East Asian painters have powerful impact

Compelling legacy on view at Sackler Museum

To someone accustomed to Western art with its vivid colors, its emphasis on the human figure, its use of naturalistic modeling and perspective, East Asian painting may seem a bit pallid at first – pretty enough with its graceful calligraphic lines and its ever-present repertoire of bamboo, plum blossoms, and chrysanthemums, but somehow lacking in individuality and oomph.

While a painting by a Chinese, Japanese, or Korean artist is unlikely to produce in a Western observer the same impressions and sensations as a portrait by Rembrandt, Titian, or van Gogh, this is not to say that, once certain basic cultural and aesthetic differences have been taken into account, East Asian painting cannot have an impact that is equally powerful.

Take the painting “The Guardian of the Valley” by the 14th century Chinese artist Li Shixing, now on display in the exhibition “A Compelling Legacy:

Masterworks of East Asian Painting” in the Sackler Museum. Painted in black ink on silk, the painting depicts an ancient leafless tree against a misty, watery landscape.

The untutored eye can readily appreciate the majesty and expressive quality of the old tree’s gnarled form, as well as the grace and sensitivity of the brushwork, but it also helps to understand the image as a manifestation of the ancient Chinese philosophy Taoism.

“There was a taste for showing trees in winter, in their leafless state, because of the Taoist search for characteristics that underlie the harmony and unity of the universe,” said Robert Mowry, the Alan J. Dworsky Curator of Chinese Art. “They tended to look at the parts of nature that were unchanging and constant, rather than trying to capture fleeting moments as many Western artists do.”

Taoism informs East Asian landscape painting in another way. Virtually all these paintings show in some way the juxtaposition of mountains and water. In fact, the Chinese word for landscape, “shanshui,” means “mountains and water.” The downward flowing water and the upward thrusting mountains represent yin and yang, the two basic forces underlying the structure of the world.

There are few places in America – in fact, few in the world – that offer the opportunity for contemplating Asian art as the Sackler does. There are about 18,000 individual items in the collection, many of them world-class. Harvard’s

‘A Compelling Legacy: Masterworks of East Asian Painting’ is at the Sackler Museum through March 20, 2005. Visit http://www.artmuseums.harvard.edu

for more information.

collections of archaic Chinese carved jade and of Japanese surimono woodblock prints, for example, are considered the world’s finest, and more recently, the museum has acquired collections of Korean art that surpass those of most other institutions.

For the Sackler’s current exhibition, Mowry has brought out the museum’s most honored masterpieces. Those with an interest in Asian art or in learning about Asian art owe it to themselves to go over and take a look.

The stories of how some of these pieces were acquired are fascinating. “The Guardian of the Valley,” for example, is part of the Edward B. Bruce Collection, which came to Harvard in 1923. Bruce was a lawyer who practiced in New York and Manila. During business trips to China, he became fascinated by Chinese painting and amassed a large collection. In 1923, he sold his collection to Galen L. Stone, Boston banker and philanthropist, who gave it to the Fogg Museum. The sale enabled Bruce to give up law and devote himself to his own painting career.

Bruce was one of the first Westerners to collect what is known as literati paintings, works by highly accomplished amateurs who combined the skills of painters, poets, and calligraphers. Their styles tended to be looser and more expressionistic than those of professional painters, whose works were marked by greater naturalism. Until the advent of modernism, most Westerners regarded the work of the literati as decadent and artistically worthless. Bruce, who had gotten to know Chinese collectors and connoisseurs and learned from them, was able to see past this Western prejudice.

Philip Hofer ’21, formerly the curator of printing and graphic arts at Houghton Library, was another important collector of East Asian art, whose donation of more than 700 items greatly enriched the Sackler’s holdings. Among the many works he gave to Harvard was an album of paintings and calligraphic excerpts from “The Tale of Genji,” the 11th century Japanese literary masterwork that many consider to be the world’s first novel.

The paintings were originally thought to date to the 17th or 18th century, but on the basis of careful study, they are now known to have been produced in the

early 16th century and, in fact, to be the earliest complete set of album-leaf format illustrations of the novel now in existence. Moreover, the paintings have been identified as the work of Tosa Mitsunobu, founder of the important Tosa School.

“Usually when we make a discovery about the authorship of a work, its value is revised downward. It’s only once in a lifetime that one has the pleasure of seeing a work rise to the masterpiece level,” Mowry said.

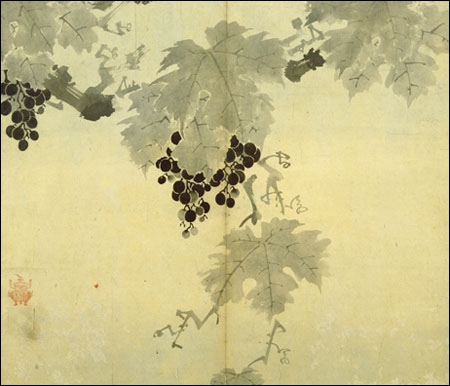

The stars of the show, however, are the Korean paintings. Since Harvard acquired a group of 30 Korean paintings in 1994 – a purchase that included two 17th century paintings of fruiting grapevines currently on display – Mowry has concentrated on enlarging the collection. The museum now has about 150 Korean paintings to match its first-rate collection of Korean Buddhist sculptures and its superb collection of Korean ceramics acquired from Mrs. Gregory Henderson in 1991.

Among the Korean paintings acquired over the past decade are several spectacular pieces now on view. They include the six-panel folding screen by 17th century artist Chông Yu-sûng, “Six Chinese Sages in Landscapes,” and the eight-panel screen, “Bamboo through the Four Seasons,” by 18th century artist Yu Tôk-chang. The latter is regarded as the most important Korean literati screen in the West, Mowry said.

“We now have the finest and most comprehensive collection of Korean art in the West,” Mowry said. “Korea is important in and of itself, of course, but also as the cultural and artistic bridge linking China and Japan. It’s essential in understanding the relationships among these three great cultures.”