Debate over Kyoto climate treaty heats up at KSG

Putin aide declares treaty bad for environment

A top economic adviser to Russian President Vladimir Putin declared the Kyoto global warming treaty as bad for the economy, for the environment, and for public health.

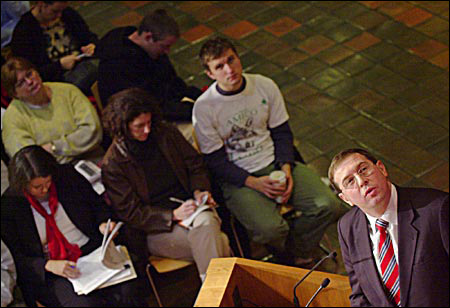

The comments were part of a debate on the Kyoto Protocol between Putin’s senior economic adviser Andrei Illarionov, Professor of Environmental Policy John Holdren, and Director of the Kennedy School’s Environmental Economics Program Robert Stavins, who is also the Albert Pratt Professor of Business and Government.

The event, “Global Warming: Is the Kyoto Treaty a Fraud?”, was sponsored by the Institute of Politics and by the Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs. Belfer Center Director and Douglas Dillon Professor of Government Graham Allison Jr. moderated the event.

Illarionov got the event started by answering the question in its title. He said Kyoto isn’t a fraud because it’s an international treaty, ratified by many nations and set to go into effect shortly. However, he minced few words in describing what he thought Kyoto was:

“I think the Kyoto Protocol is an assault on economic growth, the environment, public safety, science, and human civilization, but it’s not a fraud,” Illarionov said.

‘I think the Kyoto Protocol is an assault on economic growth, the environment, public safety, science, and human civilization, but it¹s not a fraud.’

– Andrei Illarionov,

Putin’s senior economic adviser

Illarionov’s blunt style was not reserved for the audience gathered at the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum. In his introduction, Allison said Illarionov is known for speaking his mind, even when his views diverge from those of the Russian government or of Putin himself, as they do on the Kyoto Protocol. Despite Illarionov’s opposition, Putin announced this month that Russia accepted the protocol, starting a three-month countdown for the treaty to go into effect.

In his presentation, Illarionov called the Kyoto treaty an issue of “utmost importance” to the modern world. He said the chances of Kyoto succeeding – if one assumes global warming is truly a problem – are slim, as the nations who’ve signed on represent just 30 percent of the world’s carbon dioxide emissions, 34 percent of the world’s gross domestic product, and just 13 percent of the world’s population.

“It means the Kyoto Protocol is supported by a minority of countries,” Illarionov said.

Illarionov went on to say that Kyoto’s restrictions of carbon dioxide emissions are bad for economic development. The treaty restricts production of carbon dioxide, a greenhouse gas many scientists believe is responsible for global warming. The problem, Illarionov said, is that carbon dioxide is produced through the burning of fossil fuels, which as the world’s major energy source, are needed for economic activity.

“Restrictions on CO2 emissions are incompatible with economic growth,” Illarionov said.

Illarionov said that carbon dioxide itself is not a pollutant and not directly harmful to public health or the environment, adding that focusing on carbon dioxide will detract attention from pollutants that are having an effect on the environment and, through indoor air quality, diesel fumes, and other problems, on public health.

Illarionov went on to question the science behind global warming, saying that the impact of human-caused carbon dioxide emissions on the global climate has not been proved. He cited normal variations in the sun’s strength as a major driver of the Earth’s climate and said the Earth’s temperature has a long, natural, history of rising and falling. In fact, Illarionov said, the Earth’s temperature in many places appears to be cooling, not warming.

“There is no unique global warming compared with what we’re able to observe in our recent history,” Illarionov said.

Illarionov’s assertions were immediately challenged by Holdren, who said that the vast majority of scientists knowledgeable in the appropriate fields agree that the current warming is happening and that it is linked to humankind’s burning of fossil fuels.

Holdren said scientists have examined the link between solar variation and the Earth’s temperature and have concluded that, while the sun does wax and wane in cycles, the patterns of solar variation and the Earth’s temperature don’t match. Rather, he said, they do match what would be expected by rising carbon dioxide levels generated by the burning of fossil fuels.

“The temporal and spatial patterns … match what is predicted for the observed increases in carbon dioxide and other greenhouse gases,” Holdren said.

Stavins said he agreed with Illarionov that the Kyoto pact won’t solve the most pressing environmental or public health problems, and that climate change won’t be bad everywhere.

Stavins agreed that the Kyoto treaty is a “highly flawed” approach to a global problem, saying it doesn’t include the right countries and that its restrictions come into play too fast.

“Kyoto is too little, too fast,” Stavins said.

But Stavins said that signing Kyoto was the right thing for Russia to do. After a decade of economic decline, Stavins said, Russia’s target carbon dioxide emissions in the Kyoto treaty are now higher than current Russian emissions. That will allow Russia to sell emissions credits to nations that are exceeding their quotas, netting Russia between $7 billion and $32 billion in the coming years.

By contrast, Stavins said, the United States has had rapid growth over the past decade, meaning its economy emits more carbon dioxide than treaty targets set in the early 1990s. Stavins concluded that both Russia and the United States did the right thing according to their national interests, with Russia accepting the treaty and the U.S. rejecting it.