Stephen Prina: A man for all media

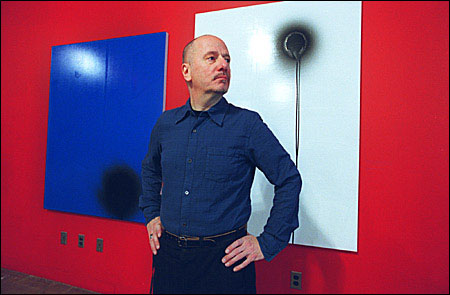

Artist tenured at VES

Stephen Prina’s artwork is full of unsuspected surprises, secret compartments that pop open to release compressed bundles of meaning or coiling strands of narrative.

In the current exhibition of his work at the Carpenter Center, for example, the piece that perhaps screams loudest for attention is a low-rider bicycle tricked out with polished chrome accessories sitting atop a baby grand piano. A friend gave Prina the bike as a going-away present when he left Los Angeles for Cambridge. The piano is there in preparation for a concert the multitalented Prina will give tomorrow (Dec. 10).

So arresting is the sight of the shiny bike where one might more commonly expect to find a bronze bust of Chopin that one is apt to gloss over the fact that, down below, the piano bench is leaning against one of the instrument’s legs. Unless you follow contemporary art very closely or unless Prina tells you, you will probably miss the fact that the leaning piano bench is actually a movement from a composition by Fluxus artist George Brecht, a piece Prina once performed.

“I like the idea of active play in artwork,” Prina said. “But it’s not about playing games. I’m not interested in riddles. It’s that some things in my work are explicit and some are implicit, and I seize on that as a form to work with. My work is always in a state of flux, always being redefined.”

Prina, an artist of international reputation whose work comprises painting, photography, sculpture, film, video, music, and performance art, was appointed to a tenured position in the Department of Visual and Environmental Studies (VES) in January 2004. He began teaching this past September.

There are plenty of examples of Prina’s implicit/explicit approach in the current exhibition. True to form, one that in its true dimensions is among the most monumental is represented in the exhibition by a pair of works that seem innocuous almost to the point of absence. A large white rectangle, covered with small numbered shapes, most of them rectangular as well, hangs beside a small framed piece of what appears at first glance to be blank paper.

The two pieces are part of an ongoing project to reconstruct the 556 extant works of Eduard Manet (1832-1883). The larger of the two pieces on display is the master document for the project, showing Manet’s works as a series of blank shapes reproduced to scale. The adjacent work is Prina’s reconstruction of one of Manet’s smallest paintings. Each of the works has exactly the same dimensions as the original to which it corresponds, but rather than reproduce the figurative content of Manet’s paintings, Prina has used a pale color wash to create a series of bland abstractions.

The question one cannot help but ask is why? Prina is not unwilling to talk about the project, but its teleological basis appears to be among the implicit aspects of the artist’s work. The key seems to be that Prina sees himself as carrying on something that Manet himself began, a way of making art based on a self-conscious relationship to the art of the past.

“Manet is often considered the first modern artist. Michel Foucault said that he was the first museum artist, meaning that Manet’s work takes as a point of departure that it is always already inscribed in the museum, that its placement within it is preordained, and Manet has rendered this condition explicit in his work.”

Stephen Prina’s exhibition, ‘Retrospection Under Duress, Reprise,’ is on display in the Carpenter Center through Jan. 7. On Friday (Dec. 10) at 11 p.m., there will be a film screening, music concert, and reception. The event is free and open to the public.

But ultimately, Prina’s intention in creating the work is unimportant. What is important, he said, is how it is received and responded to by those who experience it.

“My intention is not the meaning of the work. The work only has meaning when it enters the social sphere and meets its audience. That’s where meaning is produced, not in the studio.”

But while Prina considers the contact between work and viewer essential for the creation of meaning, his sense of play occasionally causes him to place obstacles in the way of such a meeting, obstacles that may prove insurmountable. Consider the work that at first glance seems to be a large square bench conveniently placed on one side of the exhibition to accommodate weary spectators. One may in fact sit on this object. But one may also remove the four flat cushions that cover the top to read the stenciled green lettering and learn that what appears to be a bench is actually a stack of wooden crates, each containing one of Prina’s monochrome paintings.

“The paintings have been exhibited in the past, but for this exhibition, they’re not supposed to be seen. They’re in storage, but they’re there.”

As an artist, Prina can be playful, enigmatic, even perverse, but as a teacher, the last thing he wants to do is turn out younger versions of himself.

“I wouldn’t presume to teach students my approach to making art. That would be the last thing I would ever do. It would be very irresponsible of me.”

One of the classes Prina is currently teaching is called “Lay of the Land,” which he describes as a study of “the willful assault on the vertical in Western European art,” a trend that elevated landscape painting above other genres, but that had many other implications as well. In the course, he encourages his students to work in different media, then step back and discover connections between the different works they have created.

“I try to help them give form to the many options available to them.”