African-American Pentecostalism can renew nation, says Emory’s Robert Franklin

‘Holy-rolling’ at the Divinity School

According to keynote speaker Robert Franklin, there was – even before it had ended – “a buzz already afoot nationally and internationally” about the March 18 conference on black Pentecostalism held at Harvard Divinity School (HDS).

According to keynote speaker Robert Franklin, there was – even before it had ended – “a buzz already afoot nationally and internationally” about the March 18 conference on black Pentecostalism held at Harvard Divinity School (HDS).

The groundbreaking conference, titled “Into All the World: Black Pentecostalism in Global Contexts,” was sponsored by HDS and by Harvard’s Department of African and African American Studies. About 140 participants from throughout the country engaged with 16 leading academics in the fields of history, religious studies, and sociology, who shared their expertise on three panels: “Global Pentecostalism,” “African American Pentecostalism,” and “Re-imagining Pentecostalism.”

Wallace Best, assistant professor of African American Religious Studies at HDS and co-organizer of the conference with Marla Frederick, assistant professor of African and African American Studies and of the Study of Religion at Harvard, said that what made this particular symposium unique was its aim to “bridge the artificial divide between the thinkers and the doers” and its emphasis on relating African-American Pentecostalism to the context of emerging global Pentecostalisms.

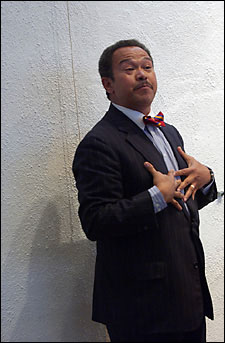

In his address, keynoter Franklin, the Presidential Distinguished Professor of Social Ethics at Emory University and an HDS graduate (M.Div. ’78), asserted that “African-American Pentecostalism has a gift to offer for the renewal of the Christian Church and for the renewal of the nation.” Pentecostalism is the fastest-growing movement within Protestant Christianity in the world. It is estimated that there are at least 550 million self-identified Pentecostals globally – and that number is expected to rise to 1 billion by the mid-21st century.

Among the contributions of the African-American Pentecostal movement Franklin mentioned was its historical influence in “re-Africanizing Black Christianity,” thereby challenging conventional mainline black churches to assert their distinctive African identities.

Franklin also pointed to the willingness of black Pentecostals to confront personal and social sin in the nation’s toughest urban centers, providing an “in-your-face ministry” that brought “Southern patterns of care and discipline into Northern cities” and provided sites of resistance against the status quo. And he added that black Pentecostals have “projected a bold Christian witness into all the world” at a time when mission work in other denominations was “falling into disrepair.”

Franklin has traveled throughout the developing world, where he has discovered that some of the major African-American Pentecostal figures in the United States (such as T.D. Jakes and Bishop G.E. Patterson) are easily accessible on satellite TV and radio. “Pentecostals own the microphone” the world over, he said, and he encouraged attendees to start thinking of Pentecostalism as a Third-World movement. “Over the past century, the center of gravity has shifted inexorably southward, with the largest Christian communities on the planet in Africa and Latin America,” Franklin noted. Earlier in the day, Hollis Professor of Divinity Harvey Cox pointed to the explosion of Pentecostal churches in China, with projected estimates of up to 50 million adherents expected by mid-century.

As Franklin touted the increasing numbers and influence of Pentecostal Christians, he also issued some clear challenges. “Pentecostals,” he said, “must engage or assist in developing new ecumenical venues” for interfaith dialogue though it will necessarily mean “risking our own comfort zone.” Pentecostals must also address the “emergence of an international underclass” brought on by ever-increasing levels of urbanization throughout the world. “That is a Pentecostal demographic. Those are our folk!” Franklin said.

To that end, Franklin called for a “Pan-Pentecostal International Youth Summit,” that would allow adult church leaders to be educated by “boys and girls from the international ‘hood, and for programs and strategies to be developed in consultation with them.”

If “the early 21st century belongs to black Pentecostals,” Franklin declared, this means that contemporary black Pentecostals must “reckon with the dilemmas and compromises that accompany our newfound visibility and influence,” and he did not pull any punches about what some of these dilemmas are now that black Pentecostals have been granted access to “the most powerful leader in the world.”

“We have holy-rolled our way up to the White House in our limo, but now that we’re there, what are we going to do with this extraordinary opportunity?” he asked.

“The work of healing the nations is not a new assignment,” he said, nor is it one that will necessarily bring personal happiness. But it is precisely this work that black Pentecostals are called to do, Franklin said.