Dramatist Busch teaches master class

Actor/playwright says don’t walk away from the game

For Charles Busch, author of “The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife,” the dark side of having a play on Broadway was that people would come up to him and ask how it felt to finally become mainstream.

“I didn’t realize I was ever on the fringe.”

After all, he’d been a successful writer and performer for the past 20 years. His play “Vampire Lesbians of Sodom” had run for five years at the Provincetown Playhouse in Greenwich Village. The New York Times used the phrase “camp heaven” to describe his next effort, “Psycho Beach Party,” and no less a personage than Julie Andrews called him “the subtlest and most brilliant of all drag artists I’ve ever seen.”

True, “The Allergist’s Wife” was a bit different from his earlier productions. It was the first in which an actual female performer (Linda Lavin) enacted the lead role instead of Busch himself in drag. And it was his first play to appear on Broadway (777 performances at the Ethel Barrymore Theatre). Besides, whatever doubts he may have entertained about the artistic validity of his earlier work soon evaporated as the play settled into its run.

“When that first royalty check arrived, it cured whatever was ailing me.”

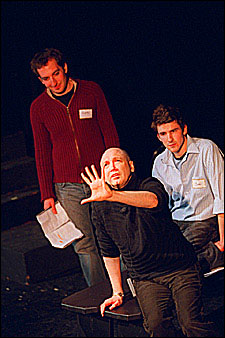

Busch was at Harvard Feb. 8 to conduct a master class with undergraduates and deliver an evening lecture titled “The Funny, Touching, Inspirational Story of My Very Eccentric Career.” His visit was sponsored by Learning From Performers, a program of the Office for the Arts.

At the master class, three groups of students acted scenes from Busch’s plays. Busch explained the origin of “Psycho Beach Party” as the students, Jojo Karlin ’05 and Scottie Thompson ’05, prepared to perform a scene from the play.

While staging skits and plays at the Limbo Lounge in New York’s East Village in the mid-1980s, Busch would give a curtain speech in which he would invent titles of works he and his colleagues planned to do in the future. “Gidget Goes Psychotic” was one that always got a laugh, and so Busch decided to actually go ahead and write it, changing the title to avoid copyright problems.

Chicklet, the young heroine, played by Busch in the original production, has all the innocence and charm of the young Sally Field, except that she suffers from multiple personality disorder (as Miss Field did in the film “Sybil”). In this scene, her mother’s refusal to give her money to buy a surfboard triggers the emergence of one of her alter egos, evil dominatrix Anne Bowman.

As Busch worked with the students, it became clear there is more to his farcical acting style than meets the eye.

“One of the characteristics of my oeuvre,” he told Thompson, who played the part of the mother, “is that you’re really playing two parts at the same time. Think of yourself as this great lady of the screen who’s a little over the hill, and now you’re in this tacky teen movie, but you’re still going to give the performance of your life. Do it like grand opera. You can’t be too big.”

A second group performed a scene from Busch’s play “Red Scare on Sunset,” a spoof on the blacklist era in Hollywood.

“Rather than do the obvious thing and make it about a poor victim of McCarthyism, I decided to turn it around and write about an actress who discovers that everyone around her is a Communist and they’re all part of a dastardly plot to destroy the Hollywood star system.”

The plot may be absurd and the speeches over-the-top, but in Busch’s world, that is no excuse for insincerity or slap-dash preparation.

“Nothing is worse in this kind of comedy than where the actor is winking at the audience, as if he’s in on the joke.”

Busch stressed the importance of research, of being thoroughly familiar with the originals that you intend to tear to shreds.

“The more specific you are, the stronger the parody. Ninety-nine percent of the audience may not have seen these films, but they know instinctively when it’s authentic.”

Sophie Kargman ’08 and Katherine Walker ’06 performed the final scene – from “The Tale of the Allergist’s Wife.” More naturalistic than Busch’s earlier work, it tells the story of a sophisticated New York matron undergoing a midlife crisis and her encounter with a childhood friend who may or may not have led the most exciting life this side of Lou Andreas-Salome.

That evening, Busch talked about his own early life and the unexpected turnings his career has taken. He said that he has been stagestruck all his life and was particularly enamored of glamorous film actresses.

“By the time I was 12, I could recite the entire filmography of Ida Lupino.”

He majored in theater at Northeastern University, but couldn’t get cast in a play. Meanwhile, he was developing his own cast of characters, many of them female, which he did mostly to entertain his roommate. After college, Busch began a career as a solo performer, creating elaborate parodies in which he played all the roles. To make ends meet, he took a variety of jobs – receptionist in a zipper factory, quick sketch artist, and a sports betting adviser. “We were all gay – aspiring ballet dancers, singers, actors, butching it up on the phone.”

Busch’s breakthrough occurred when he started appearing at the Limbo Lounge with a group of friends. “What they all had in common was that they were all unemployable.” Word spread and soon audiences were lining up around the block. Busch began to suspect he was on to something. In 1985, he and his friends raised $55,000 to stage a production of “Vampire Lesbians of Sodom,” and the rest is history.

Busch described the excitement of opening night and the emotional catharsis he experienced when he read the rave review in the Times:

“I couldn’t believe it. I went into my dressing room and just sobbed, because I knew what it meant, that I could begin to earn my living as an actor and writer.”

Since then, Busch has written a novel about his experiences in the East Village (“Whores of Lost Atlantis”), written and starred in more plays and movies, appeared on television, and played the title role in a production of “Auntie Mame.” Even his alma mater has come around to recognizing his unique talents.

“I was such a loser in college – even the gay people rejected me. And then wouldn’t you know it, about a year ago, Northwestern gave me an alumni merit award.”

And while the productions Busch has written and starred in may not be everyone’s idea of mainstream theater, the theme of his life is one everyone can identify with and aspire to.

“The artistic journey is an ongoing process of discovering who you are, and I’m still searching. You may have been dealt an odd hand, but instead of walking away from the game, keep playing. Magical things can happen.”