All history is local

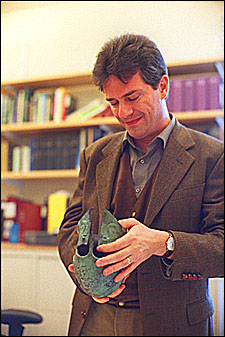

Historian Nino Luraghi studies ancient Greek texts with the eye of a literary critic

Drawing a line between areas where people use the term “hoagie” rather than “po’ boy” or “water fountain” instead of “bubbler” is the kind of problem that concerns linguists who study regional speech differences.

Historian Nino Luraghi is conducting a similar kind of research, except that his focus is not on contemporary America but on the city-states of ancient Greece.

For Luraghi, the key to these differences is the Greek alphabet, which the Greeks adapted from the writing systems of the ancient Near East. The way certain letters were formed differs markedly from one city to another, and Luraghi is convinced that these differences are not accidental, but rather reflect a deliberate effort on the part of the inhabitants of those cities to distinguish themselves from their neighbors.

“I’m arguing that the differences are intentional and that they are associated with differences in speech patterns.”

Luraghi, who was recently hired as a tenured professor in the Classics Department, believes that these differences, seen in ancient inscriptions, form patterns that clearly mark off one territory from another. The letter “beta,” for example, was written in four distinctly different ways in four cities that all bordered one another – Corinth, Argos, Sikyon, and Megara.

“The Greeks were obsessed with what made them different from non-Greeks, and in their early history, they were obsessed with what made them different from each other,” Luraghi said.

Luraghi’s study of Greek alphabetic systems is part of a larger interest in Greek self-definition, an interest that has led him to focus on how the Greeks defined ethnicity, how they governed themselves, how they distinguished truth from falsehood, and how they viewed their past.

This interest in self-definition, for example, is a significant theme in his study of the early Greek historian, Herodotus. Herodotus is the earliest historian whose work has been preserved in its entirety, a circumstance that has caused him to be viewed as the ancestor of all subsequent Western historians and to be called “the father of history.”

But as Luraghi relates in his introduction to a collection of essays he edited, “The Historian’s Craft in the Age of Herodotus” (2001), this perspective ignores a more important scholarly question – what were Herodotus’ influences and what was the context in which he produced his writings?

Luraghi is part of a recent effort to examine Herodotus in the light of oral history traditions that may have informed and influenced his work. This effort mirrors earlier work by Milman Parry and Albert Lord, who studied the verse techniques of Homer in the light of epic poems still being improvised by folk bards in the Balkans. In the case of Herodotus, Luraghi and other contemporary scholars have looked at the anthropological literature on oral historians in Africa for insights into the ways in which similar oral techniques may have influenced the early Greek historians.

“I’m interested in ancient historians as representatives of how people thought about their past and how that influenced their actions. You might call it ‘the past of the past.’”

Modern readers often find Herodotus’ account of the war between the Greeks and Persians highly entertaining because of the way he weaves anecdotes and information into his rambling narrative and reports what he is told by his informants almost in the manner of a present-day journalist. Luraghi, however, is more interested in how Herodotus reflects his own time rather than ours.

“I try to understand where the historians’ knowledge comes from, what their sources are, how they practice source criticism, how they relate to the oral tradition.”

And while he does not consider himself a literary scholar, he believes it is necessary to read historical texts with the eye of a literary critic in order to grasp the context in which a statement is intended to be understood.

“One cannot ignore the genre of any utterance, including the conversation we’re having now. It’s very important to understand what genre an utterance belongs to to understand what it means.”

For Luraghi, who was born in Turin, Italy, history is almost a family business. His father, Raimondo Luraghi, taught American history at the University of Genoa and is the author of a history of the Confederate navy that is considered one of the few important books on the Civil War originally written in Italian. Luraghi said that there was never much doubt in his mind that he would become a historian. He jokes that he chose to study the history of the ancient world because he was lazy.

“I had five years of Greek and Latin in high school with incredibly good teachers, and there was no other corner of the world I knew as much about as the ancient world. And especially if you grow up in Italy, it is very clear that the ancient world is not only a place in time, but a place in space.”

Luraghi attended the University of Venice, where he earned an M.litt. in 1987, and received a Ph.D. from the University of Rome in 1992. He was a research fellow at the University of Freiberg, Germany, and has taught at the University of Parma (1997-1999), Harvard (1999-2003), and the University of Toronto (2003-2005).

In addition to the volume on Herodotus, he is the co-editor of “Helots and their Masters in Laconia and Messenia” (2003) and the author of “Tirannidi arcaiche in Sicilia e Magna Grecia da panezio di Leontini alla caduta dei Dinomenidi” (1994), a study of early Greek tyrants. His book, “The Messenians and Their Past: Identity and Memory in the Ancient Peloponnese” (working title) is expected out soon.