Modeling innovation

Throwing thrives at symposium

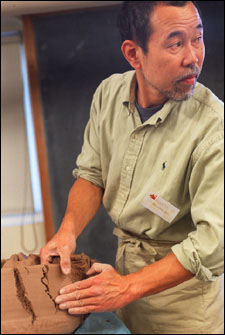

Last Friday afternoon (Nov. 5), the winds off the Charles River sent swarms of leaves swirling by the windows of the Ceramics Program Studio, while inside a group of about 30 people sat in tranquil silence. Some sketched or scribbled notes, some leaned forward, rapt, for a better look. The center of attention was Yo Akiyama – more specifically, his hands and the slab of clay he was working with as it spun on a potter’s wheel. With the nimble fingers of a masseur and a concentrated gaze, he manipulated the clay until its shape bore a vague resemblance to a lamp shade.

Last Friday afternoon (Nov. 5), the winds off the Charles River sent swarms of leaves swirling by the windows of the Ceramics Program Studio, while inside a group of about 30 people sat in tranquil silence. Some sketched or scribbled notes, some leaned forward, rapt, for a better look. The center of attention was Yo Akiyama – more specifically, his hands and the slab of clay he was working with as it spun on a potter’s wheel. With the nimble fingers of a masseur and a concentrated gaze, he manipulated the clay until its shape bore a vague resemblance to a lamp shade.

Then over the course of an hour and with the aid of a blowtorch, he stretched the cone inside out, a literal and symbolic act that signifies, as he said through a translator, finding the clay’s “true voice” or “natural characteristic” and letting it come to the surface. (To better visualize this, consider that he found inspiration for the idea when he was peeling an orange.) It’s just one of the various concepts that inform his ceramic work, which, when finished, often has a cracked-earth quality about it. With his signature style, Akiyama has established himself as a premier figure in contemporary Japanese ceramics.

Akiyama, who’s based in Kyoto, was one of three artists invited to give a master class during “Japanese Ceramics: Cultural Roots and Contemporary Expressions,” a four-day symposium held last weekend (Nov. 5-8). The event brought together artists, art historians, curators, and collectors for an array of lectures, demonstrations, conversations, and gallery tours examining how contemporary Japanese ceramicists incorporate – or rebel against – traditions.

“Americans’ understanding of Japanese ceramics is confined to a couple of categories – either folk craft or the work of people who the Japanese government has named Living National Treasures,” said Louise Cort, curator for ceramics at the Smithsonian’s Freer Gallery of Art and Arthur M. Sackler Gallery in Washington, D.C. “That aspect of Japanese ceramics tends to be conservative because the people who are rewarded are the people who perpetuate or re-create traditional processes and products, whereas the artists who are here are following different paths, reacting against that. This is a chance for people to see firsthand a broader, more accurate spectrum of what’s important in contemporary Japanese ceramics.”

The symposium was the brainchild of Nancy Selvage, director of the Ceramics Program, Office for the Arts at Harvard (OfA). This is the fifth conference in a series she developed, each of which focuses on how a particular culture expresses itself through ceramics historically and in the present. The pilot, “Ceramic Traditions of Ancient and Modern Pueblo Potters from the Southwest,” was held in 1999. After securing a grant from the National Endowment for the Arts, the Ceramics Program presented “Traditional and Contemporary Peruvian Ceramics” (2000) and “China Trade Porcelain” (2001).

“They’re designed to bring working artists together with historians and curators and to try to create an interdisciplinary atmosphere to look at work, and do so in conjunction with local museums that have great collections relevant to the themes we’re addressing,” explained Selvage. She added that despite pottery’s anthropological importance, most universities’ ceramics departments are too small to offer a specialized survey class. So she developed the series, which, probably because the resources in the area allow for a comprehensive approach to the topic, draws an international crowd.

“To connect contemporary expression with historical expertise and research in one environment is unusual,” said Cathy McCormick, director of programs at the OfA.

More than 130 participants were treated to the opportunity to watch some of the world’s foremost Japanese ceramic artists at work, attend lectures, and see the art on display in public spaces in art bastions like the Boston Museum of Fine Arts and Harvard’s Arthur M. Sackler and Peabody museums, as well as more intimate spaces like Judith Dowling Asian Art on Charles Street. Curators or art historians served as guides through each collection.

“What [the symposium] is doing is so important, and it impacts the entire ceramic community,” said Anita Sherwood, director of the Pucker Gallery on Newbury Street, one of the stops on a circuit of local galleries on Friday night. “Many artists have gone to Japan and had that cross-cultural experience. The conference seems to show the transition from traditional to contemporary, which is critical for seeing that a thread runs through.”

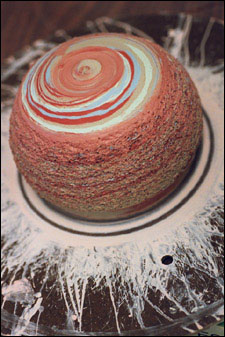

Other master artists included Ryuichi Kakurezaki and Makoto Yabe, who teaches at the School of the Museum of Fine Arts. That contemporary ceramicists are not rigidly constrained by tradition becomes very clear when you look at their work side by side. Each artist’s oeuvre focuses on a different aspect of the clay.

“Akiyama-san deals with the physical nature of the material, [Kakurezaki] exploits the physical properties of clay and how it interacts with the firing process, and Yabe-san deals with more of the painterly, surface treatment,” Selvage elucidated.

How do the artists feel about representing new directions in Japanese ceramics?

Speaking through a translator, Akiyama, a wiry man with muscular fingers and a salt-and-pepper beard, said he doesn’t want to be stuck in any definition of tradition. Rather than offering some grandiose explanation, he said tradition is only understood through personal experience. The symposium, he added, was a great opportunity for him to learn something about himself and where he fits in.