Scalia condemns judicial moralism

Scalia: Morality should be determined by society, not judges

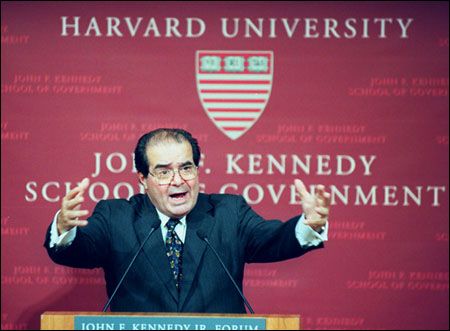

U.S. Supreme Court Justice Antonin Scalia told a packed John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum Tuesday night (Sept. 28) that democracy is best served when judges stick to determining the letter of the law and refrain from ruling on moral issues such as abortion and assisted suicide.

Scalia, appointed in 1986 by President Ronald Reagan, decried the current trend toward activist judges, saying that because morality changes with society and is viewed differently within different segments of society, it is dangerous for judges to create absolute rights and wrongs.

“These and many similar questions [like abortion and assisted suicide] involve basic human rights and surely there are right and wrong answers to these … but my answers are not the same as yours,” Scalia said.

Scalia, a graduate of Harvard Law School, delivered the 2004 Edwin L. Godkin Lecture at the Kennedy School. He was introduced by Kennedy School Dean David Ellwood, who hailed Scalia’s intelligence and “rapierlike wit.”

Scalia drew an analogy to today’s penchant for judicial activism to the past fascination with technical experts that resulted in the creation of numerous independent regulatory agencies, such as the now-defunct Interstate Commerce Commission and the Federal Communications Commission. These agencies, Scalia said, were created to insulate them from politics with the belief that regulatory questions could best be answered by impartial experts.

What the nation found in practice, Scalia said, was that the system failed because many of the questions these agencies wrestled with were tied up in societal values – such as the importance of quality television programming – and thus best addressed through the political system.

Though the lesson of the past was that it’s “utterly impossible to take the politics out of government,” Scalia said, the public’s enchantment with experts has been replaced with an enthusiasm for judicial moralists. Over the last half-century, Scalia said, judges are ruling increasingly on intrinsically moral issues, such as abortion, assisted suicide, same-sex marriage and the death penalty, all issues whose resolution are best left to society through democratic processes.

“What I am questioning is the propriety, indeed the sanity, of having value laden decisions such as these made for the entire society – and in the case of Europe for a number of different societies – by judges,” Scalia said. “Nothing I learned from law courses here at Harvard, none of the experiences I acquired in practicing law, qualifies me to decide whether there ought to be a fundamental right to abortion or assisted suicide.

“Just as it proved impossible to take politics out of economic regulation, so it will prove impossible to take politics out of the year by year refashioning of society’s official views on human rights.”

During a question-and-answer period following the talk, Scalia answered questions posed by Harvard students on several controversial topics. He defended his decision not to recuse himself from a case involving Vice President Dick Cheney shortly after going on a hunting trip with the vice president. Scalia said that since Cheney was involved in the case solely due to his position as vice president that it was appropriate for Scalia to sit on the case. He also defended the Supreme Court’s action in the 2000 presidential election, saying the court was not engaging in undue activism, rather it was doing its job, ruling on an issue of critical national importance that otherwise would have been left to the Florida Supreme Court to decide.

In response to a question about how far he would let political majorities decide moral issues, Scalia said that too, is up to the majority to decide.

“I have no objection to restricting the majority, so long as the majority itself has identified those restrictions,” Scalia said. “I believe in liberal democracy, which is a democracy that worries about the tyranny of the majority, but it’s the majority itself that must draw the line.”