HEMS will perform ‘first great opera’

Kelly and company stage production of theatrical piece ‘L’Orfeo’

In 1607, about a year after Shakespeare’s “Macbeth” premiered in London, poet Alessandro Striggio and composer Claudio Monteverdi presented a new play at the court of Mantua in Italy.

The play, titled “L’Orfeo,” was something of a novelty. Instead of speaking their lines, the actors sang them, accompanied by a splendid array of instruments. Even in an age when audiences expected every play – including tragedies – to contain a few songs and dances, the sheer volume of music in this production must have seemed overwhelming.

What audiences only came to realize afterward was that “L’Orfeo” was a new species of entertainment, a marriage of drama and music that eventually took the name opera. Although it had only two performances, the work would inaugurate an enduring musical genre encompassing “Don Giovanni,” “Parsifal,” “Aida,” “Madama Butterfly,” “Porgy and Bess,” and “Einstein on the Beach.”

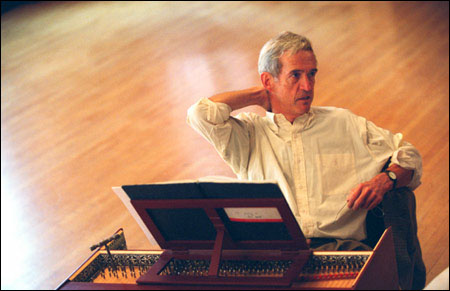

“‘L’Orfeo’ wasn’t the first opera,” said Thomas Kelly, the Morton B. Knafel Professor of Music. “There were a few experiments in Florence earlier in the century that Monteverdi probably knew about, but it was the first great opera.”

Kelly ought to know. He has been teaching the opera for 10 years in his core course “First Nights: Five Performance Premieres,” in which students examine five famous pieces of music, both as timeless works of art and as moments in cultural history. In 2000, Kelly published a book based on the course. He has also directed three different productions of the opera and is now hard at work on a fourth.

The new production is by the Harvard Early Music Society (HEMS), a student organization dedicated to performing music written before the 19th century with attention to historical performance practice. It was HEMS that recruited Kelly to direct this new “L’Orfeo” production.

“They came to me because they knew I love the piece so much.”

As chair of the Music Department, Kelly finds that administrative duties now take up much of his time, and yet he did not hesitate to accept the students’ request.

“I jumped at the opportunity. It’s taking a lot of my time, but I’m enjoying every minute of it. This has nothing to do with self-sacrifice. It has to do with selfishly wanting to be near the music you love.”

Kelly believes that “L’Orfeo,” like many of Shakespeare’s works, still captivates audiences because it deals with a basic human struggle, although it does so in mythological terms.

“It’s about a predicament we all find ourselves in, the conflict between the head and the heart.”

The opera tells the story of Orpheus, the world’s greatest singer, and his attempt to retrieve his wife Eurydice from Hades, the realm of the dead. Moved by Orpheus’ plaintive song, Pluto, the god of the underworld, gave Eurydice her life back, but only if Orpheus could lead her out of Hades without looking back. At the last moment he gave way to his desire to see her and lost her forever.

“His head tells him, don’t look back, but his heart says, I love her – how do I know she’s still there?”

But while the theme of the opera may be familiar, the instruments that audiences will see and hear in this performance are apt to be less so.

Most audience members will recognize the delicate harpsichord, but will they know the regal, an Italian organ with reeds similar to those in a harmonica whose sound seemed to Monteverdi to be just right for accompanying sinister figures of the underworld? Then there are the sackbuts, ancestors of the trombone but with a narrower bore, which makes them difficult to master for musicians trained on modern instruments.

“Trombonists go crazy when they first deal with them,” Kelly said. “It’s like driving a sports car rather than a Cadillac.”

Listen particularly for the cornettos, curved conical horns with finger holes and tiny trumpetlike mouthpieces, whose sound one 17th century writer compared to “a ray of sunshine in a darkened cathedral.”

Another group of brass instrument to listen for is the natural trumpets, hunting horn-like instruments without keys or valves that play only a harmonic series of notes like a bugle, but in a higher register. They are generally used for fanfares.

Performances of ‘L’Orfeo’ will take place Thu., Nov. 18-Sat., Nov. 20 in the Horner Room of Agassiz House at 8 p.m. Tickets are $20 general; $9 students and are available through the Harvard Box Office (617) 496-2222.

More on ‘L’Orfeo,’ plus a taste of the music

Violins, violas, and cellos will also be heard, but they will sound a little different from those in a modern orchestra because they will be fitted with gut strings (rather than the wire and synthetic ones used today) and will be played with lighter baroque bows.

As a further gesture toward authenticity, the opera will be presented in the Horner room in Agassiz House, an elegant neoclassical parlor that Kelly describes as “the closest approximation to a grand room in a palace.” The room is somewhat limited in size, but then so was the room in the palace at Mantua where the opera was first presented. The only difference will be that while one had to be a personal friend of the duke to see the 1607 performance, all that is necessary to get into the 2004 version is to purchase tickets at the Harvard Box Office.

Would Monteverdi find the new production to his liking? Kelly believes he would.

“I think Monteverdi would be surprised and I hope delighted that we still love ‘L’Orfeo’ so much.”