One-third of Americans pray for their health

But does it make a difference?

Mary C.’s baby was born with his intestines twisted the wrong way. She knew he would have to undergo surgery immediately. Mary, a 36-year-old Roman Catholic, e-mailed all those in her prayer circle. Within 24 hours, she had 5,000 people praying for her newborn son. The surgical team untwisted the boy’s intestine, and everything turned out fine.

Did the prayer help? Mary (not her real name) says “yes.” She also admits that the surgeon had a lot to do with the outcome.

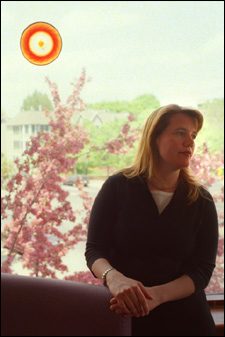

Mary is typical of a group of more than 700 people that Anne McCaffrey, an instructor at the Harvard Medical School, surveyed in her research on prayer and health concerns. “I can’t say that prayer helped her baby,” McCaffrey concludes, “but it certainly helped Mary.”

McCaffrey used the results of a national telephone survey of 2,055 people to probe details of how and how many people use prayer to help them feel better. (Mary was not part of the survey, but McCaffrey talked with her because she is a good example of this group.) The survey found that about 35 percent of people in the United States asked a higher power for help with their health. Of these 719 people, 75 percent prayed to stay healthy and 22 percent prayed for relief of everything from back pain to cancer, headaches to heart problems.

The majority of these people (69 percent) found that doing so was very helpful on a scale of “very helpful” through “somewhat helpful” to “not helpful.”

What is more, some of them gave higher ratings to prayers than to their doctors. Of those who had cancer, 81 percent rated prayer as very helpful, while only 78 percent gave the same high mark to their physicians. For those with severe depression, the score was prayer, 68 percent; doctors, 48 percent.

Women pray more

McCaffrey cautions that that the survey did not ask which of the two was more

helpful. “You can’t compare the two,” she says. “Physicians work toward finding the problem and treating it. Prayer goes to intangibles like coping, putting illness in a larger perspective, and quality of life. It’s like apples and oranges.”

Most of the people questioned did not rely on prayer alone, but used it with conventional and sometimes alternative and complementary medicine. The latter included everything from acupuncture and aromatherapy to megavitamins and yoga. McCaffrey, who received an M.D. from Boston University and then a master’s degree from the Harvard School of Public Health, won a fellowship from Harvard Medical School to look into the information on prayer that was part of the original survey, done in 1997-98.

She found that women pray more that men; those older than 33 years pray more than younger people. Those with educations beyond high school prayed more, as did those suffering from depression, chronic headaches, back and neck pain, digestive problems, or allergies. Doctors generally have less success in treating such ailments than they do alleviating more specific ills like diabetes, and heart, lung, and kidney problems.

A different survey done by other researchers found that 84 percent of 64- to 85-year-olds used prayer as a form of complementary healing. The women prayed more than the men, and the prevalence of prayer did not change with level of education or religion.

McCaffrey was puzzled to find that few of the people she surveyed discussed the therapeutic use of prayer with their doctors. Only 11 percent did so. She doesn’t understand why, and she would like to change the situation. “Patients may consider the two as separate, like church and state,” McCaffrey points out. “As for doctors, we should consider exploring our patients’ spiritual practices to enhance our understanding of their response to illness and health.”

Pray for me?

What does prayer do for people that physicians can’t? McCaffrey says that “it may help them develop an understanding of what’s going on, especially when their disease is painful, troubling, or unexpected. It may improve their quality of life by providing a feeling of well-being. Like meditation, it may aid people to let go a bit.”

By reducing stress, beseeching might also have a physical effect. Stress generates high levels of the hormone cortisol, which suppresses the body’s capacity to fight infection. By lowering cortisol, McCaffrey says, prayer might boost immunity to disease.

Herbert Benson, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School and director of the Mind and Body Medical Institute in Boston, argues that regular prayer, along with general stress management, can reduce visits to doctors and other health professionals by 50 percent. He is involved in studies of whether patients who have others pray for them do better than those who don’t have that backup. Some of these patients are the object of prayers by relatives and friends; others receive the supplications of an organized group praying for them without knowing specifically who they are. Results are not in yet.

McCaffrey notes that some studies conclude that prayer has a positive therapeutic effect, while others do not come up with such healing results. No studies, she adds, have found that prayer makes a difference in the number of days or the number of deaths in places like coronary care units.

Is it possible to prove that prayer has a direct curative effect on disease? McCaffrey doubts it. “You can’t prove that God exists so how can you prove that prayer works?” she says. “People who have faith don’t question the truth of either.”