Voyage to the bottom of the sea

Charles Langmuir leads deep expedition

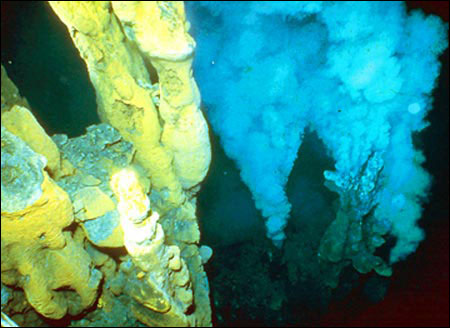

Far below the Pacific Ocean’s waves, seabed vents spew hot water, minerals, and nutrients into the cold, dark depths, opening a window to the geologic processes driving them and anchoring biological communities that scientists hope can reveal the secrets of life’s beginnings.

A team of international scientists is searching for undiscovered ocean vents off the island kingdom of Tonga, in the Pacific Ocean north of New Zealand. The cruise’s ambitious scientific effort is headed by Professor of Geochemistry Charles Langmuir, who is serving as chief scientist.

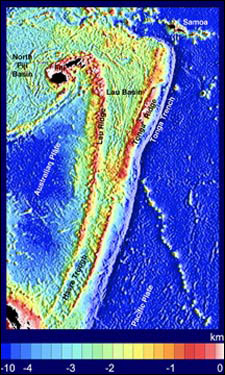

It is the second in a five-cruise effort called South Pacific Odyssey, whose aim is to discover, map, and explore the unique ocean floor vents in a part of the Pacific Ocean called the Lau Basin.

The Lau Basin is a V-shaped bowl between two undersea mountain chains whose tops poke through the ocean surface to form the islands of Tonga and Fiji. The area is unique because it is a site of intense volcanic activity and of two different types of interactions between the Earth’s surface plates: One forces the crust downward as two plates collide and the second sends molten crust material to the surface as plates move apart.

These unique characteristics give scientists a chance not only to explore the biological communities that surround these hot water vents, but also to deepen their understanding of the Earth’s continental plates and their effect on the surrounding environment.

“We are exploring and discovering new things every day, mapping terrain not mapped before, collecting samples from regions never sampled before, finding vents that we believe to be there but have never been seen by human eyes,” Langmuir said in a recent e-mail from the research ship, R/V Kilo Moana. “Each day is discovery and adventure.”

The cruise has two main goals. The first is to find at least two new ocean floor vents in different areas. The second is to collect samples of the volcanic rocks that make up the region’s sea floor.

The chemical composition of the Earth’s crust in the area changes steadily from north to south. Both the cruise’s rock sampling and vent discovery programs are designed to use that chemical change to better understand ocean ridge volcanoes and their associated vents.

Researchers have already recovered rock samples that they hope will illustrate those changes and have identified four new hot water vents in different areas that later cruises will more closely study for physical differences and differences in the biological communities they support.

“Our cruise sets up the … following cruises, by finding the specific vents for them to investigate in detail,” Langmuir said. “The last cruise consists almost entirely of biologists, and they in particular are depending on us to find the vents so they can study the animals.”

Hydrothermal vents were first discovered as sources of deep-sea life in 1977 when the U.S. submersible Alvin found a community of unknown creatures, such as giant tube worms, clustered around undersea vents in the volcanic Galapagos Rift.

Living in the ocean’s depths, the creatures survived in the pitch black far below the surface. Scientists quickly understood that these communities were very different from life elsewhere, much of which relies on the ability of plants and bacteria to capture energy from the sun’s rays through photosynthesis.

Around the deep-sea vents, life is based on its ability to use energy from chemicals expelled from the vents in a manner similar to the way some believe life first arose on Earth.

The South Sea Odyssey cruise program is part of a larger program called Ridge 2000, headquartered at Pennsylvania State University and dedicated to exploring ocean floor spreading centers, where the Earth’s crust splits apart, allowing lava to push up from the mantle.

The cruise, scheduled to return to Fiji Oct. 17, got off to a difficult start, with the early loss of two rock-sampling tools, which are towed behind the ship in the mile-and-a-half-deep water to retrieve rocks from the ocean floor. The second major setback occurred before the Kilo Moana left port, as a shipping mishap meant chemical sensors intended to help locate vents on the floor never arrived.

Despite these setbacks, Langmuir said they had made significant progress.

By the cruise’s midpoint, the scientific team had used backup rock dredges to collect rock samples from 100 locations. The team also found four new hydrothermal vents, marking the first time so many vents have been located over a large region in a single cruise.

Langmuir, a veteran of 20 deep-sea expeditions over two decades, said the discovery of new vents, though important, is also quite difficult. While their educated guesses as to vent location can help narrow the 200-mile long search area to a few square miles, the vents themselves are just a few meters across and can be difficult to pinpoint.

Researchers take advantage of advanced technology in the form of an underwater vehicle called Autonomous Benthic Explorer (ABE) to find the vents. ABE crisscrosses the search area at about 250 meters above the bottom, searching for plumes of warm water and suspended particles coming from the vents.

Once a plume is detected, ABE repeats the search, closer to the bottom, at 50 meters, until it again hits the plume, presumably right over the vent this time. Once discovered, the vehicle moves in closer, to 10 meters, taking pictures of the bottom and the vent itself.

Though it sounds straightforward, Langmuir said shifting ocean currents and tides can make the plume locations change from day to day.

“They move up and down with the tides, and they slosh around over many miles of the sea floor. We have found that their depth one day is different from their depth on another, and that a big signal at a particular spot can be missing from one day to the next,” Langmuir said.

Langmuir likened the plume-tracking activity to finding a polluting building by tracking a smokestack plume from an airplane overhead on a cloudy day. He said the team misses the chemical sensors, which would have told researchers how close a located plume is to a vent site.

In addition to its use of ABE, Langmuir said the cruise benefited from the arrival of a Japanese team, with the submersible Shinkai 6500, at the research site. The Japanese team took detailed maps of possible vent locations from the South Pacific Odyssey team and confirmed the existence of a large new vent field in the southern region.

“It is a privilege to be at sea with such advanced technology and such a great team of people,” Langmuir said.