Global tintinnabulation

“Bells were always special acoustic signals – they announced religious events, fire, periods of mourning, celebrations,” explains Hans Tutschku, associate professor of music and director of the Harvard University Studio for Electroacoustic Composition (HUSEAC). “For me, bells are symbols for the specific sound of a place and its culture.”

From Dec. 1 on, the cupola of Cabot House will resonate with bells from Avignon, Kyoto, or 12th century Apolda, Germany, among scores of other distant locales, depending on the hour and a selection of computer-generated bell sounds programmed into a laptop. Tutschku’s creation, “The Invisible Bell Tower,” was previously installed in Jena and Weimar, Germany; Montbéliard, France; and Florence, Italy. Each installation, says Tutschku, includes new bells he has found, bells that ring out the sounds of a tiny island in Greece to those of a bell factory in the country of Georgia.

Tutschku’s interest in aural cultural identity has informed much of his past work, which often uses collected sounds – city streets, church music, spoken poetry, and all manner of vocal and instrumental sound – as major elements in his electroacoustic compositions. He joined the Harvard composition faculty in the fall of 2004.

“Certain sounds are better for morning, some for evening,” says Tutschku as he scrolls through all the bell sounds he’s recorded, now organized into smaller “families” attributed to each hour of the day. One of Tutschku’s evening bell sounds, the so-called “Jew’s bell,” for example, was until 1790 rung in Strasbourg at 10 p.m. to warn Jews to leave the city center.

“Let’s simulate 4 o’clock. First the hour is announced by four strokes,” explains Tutschku, playing four familiar-sounding bell chimes through his computer. “This bell is followed then by one of the 4 o’clock-family bell sounds – the computer program will choose. I don’t know which one it will pick. The computer can’t repeat this bell during the next days, until it plays all the sounds inside the 4 o’clock family.”

Tutschku has been collecting bell sounds in many countries for 10 years. His oldest is from the Bell Museum in Apolda, Germany, “City of Bells,” and is an 800-year-old bell originally used to alert the town to fires. He’s also got a cathedral bell from Geneva that plays Protestant melodies, a Kyoto bell that chimes gong tones, a bell from Esztergom, Hungary, that resonates in haunting, minor chords.

“In most bells you hear the minor chords more than the major. There was a study done in Holland where they reshaped the surface of a bell to pull out the major chords to make them sound more ‘happy.’ People liked it; they found the chords so nice, joyful.”

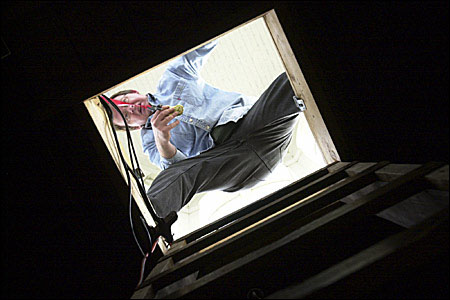

‘The Invisible Bell Tower’ can be heard through Jan. 6, on the hour, between 10 a.m. and 8 p.m. It was created by Hans Tutschku and installed by Ean White, with special thanks to Gene Ketelhohn at Cabot House.

Some of Tutschku’s bells don’t exist at all; he’s created them using architectural modeling software. “I make a grid, a physical model of the object. I calculate all the material, shape parameters, and decide how fast the hammer strikes the bell. The computer makes a simulation of it; what would happen in reality if these objects existed.”

The point, though, is not to bend the boundary between real and imaginary; all the bells sound remarkably, beautifully, real. “To me it’s interesting to see how sonic images may disturb our ordinary lives. We’re so sensitive to visual images and we are not so sensitive, we do not care so much about our sonic environment. So the bells are one way of tickling people in this direction.”