Westhoff assails FDA on ruling

Says ‘morning after pill’ should be approved for over-the-counter use

Last December, Plan B, the emergency contraceptive or “morning after pill,” which prevents pregnancy when taken within 72 hours of unprotected intercourse, was approved for over-the-counter sale by the Federal Drug Administration’s (FDA) expert advisory panel. But the FDA, contrary to its usual practice, ruled against the panel’s decision and turned down Plan B for over-the-counter use. The reason given was that the drug’s effect on young teenage girls had not been established.

Carolyn Westhoff, a professor of obstetrics and gynecology and public health at the College of Physicians and Surgeons, Columbia University, believes the FDA’s action is the result of “a different political climate in Washington,” and is the first time in her memory that the federal agency has bowed to political pressures.

Westhoff spoke May 17 at Harvard Medical School, delivering the Lawrence Lader Lecture on Family Planning and Reproductive Rights. A leading researcher of the effectiveness and safety of new methods of contraception and medical abortion, Westhoff has served on numerous advisory committees for both governmental agencies and professional societies. In recent years, she has acted as an advocate for RU486 and for emergency oral contraceptives. Her talk, titled “RU486, Plan B, and the Pharmacological Revolution in Reproductive Rights,” was sponsored by the Division of Medical Ethics.

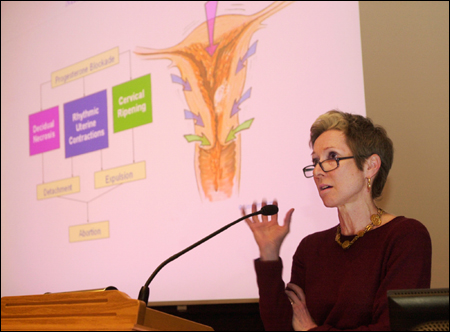

Westhoff explained the difference between RU486, a drug prescribed for medical (rather than surgical) abortion, and Plan B (levenorgestrel), which prevents, rather than terminates pregnancy. RU486, available in the United States under the domestic trade name Mifeprex, induces abortion hormonally if used in the first nine weeks of pregnancy.

Plan B, employing a much lower dose of hormones, interrupts the complex series of events that must take place if pregnancy is to result. Since the drug upsets this process before the blastula implants in the uterus, doctors do not consider the consequence of taking the drug to be abortion.

“The beginning of pregnancy consists of a number of steps,” Westhoff said. “Patients may think that once you have the egg and sperm in the same place, bang, you’re pregnant. But it’s not true. There are many places where a high dose of hormones can interfere with the process.”

RU486 was developed in the 1980s by the European pharmaceutical firm Rousell. It did not win approval by the FDA until 2000, largely because American companies were reluctant to market the controversial drug. Today it is available only through prescription and is subject to restrictions that apply only to the most dangerous drugs, such as Thalidomide and Accutane.

This extreme caution is misplaced, said Westhoff. There have been about 250,000 doses of RU486 prescribed in the United States since the drug was approved, and of that number, only two women have died.

“Any death is tragic, but one in one hundred thousand is about the same mortality rate as surgical abortion, and overall, any form of early abortion is substantially safer than carrying a pregnancy to term. As a society, we’ve become obsessed with the idea that contraception is dangerous when actually the opposite is true. Pregnancy is more dangerous by one or two orders of magnitude.”

According to Westhoff, preventing unintended pregnancies through the use of the morning after pill can help substantially to deal with a serious public health issue.

Of the six million pregnancies that occur each year in the United States, about half are unintended, and of these, about half end in abortion. Since unintended births have a higher morbidity and mortality rate, preventing these pregnancies would produce a healthier population. Making Plan B available as an over-the-counter drug could potentially reduce unintended pregnancies by 1.5 million and reduce abortions by 700,000, she claimed.

The evidence on which the FDA’s advisory panel based its recommendation for approving Plan B for over-the-counter sale, is quite clear, Westhoff said. The drug is chemically similar to birth control pills, and, like birth control pills, has shown no evidence of causing birth defects. The drug has been found to be safe for all women with possible side effects limited to such symptoms as nausea and headache.

“There are no absolute contraindications to the use of Plan B. It’s safe under all circumstances with no danger or overdose,” Westhoff asserted.

Studies have also shown that women who have access to the drug have no tendency to overuse it or to stop using other forms of birth control, suggesting that there would be no downside to making it available over the counter.

“Advance provision is a good thing,” she said.

According to Westhoff, making Plan B available over the counter would not only make good medical sense, but would also help to reach the objectives of the federal government’s initiative, “Healthy People 2010,” which calls for reductions in the number of unintended pregnancies and the number of pregnancies among adolescent girls.

“If we had emergency contraception available in every pharmacy, it would relieve individual problems, individual misery, reduce maternal mortality, and realize the goals in ‘Healthy People 2010,’” she said.