Cancer drug’s effectiveness newly understood

Patient’s genetic context determines drug’s success

Two teams of Harvard researchers have handed doctors a new weapon against lung cancer by explaining the peculiar success of a drug that is extremely effective against the nation’s top cancer killer, but only in a small percentage of cases.

The findings, published separately last Thursday (April 29), provide physicians with a blueprint of how and when the drug, called Iressa, can be most effectively used to help lung cancer patients.

Iressa was approved by the Food and Drug Administration last May after it proved able to shrink tumors dramatically – between 50 percent and 90 percent – in about one in 10 of the patients who took it. At the time, however, it was poorly understood in which cases the drug would prove effective.

The researchers, from Massachusetts General Hospital (MGH) and the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, have solved that mystery, showing that the drug is 10 times more effective against lung cancer cells that have a certain genetic modification.

The results highlight the promise of a new generation of medicine, where broad spectrum treatments like chemotherapy can be augmented or even replaced by drugs that target the specific characteristics of an individual or an illness, providing more effective, customized care.

Cancer patients, doctors, and advocacy groups across the country welcomed the news. Lung cancer, which results in about 155,000 deaths annually, is America’s No. 1 killer of both men and women. Iressa proved effective on a type of nonsmall cell lung cancer that makes up about 85 percent of lung cancer cases. Researchers estimated it could help about 17,000 patients a year.

“This study indicates potentially better outcomes for 10 to 15 percent of those diagnosed with nonsmall cell lung cancer, primarily nonsmoking women, and while it may not have a huge impact in terms of sheer numbers, it is a major step forward,” Harmon Eyre, chief medical officer of the American Cancer Society, said in a statement released Thursday. “This study has tremendous significance for the future of targeted therapies. It demonstrates that human genome sequencing can identify in cancers what genes are mutated or expressed inappropriately and so enable consideration of very targeted therapies.”

How Iressa works

Professor of Medicine Daniel Haber, director of Massachusetts General Hospital’s Cancer Center, said he became interested in Iressa, which is also called gefitinib, after reading an account of a lung cancer patient who had experienced a dramatic improvement after taking the drug.

An expert in breast cancer genetics, Haber said the story had the hallmarks of a case where a genetic mutation had occurred in the cancer, rendering the mutated cells susceptible to the drug.

Haber and his colleagues at MGH examined the genetic makeup of tumors from patients in the Iressa trial, looking for genetic mutations that could explain the patients’ different reactions.

In eight of the nine patients who had responded to Iressa, researchers found specific mutations in the gene for a receptor on the surface of the cancer cell. That receptor is a place where a protein called epidermal growth factor attaches to the cell and instructs it to begin growing.

None of the patients whose cancer didn’t respond to Iressa had the same genetic mutations.

At the same time, researchers at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, and the Broad Institute at M.I.T. and Harvard reached the same results by taking a different route.

The researchers were searching for mutations in the family of enzymes called tyrosine kinases, one of which is the epidermal growth factor receptor. They hoped that mutations they found could provide a pathway to a drug that could be used to combat lung cancer. To their surprise, the first mutation they found involved the epidermal growth factor receptor in nonsmoking Japanese patients, a group that had shown the best response to Iressa.

The researchers then scanned tumors from 58 Japanese and 61 American lung cancer patients. They found epidermal growth factor receptor mutations – as did the MGH researchers – in 15 Japanese, but just one American.

The Dana-Farber researchers also scanned tissue from a particular type of lung cancer, called adenocarcinoma, which spreads to the lining around the lungs and which has been found to be responsive to Iressa. Again, they found the same genetic mutations.

Finally, researchers analyzed tumors from five patients who had responded well to Iressa and four who hadn’t. All of those whose tumors had shrunk when treated with Iressa had the same genetic mutations. None of the four whose cancer hadn’t responded had the mutations.

Iressa was designed to attach to the “kinase” module of the epidermal growth factor receptor, which itself is on the surface of the lung cancer cell. Iressa blocks the signals from the receptor that stimulate growth of cells.

Haber said the mutations appear to have been selected by the cancer cells, since they result in a stronger growth signal. Normally, when epidermal growth factor attaches to its receptor on the cell surface, it functions for just 15 minutes. In cells with the mutated gene, the receptor stays active for as long as three hours, Haber said.

The mutations, however, also heighten the receptor’s susceptibility to Iressa, making cancers that have these mutations about 10 times more sensitive to the drug than other types of lung cancer.

Future directions

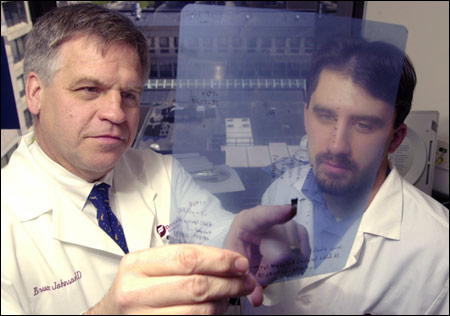

Researchers at both MGH and Dana-Farber said their work on Iressa and on similar compounds will continue along several lines. A clinical trial is planned that will pre-screen patients’ tumors for the genetic mutation and test them against a control group of patients without the mutation, according to Assistant Professor of Medicine Bruce Johnson, one of the co-authors of the Dana-Farber paper published in the journal Science.

Haber, a co-author of the MGH paper published online by the New England Journal of Medicine, said researchers will also be re-examining past drug trials for drugs that had proven effective in a small number of patients. Haber said in the past a drug that was effective in just 10 percent of cases was usually discarded. Now, researchers will be examining some of these compounds to see if they might represent another targeted treatment.

Haber said MGH researchers are also examining other cancers to see if they have similar mutations, but have so far been unsuccessful.

“We’ve looked and looked and looked but so far found no other cancers in which these mutations are common,” Haber said.

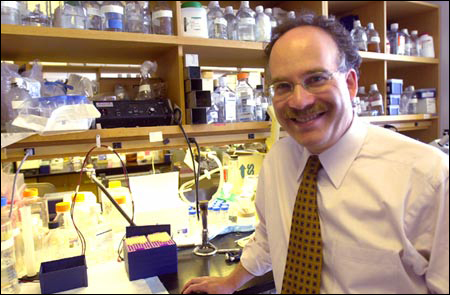

Assistant Professor of Pathology Matthew Meyerson, a co-author of the Dana-Farber paper, said research will continue to systematically examine genes similar to the epidermal growth factor receptor, known as protein kinases, for mutations in cancer. That research is led by Meyerson and by Assistant Professor of Medicine William Sellers, another co-author of the Dana-Farber paper.

Over time, Meyerson said, if targeted treatments are found for different subtypes of various cancers, he hopes they will someday combine to provide a comprehensive yet targeted way to treat the disease with greater effectiveness and fewer side effects.

“That’s definitely our dream,” Meyerson said. “It’s the dream of many, many people in the cancer field.”