Ma’s day: Cellist awarded Harvard Arts Medal

Medalist Yo-Yo Ma highlights Arts First

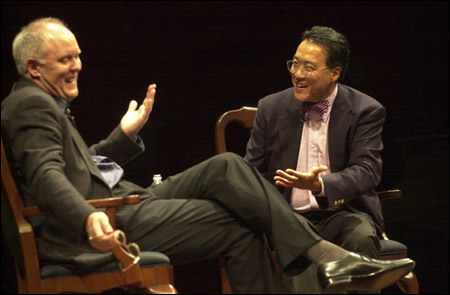

Introducing this year’s Arts First Medalist Yo-Yo Ma ’76 at Sanders Theatre Sunday night (May 9), host and actor John Lithgow ’67 described the ensuing interview as “a private moment with about 1,100 eavesdroppers.” Ma, ever the generous performer, delivered on Lithgow’s promise, sharing secrets that revealed his easygoing humanity and privileged the sold-out audience with an intimate glimpse into his musical life.

The world’s best-known classical musician, for instance, produced such an offensive sound on his first instrument, the violin, that his parents gave up on him up for having no talent. At Harvard, he was a terrible student who nearly

flunked out of music history. His public television performances with Muppets, aardvarks, and a soft-spoken man in a cardigan sweater are among his proudest. And several years ago, after completing an album of tangos by Astor Piazzolla, he announced that he was giving up the cello to take up accordion.

OK, that last one was an April Fools’ Day joke, encouraged by National Public Radio. “The disturbing thing was how easy it was to lie,” said Ma, adding that the prank caused some concerned concert presenters to call and check that he would be playing the cello, as hired.

Playful, thoughtful, and unfailingly gracious, Ma capped Arts First, Harvard’s annual orgy of student artistic achievement and exploration, with an inspirational look into his artistic process. Along the way, he paid homage to the Harvard experiences and professors who informed his rich musical life.

“Without question, everything that I’ve done in the last 10 or 20 years is a direct result of what I was first exposed to at college,” he said in the captivating conversation that preceded a short solo performance. The evening generated a postconcert electricity that buzzed with comments like “the best thing I’ve ever seen at Harvard.”

The ‘pretty good cellist’ finds his sound

Ma, who began studying cello at age 4 and who arrived at Harvard with Juilliard training and a modest performing career already in place, credited several professors – audience members Leon Kirchner and Robinson Professor of Music Robert Levin among them – for turning the self-described “pretty good cellist” into a master musician.

“I could have easily gotten totally lost, except for the fact that a couple of professors really picked me out,” he told Lithgow and Harvard President Lawrence H. Summers in the Green Room before the event.

Kirchner, the Walter Bigelow Rosen Professor of Music Emeritus, dubbed himself Ma’s “boulder in the road” and made it his duty to present obstacles that would, in the overcoming, create a more thoughtful musician. “He said, ‘You play pretty well, but you just don’t understand that music is powered by ideas. Until you understand that, you will not find your sound,’” said Ma, admitting, “I had no idea what he was talking about.”

At Harvard, Ma said, he was forced to think about why he played the way he did, who was the composer and why did he or she write the piece. “That was the beginning of my waking up to an engagement with a life in music,” he said. Ma’s own prodigious facility for the cello might have been another boulder in his road, allowing him to play with virtuosity but not meaning. “It’s good to have facility, but it’s really good to make sure what you’re facile at serves a purpose.”

Ma described yet another boulder – being put on academic probation during his

freshman year at Harvard – that proved a worthy obstacle. Oversleeping three alarm clocks and missing a final, he said, he was required to remain on campus for the following semester instead of touring on weekends.

“Staying on campus made me realize what an incredibly rich community this was,” he said, adding that he took gleeful advantage of the many musical opportunities on campus to play with a variety of ensembles. “It was the first time I met an intact community that was not a specialized community.” Because he was playing with and for nonmusicians as well as very serious musicians, he said, “there was less of a shorthand and that forced me to communicate differently.”

Indeed, Ma’s musical inquisitiveness remains undiluted; as an ensemble of students opened the program with a performance of Franz Schubert’s “Trout” Quintet, Ma dashed from the Green Room and crouched at the entrance to Sanders Theatre so he wouldn’t miss a note.

Content, communication, reception

No one who has seen Ma play was surprised to hear him describe the communication that is at the heart of the musical experience. Performance, he said, comprises content, communication, and reception. “Your work is not done until that thing that you are really trying to advocate for … is really received by somebody,” he said.

Acclaimed for expanding the cello repertoire and for his genre-busting

explorations of music from around the world, from the Kalahari of Africa to the string rhythms of Appalachia, the 14-time Grammy award-winner listens to a wide range of music. “By listening to a lot of different types of music and engaging in different types of music, I have a deeper understanding of music itself,” he said in a question-and-answer session with audience members. Friends’ and colleagues’ suggestions as well as tunes from his daughter’s iPod provide variety and challenge his ears.

That musical curiosity is at the core of his performance career. “There are so many ways to express important things. If you find that somebody has another way, you’re fascinated,” he said. “Every time [I] take the risk and [I] go someplace that’s scary and unknown … I come back a better musician.”

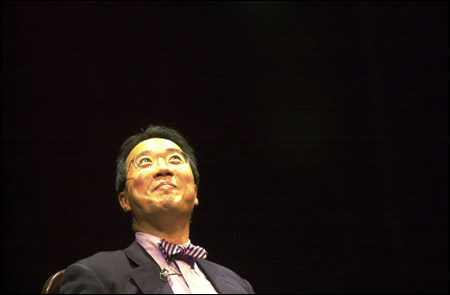

Still, Ma concluded the evening with the distinctly familiar and un-scary Bach Cello Suite No. 1. He played the trancelike Prelude twice, once on a baroque cello for Lithgow, who had missed it when he arrived late to a performance in Los Angeles, and then on a modern cello with the rest of the suite. True to the words he shared with the “eavesdroppers” of the audience, Ma inhabited Bach’s work and radiated it joyfully, drawing an intimate circle that brought the last seat of the balcony into the music as tightly as Lithgow, who sat onstage beside him.

Summers, who had the unenviable job of presenting Ma with the Harvard Arts Medal following his performance, made appreciative and succinct remarks. “When we honor someone, we really are in a sense honoring ourselves,” he said. “Surely, Yo-Yo Ma honors us with his presence tonight.”

The event also honored student composer Anthony Cheung ’04 with the Louis Sudler Prize for undergraduate accomplishment in the arts.