Widener Library renovations: On time, on budget

Lovingly renovated Widener prepares for 21st century scholars

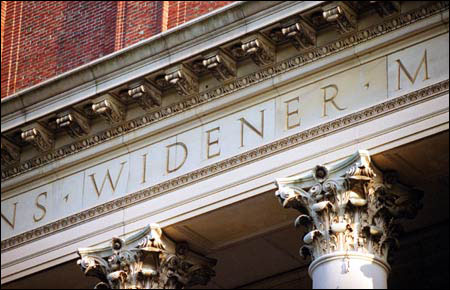

For the past five years, Widener Memorial Library – one of Harvard’s best-known buildings and the heart of its 90-library system – has surrendered its scholarly serenity to the cacophony of construction.

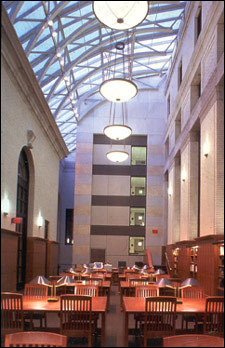

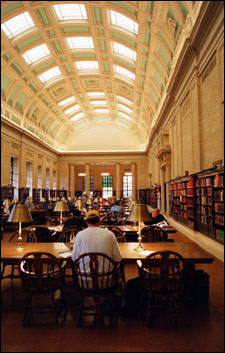

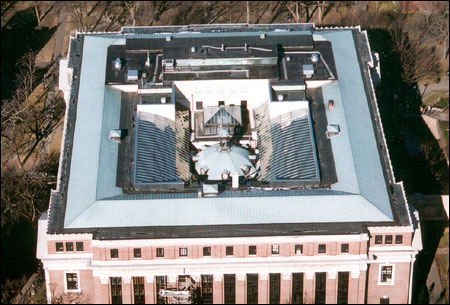

Abiding by Mrs. Widener’s mandate not to change the ‘footprint’ of the building, a glass roof installed over former light corridors (below) allowed the library to add new space, including the Phillips Reading Room (above, left). The Loker Reading Room (above, right) was restored to its original architectural glory.

Abiding by Mrs. Widener’s mandate not to change the ‘footprint’ of the building, a glass roof installed over former light corridors (below) allowed the library to add new space, including the Phillips Reading Room (above, left). The Loker Reading Room (above, right) was restored to its original architectural glory.

Its stately steps and brick façade disappeared beneath scaffolding and plywood; its walls were gutted and threaded-through with up-to-date plumbing, climate control, and electrical and data conduits; its long-suffering staff was shuffled through nearly 500 temporary workspaces. Bowls of earplugs greeted patrons during noisy phases of construction, and the landscape of Widener’s 10 stories of stacks changed so often that the call number location chart was reprinted 65 times. Every single book in the library’s collection – 3.5 million of them – was moved, cleaned, and reshelved.

Yet from the start of Widener’s two-phase renovation in 1999 to its finish this past July, the library remained open for business. Perhaps even more stunning, the $90 million-plus project concluded on time and on budget.

“This was a group that worked as a team,” says Nancy Cline, the Roy E. Larsen

Tomorrow (Oct. 1), President Lawrence H. Summers and Dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences William C. Kirby will join Nancy M. Cline, the Roy E. Larsen Librarian of Harvard College, to officially rededicate the renovated Widener Memorial Library. The ribbon-cutting ceremony, open to the entire University community, begins at 1:30 p.m. on the steps of Widener Library, followed by a reception in Tercentenary Theatre.

Librarian of Harvard College, heaping praise on the two committees that drove the project – a planning committee of University administrators and professors, and a building committee of librarians, facilities experts, and representatives from contractor Lee Kennedy Co. and architects and engineers Einhorn Yaffee Prescott. “Everyone was working with shared objectives,” she says.

Those objectives, says Cline, have resulted in a library that’s as relevant and user-friendly for the 21st century scholar as it was for scholars at the beginning of the 20th.

“Outwardly, Widener looks much as it did nearly a century ago. Inwardly, its dramatic changes will benefit the health and security of our collections but also the learning life of the Harvard community,” says William C. Kirby, dean of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and Edith and Benjamin Geisinger Professor of History. “That so much activity has taken place, these five years, behind that tranquil facade, suggests a capacity to grow with the times that I find very heartening.”

Preserving Widener’s treasures

While library patrons surely first notice Widener’s gleaming marble, handsome and functional new reading rooms, or wireless technology, the renovation was sparked by the far less sexy but more pressing need to preserve the library’s collections. In 1915, state-of-the-art library construction called for lots of air and light; by the end of the 20th century, preservationists knew that they were public enemies one and two for the long-term safety of old books.

“The absolutely priceless and irreplaceable collections were simply cooking and subject to some of the worst environmental conditions imaginable for something of that value,” says Cline.

The renovation’s Phase One replaced HVAC systems to maintain a books-friendly 68-degree, humidity-controlled climate in the stacks; statistics show that these and other upgrades could double the lifespan of the collection.

In the process, the stacks became friendlier places for the humans who work and study in them. Upgraded lighting, fire suppression, and security systems make the stacks safer, while larger study carrels, with data jacks and wireless access, better accommodate 21st century scholars.

Phase One also saw the addition of space – two reading rooms as well as staff space – in a building famously constrained by the donor’s mandate that its footprint never be altered. The family of Eleanor Elkins Widener did, however, approve the glass-roofed enclosing of the library’s two light courts, which created the bright new Phillips and Stacks Reading Rooms.

Still relevant after all these years

If the first phase of the Widener renovation created new space and extended the

Widener Library renovation project facts & figures

- Moved 474,470 items (13,500 boxes) during the HD Push project

- Erected a 180′ crane with a 300′ boom

- Lifted 191 tons of steel into the lightcourts

- Removed 92 tons of demolition debris from D-Level

- Installed 7 miles of toe kick molding on bottom of each stack range

- Applied 2,000 gallons of paint

- Installed 13 miles of HVAC sheet metal ducts throughout building

- Placed 5 miles of sprinkler piping

- Installed 5,000 sprinkler heads

- Installed 55 miles of electrical cable, 15 miles of fire alarm cable, 18 miles of electrical conduit, and 11 miles of tel/data cable

- Filled 600 dumpsters equal to 3,600 tons of debris

- Relocated approximately 9 miles of tel/data cables

- Removed 1,200 cubic yards of soil (249,600 gallons) from lightcourts

- Poured 777 yards of concrete delivered in 90 truckloads

- Removed 151 tons of ductwork and cast iron debris from penthouse/attic

- Replaced 4,000 light fixtures and 1,000 switches in the stacks

- Installed 1.5 miles of new HVAC ductwork, 1 mile of sprinkler piping, and 5 miles of electrical wiring in the attic

- Placed 175 new registers in the ceiling of the Third Floor

- Removed and cleaned over 8,000 shelves and 4,800 bookends

- Removed, cleaned, and reshelved 3.5 million books

- Moved 160,000 reels of microfilm to the new reading room

- Rewrote and printed 65 versions of the Call Number Location Chart

- Attached nearly 8,000 brass range number tags to steel stack ends

- Installed more than 900 tel/data outlets

- Relocated over 1,000 wall hangings, including artwork, clocks, and bulletin boards

- Cleaned, refinished, and sealed 120,000 square feet of marble flooring

- Installed close to 6,000 light fixtures and 3,000 switches on floors D – 3

- Recycled and refinished 560 library chairs

- Set up and broke down 478 temporary work stations

- Moved almost every staff member and her/his work area at least two times

- Kept the library open throughout the project

lifespan of the collections into the future, Phase Two focused, in many ways, on peeling away the past. In an effort to return the library’s once-public spaces back to its users, the renovation disassembled rabbit warrens of staff cubicles and replaced shelving and storage with armchairs and HOLLIS terminals.

“We had encroached in many ways in just about every imaginable corner to make way for staff, for a whole host of processing activities,” says Cline. “When we started to take it all apart, it really became clear we could do a much better job of aligning things in the building.”

Such better alignment has not only produced additional space for users, including the lovingly restored Loker Reading Room, but also a far more sensible arrangement of collections, staff, and purposes. Reference activities, which tend to be noisy and interactive, are now in a room beside Loker, which fosters quiet contemplation and study. Staff are clustered in spaces that are functionally aligned, and collections previously scattered throughout the library are now contiguous.

A happy by-product of this public-facing phase of the renovation is that business is booming. Undergraduate usage of the library and its collections is up 181 percent since 1990; borrowing rates by graduate students rose 245 percent in that same time period.

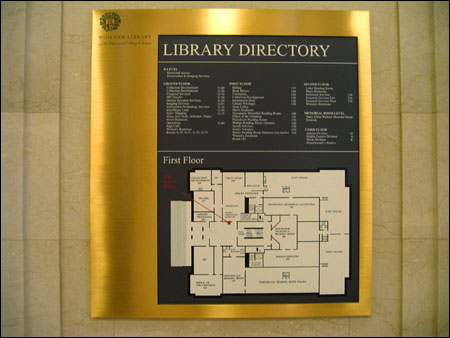

Cline attributes these increases to factors both concrete and conceptual. As the renovation progressed, the library became a more pleasant place to work and an easier place to negotiate. Once devoid of maps or signs – “There was the expectation that if you were good enough to qualify to get into the stacks you certainly didn’t need any help,” says Cline – the new Widener now boasts directionals at every turn. And by restoring some of the building’s most public spaces to their original architectural glory, the renovation has brought patrons to once-dingy spaces.

“The whole building feels much lighter and open and accommodating to inquiry and scholarship,” says Cline.

Even more, she says, Widener’s increasing usage points to the enduring relevance of libraries, which some predicted would become obsolete with digital technology. Rather, says Cline, new technology and old are merging together and Widener’s vast resources – from its collections to the librarians who help scholars navigate them – are constantly reinventing the way knowledge is accessed.

“The value of the library exists for different reasons than it may have 85 years ago. We have tried to make Widener not only ready for today, but as flexible as possible, to grow and change as technology and the methods of information production change in the future,” says Cline. “The library as place is absolutely important here in the life of the mind.”