Recalling patriotic words on Memorial Hall birthday

First Commencement dinner held there 130 years ago

“…united we are forever invincible….”

– William Francis Bartlett

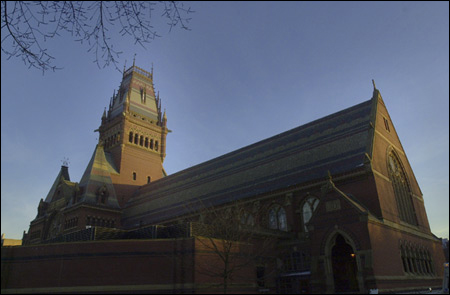

June 23 is the 130th anniversary of the dedication of Memorial Hall Transept and Alumni Hall, now known as Annenberg Hall. Memorial Hall was built to honor the Harvard men who died fighting for the Union in the Civil War. The feelings that Civil War memorials evoked in the 19th century can be compared with those evoked by monuments of our time – such as the Vietnam War Memorial. Harvard’s memorial was to be a unique building that would include a theater and large dining hall. The dedication was the culmination of years of effort, particularly by an alumni group called the “Committee of Fifty.” In fact, it was Harvard’s first major fundraising drive. But it was the following day, June 24, 1874, at the first commencement dinner held in Memorial Hall, that Brevet Major General William Francis Bartlett gave a speech that resounded throughout the nation.

Bartlett, Class of 1862, was a junior at Harvard College when the Civil War started. His first military service began on April 17, 186l, with the 4th Battalion Massachusetts Volunteer Militia. On July 10, 1861, he accepted a commission as captain of the 20th Massachusetts Volunteer Infantry, known as “The Harvard Regiment” because so many of its officers were Harvard students. Bartlett’s first serious action was at the battle of Ball’s Bluff, Va. – a particularly devastating day for the men of the 20th Massachusetts.

Bartlett’s first injury was at the siege of Yorktown on April 24, 1862. He was hit by a sharpshooter and his leg was amputated four inches above the knee. However, he continued to serve. At the battle of Port Hudson, La., on May 27, 1863, Bartlett knew he couldn’t lead the regiment with his wooden leg so he rode a horse into battle. After the battle, Confederate officers asked about the man on horseback. They said, “He was a gallant fellow … We thought him too brave a man to be killed, and ordered our men not to fire at him.” Nevertheless, Bartlett was in the line of fire and was severely wounded in his arm and other foot.

After recuperating from this injury, he returned to service as colonel of the 57th Massachusetts Volunteers. On July 30, 1864, Bartlett was taken prisoner during the assault on “the Crater” at Petersburg, Va. He suffered a serious illness during his two months in prison. The ordeal was made worse by reports that he would soon be exchanged for a Confederate prisoner – only to have the process repeatedly delayed.

The prisoner exchange finally took place in September 1864. On March 13, 1865, at the age of 24, Bartlett was promoted to Brevet Major General, U.S. Volunteers. But his health was ruined. He sailed to Europe in October 1865 with his new bride, Mary Agnes Pomeroy of Pittsfield, Mass., to recuperate. He resigned his commission after returning home in July 1866. He then went into paper and iron manufacturing.

In his autobiography, “Memories of a Happy Life,” William Lawrence, Episcopal bishop of Massachusetts, described the scene at that first Commencement dinner in Memorial Hall. “The ‘bloody shirt’ still waved, and sectional spirit was hot and bitter … the alumni of Harvard, soldiers, sailors, and civilians, dined for the first time in the great Hall dedicated to the dead of the Civil War. The afternoon was hot; many speeches had been made, when General Frank Bartlett, the Chief Marshal of the day was called upon. Gaunt, emaciated, full of spirit, hardly touching his crutches, he stood erect and strong on one leg, and threw into his sentences an even greater courage than he had shown in battle, challenging the Harvard men of the North.”

Bartlett biographer Francis Palfry was also at the Commencement dinner and described the day. “Cambridge commencement dinners are crowded affairs, as a rule, but this day the interest excited by the new building drew together an unusual throng…. A midsummer’s day at Cambridge is apt to be hot and this day was not an exception…. It is not a favorable moment for the debut of an orator. And yet when Bartlett arose, and the first words uttered by his deep and manly voice were heard, and the audience became aware that they came from the shattered soldier whose tall and slender form and wasted face they had seen at the head of the procession as he painfully marshaled it that day, a great silence fell upon the multitude, and he continued and finished his speech in the midst of silence, except when it was broken, as it was more than once, by spontaneous bursts of cheering.”

Bartlett told the audience, “I firmly believe that when the gallant men of Lee’s army surrendered at Appomattox … they followed the example of their heroic chief, and, with their arms, laid down forever their disloyalty to the Union. Take care, then, lest you repel, by injustice, or suspicion, or even by indifference, the returning love of men who now speak with pride of that flag as ‘our flag.’” Bishop Lawrence enthusiastically records that the “speech sounded through New England and the whole county: and the people responded … [and] caught a new vision of patriotism.”

It is a credit to Harvard’s history that the first steps to truly unite the country after the Civil War began in Memorial Hall. It is particularly appropriate that a building dedicated to honor those who died to preserve the Union should be the starting point of this reconciliation.