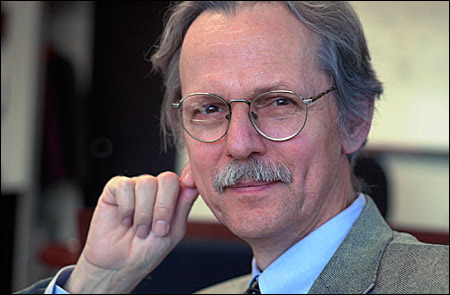

Alcock sees bright future for CfA

New director of Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics shepherds new telescope project

Charles Alcock’s history of managing large projects in astronomy will come in handy as he tackles what he said is his biggest challenge so far as the new director of the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics (CfA).

Alcock, also a newly appointed professor of astronomy, came to Harvard in August from the University of Pennsylvania, where he was Reese W. Flower Professor of Astronomy. Alcock said recently he’s still getting his bearings several months into the post.

With a staff of more than 900 spread among far-flung facilities like those on Mauna Kea in Hawaii, at Mount Hopkins in Arizona, and on Cerro Las Campanas in Chile, Alcock said it will be some time before he is able to visit all of the center’s facilities personally as he did recently with the Oak Ridge Observatory in Harvard, Mass.

And there are some instruments Alcock won’t be able to visit at all. The Center for Astrophysics also collaborates with NASA on several projects, including the Chandra X-Ray Observatory, one of NASA’s four orbiting “great observatories.”

As impressive as the center’s physical size is its scientific scope, Alcock said, with major research groups examining the cosmos in visible light, through X-rays, gamma rays, infrared waves, and radio waves.

That strength, Alcock said, creates a rich picture of the universe because researchers looking at different parts of the electromagnetic spectrum see different things.

“A lot of the richness in astronomy comes from working in multiple wavelengths,” Alcock said. “We cover a tremendous amount of ground here. It’s just a great place to get things done.”

The organization’s marriage of the Harvard College Observatory and the Smithsonian Astrophysical Observatory into the Harvard-Smithsonian Center for Astrophysics gives it an organizational complexity to match its scientific scope.

Alcock said he’s one of the few employees at the Center for Astrophysics who holds appointments in both organizations, yet he has been struck by how seamlessly people affiliated with the two separate institutions interact and work together.

One of Alcock’s first tasks will be to complete a long-range strategic plan for the institution. The planning process was started under Alcock’s predecessor, Timkin University Professor Irwin Shapiro, but Alcock asked if he could be allowed to finish it.

“I think it will be very helpful. I’ll spend three to six months getting my bearings then wrap it up,” Alcock said.

It is the large multi-institutional and multinational projects that are most dependent on long-range planning, Alcock said, as planning and fundraising for a major telescope can take 10 years or more. Such a project is in the works and Alcock said he expects it will be the single project that demands most of his attention during his tenure.

The project is a new ground-based telescope that current plans place at the Las Campanas Observatory in Chile, where the CfA collaborates on the Magellan Project’s two 6.5-meter telescopes.

Fundraising and construction have already begun for the new telescope, Alcock said. Plans call for the telescope’s 24-meter mirror to be built from seven separate 8-meter segments that have to fit together precisely in order for it to operate properly. Construction of a single mirror segment has already begun, Alcock said, which should illuminate some of the technical hurdles facing the project.

“It’s an extraordinarily challenging project,” Alcock said, “but the scientific return will be astounding.”

As complex as the project is, Alcock said he thought the center had little choice but to engage in it. The frontiers of astronomy are being pushed by such large-scale projects, funded and run by several institutional collaborators.

“The leadership in astronomy is going to people who develop the next generation of large telescopes, so not doing it is really not an option.” Alcock said.

Alcock himself is no stranger to large projects. With a doctorate in astronomy from the California Institute of Technology, he led the international MACHO project, in which scientists from seven institutions and four countries searched for large objects in cosmic dark matter. MACHO has found evidence that about 20 percent of dark matter in the Milky Way is contained in objects the size of stars. More recently, Alcock has begun looking for dark matter closer to home, in the far reaches of our solar system.

Alcock is the principal investigator of the Taiwanese-American Occultation Survey (TAOS), which he expects to be fully operational next year. TAOS will use four 50-centimeter-aperture telescopes to scan the outer solar system for small objects beyond Neptune. Finding these objects, which range from 1 to 100 kilometers in diameter, is a challenge because they’re too small to be observed directly, Alcock said.

Instead, researchers will search thousands of stars that serve as the backdrop for these objects, looking for an abrupt flicker that would indicate an object has passed between the star and Earth, momentarily blocking the light.

One of the biggest technological hurdles is the sheer volume of data coming from the project’s telescopes, which will snap pictures of thousands of stars five times per second in search for these blinks, which Alcock said would typically last just a few tenths of a second.

“The length of the blink will tell us how large the object is. The frequency of blinks will tell us how many of them there are,” Alcock said.