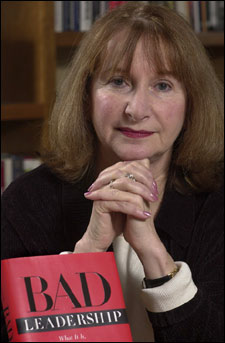

Kellerman describes, decries ‘bad leadership’

Scholar looks at the corrupt, incompetent, and just plain bad at the top

“Attention must be paid.”

The words, originally spoken in Arthur Miller’s classic play “Death of a Salesman,” resonate with Barbara Kellerman, research director of the John F. Kennedy School of Government’s Center for Public Leadership.

Attention, Kellerman said recently, must be paid to the bad leadership exhibited all too often by people at the top of political, corporate, and even nonprofit organizations.

In short, Kellerman says, bad leadership is all around us, which is what makes it so puzzling that so little has been written about it.

In her recent book, “Bad Leadership: What It Is, How It Happens, Why It Matters,” Kellerman examines the traits that mark bad leadership, categorizes them, and offers clear examples that range from Saddam Hussein’s evil regime to Bill Clinton’s neglect of the Rwandan genocide to Mary Meeker’s stubborn adherence to favored stocks even as the markets tanked, to former Washington, D.C., Mayor Marion Barry’s well-known addictions.

“People are not idiots,” Kellerman said. “People know that bad leadership happens, and often, and that it has a significant and inevitably deleterious impact on their lives.”

Despite that reality, Kellerman said her work is designed to fill a void created by the meager amount of research and scholarship on bad leadership. Though there have been many works written about leadership and how to improve it, they have largely focused on good leadership and how to be a better leader.

“A leader is usually thought of as someone with vision and integrity and a range of other traits typically associated with being a paragon of virtue,” Kellerman said.

But Kellerman argues that leadership isn’t just about making the world a better place. Some leaders, such as Adolph Hitler, to cite an extreme example, may have evil aims, but can also be remarkably effective. Between 1933 and 1941, Hitler had many striking successes that not only transformed Nazi Germany, but also changed the map of Europe.

Kellerman said the American focus on good leadership is attributable to many reasons, not least among them an innate optimism. Clearly many Americans believe that they can learn how to be a good leader – evidenced by the thousands of available how-to books – just as they can learn to do almost anything on which they set their minds.

In her book, Kellerman points out that bad leadership can be either ineffective or unethical or both. She further delineates and describes seven different types of bad leadership: incompetent, rigid, intemperate, callous, corrupt, insular, and evil.

Kellerman discusses characteristics of each type of bad leadership and offers real-world examples, drawing from various different spheres of society, different countries, and different cultures. Among them are the former head of the International Olympic Committee Juan Antonio Samaranch; the former head of Sunbeam, Al Dunlap; and the former head of The United Way of America, William Anthony.

Kellerman said that Americans have been fortunate in their political leadership. Unlike most of the rest of the world, the United States has generally been spared the despotic leadership evidenced in so many other countries.

Kellerman takes care to separate the leadership from the leader, saying that leadership is best understood by focusing on three variables: the leader, the followers, and the context of the times.

With the book coming out in the midst of an election season – it was published in September – Kellerman has fielded many phone calls from media outlets wanting to talk about leadership. She has obliged, but declines to characterize the leadership of either President George Bush or challenger U.S. Sen. John Kerry as “bad.”

Kellerman said she wants to spur scholarship and discussion on the topic of bad leadership and weighing in on the presidential race would merely politicize her work and make it appear partisan.

While Kellerman examines many leaders in considerable depth, she doesn’t let the rest of us completely off the hook. Without followers, after all, leaders could not lead badly.

“Followers are every bit as important to leadership as are leaders,” Kellerman said. “You can’t have bad leadership without having bad leaders and bad followers.”

At the end of the book, Kellerman offers a bit of advice to both leaders and followers on how to stop or slow bad leadership. Kellerman urges followers to do more and to speak up when bad things start to happen.

“Be emboldened to act. Consider it your right, your duty to take a stand,” Kellerman said. “If we tolerate bad leadership, we will get the leadership we deserve.”

As for the leaders, Kellerman does have some sympathy. In her studies of leadership over the past few decades, Kellerman said it has struck her how extremely busy leaders really are as they juggle many competing demands on their time. She believes it is at least in part due to the fast pace of their lives that leaders lose the ideals and aspirations that inspired them to want to create change in the first place.

Consequently, for leaders, Kellerman recommended self-reflection and, just in case, term limits.

“Leaders who stay in power for too many years tend over time to perform less well,” Kellerman said. “So be prepared to give it up and get out.”