this five-year commitment we are able to build on the momentum we have generated and spur the creation of an Institute at Harvard Medical School devoted to the biology of aging, to which the Glenn Foundation has expressed possible additional support,” said Collins.