Solving the mystery of centuries-old plagues

Wilson fingers two species in Caribbean ant plagues

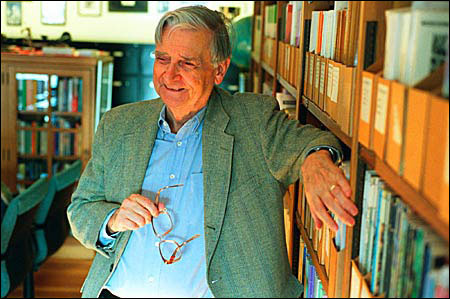

Harvard entomologist Edward O. Wilson believes he’s solved twin centuries-old mysteries of Caribbean island ant plagues that devastated local agriculture.

If Wilson is right, the episodes show that environmental problems from invasive species began just decades after Europeans came to the New World.

Wilson identified two different ant species in the plagues, a tropical fire ant in the early 1500s and an introduced African ant in the late 1700s. Both ant plagues came with widespread crop destruction that Wilson blames on the arrival of sap-sucking insects that are tended by the ants in exchange for a sweet honeydew secretion.

“This was the first recorded environmental crisis of the New World,” Wilson said. “The problem with invasive species has been as old as the appearance of the first invasive species to the New World – the Europeans. That first invasive species [Europeans] became tormented by the second [ants].”

Wilson, Pellegrino University Professor Emeritus, said he became interested in accounts of the plague ants during research on West Indian ant species that he began in the 1980s. As he became more familiar with the ant fauna of the area, particularly in the late 1990s and early 2000s, Wilson began to comb through historical material looking for clues to the plague ants’ identity.

With the help of fellow Harvard entomologist and biology Professor Brian D. Farrell, the Rockefeller Center for Latin American Studies, historians at Yale University, and material from various archives, Wilson uncovered several historical accounts of the two plagues, which occurred on several Caribbean islands from 1518 to 1519 and from 1760 to 1770.

The first occurred on Hispaniola. Wilson uncovered eyewitness accounts that described crops of oranges, pomegranates, and cassia destroyed over large parts of Hispaniola and houses invaded so often that residents took to placing their bedposts in pots of water to ward off the ants.

Those accounts described an ant with a painful bite that lived in colonies at the roots of trees. This ant was also a household pest and, though it could damage plant root systems, it didn’t cut aboveground vegetation.

Settlers of the time assumed that the crop destruction came from the ants but Wilson doesn’t believe that was the case. The ants, he said were responsible for the home invasions and the painful bites, but a second insect, unnoticed among the swarming ants, destroyed the crops.

Focusing first on the ants, Wilson said only one, the tropical fire ant with the scientific name of Solenopsis geminata, fits the bill.

“It was really a process of elimination,” Wilson said. “It pretty much had to be a fire ant and that particular fire ant.”

Turning to the second outbreak, from 1760 to 1770 in the islands of the Lesser Antilles, Wilson found accounts that described a plague no less devastating. One writer described the destruction of every sugar plantation on Barbados in the 12 miles between St. George’s and St. John’s.

Identifying the second ant culprit was a bit trickier, however, according to Wilson, as the ant described had traits similar to the earlier plague ant except one: It didn’t deliver painful bites. Though it is possible that it was again the tropical fire ant and writers of the time simply didn’t include that detail, Wilson said that is extremely unlikely, as one bitten and stung by a fire ant doesn’t soon forget the experience.

Instead, Wilson relied on descriptions of the ant and its behavior to zero in on a second suspect, the bigheaded ant, an import from Africa also known as Pheidole megacephala.

While Wilson was pretty sure of his two suspects, their identities left a big question unanswered, as neither ant destroyed crops and crop destruction was extensive. The 1500s plague on Hispaniola was described by one writer “as though fire had fallen from the sky and scorched them [plantation crops].”

The answer to that question came in the symbiosis both ant species have with sap-sucking insects, which the ants protect and care for in exchange for drops of sweet honeydew they excrete.

If a new species of sap-sucking insect arrived on the island, it could expand rapidly with its new protectors and in the absence of its native predators. This population explosion would complete the picture of the two plagues, Wilson reasoned, as a vast number of the sap-sucking invaders would not only destroy crop plants, it would also provide the ants with a new food supply, allowing their own populations to expand.

Wilson said the identity of the sap-sucking insect will remain a mystery for now, but he believes it quite possible they arrived with the first load of plantains, which were introduced to the Caribbean from the Canary Islands in 1516, just a few years before the first plague.

During those first years before the plague, the sap-sucking insects likely established themselves and began expanding their populations. During that time, they were also likely discovered and adopted by the native fire ant.

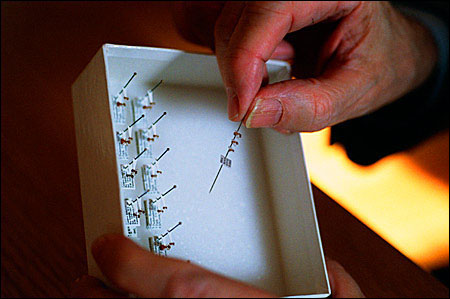

Wilson said tracking down the ant suspects in the two plagues was like taking on the role of a law enforcement officer identifying suspects in a crime.

“It unfolded like a detective story,” Wilson said.

With modern molecular and genetic techniques and ongoing archaeological efforts, it’s possible that new finds will shed more light on the case in the future, Wilson said. Wilson cited as an example a recent dig at a Roman bath in Britain that held the bodies of 2,000-year-old ants. The ant, widespread now in Europe, was an invasive species. The discovery shows that the ant was present in Britain during Roman times.

“Who knows what archival materials or artifacts dating to the 1760s or 1500s might turn up to allow a new look at this,” Wilson said. “This case may be reopened.”