‘What if?’

Novelist Bernays and artist McGhee stir up students’ imaginations

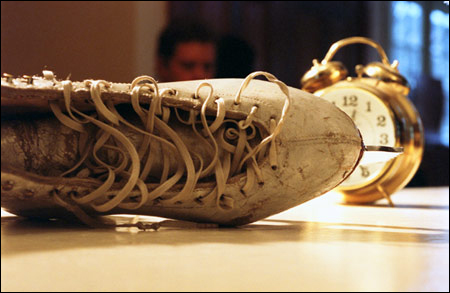

A bunch of leeks, an alarm clock, a nylon rope, a banana, three playing cards, an ice skate – what does that suggest to you, Dr. Watson?

I can’t say, Holmes, I’m at a complete loss.

Well, then, why don’t you just make something up?

We know, of course, that Sherlock Holmes would never say such a thing. Holmes’ method is always one of pure deduction. Eliminate the impossible and whatever remains, however improbable, must be the solution. But the idea of making something up would have been extremely congenial to the creator of Holmes and Watson, Sir Arthur Conan Doyle.

Every writer of fiction makes things up, from Doyle to Dostoyevsky to Danielle Steele, a fact well known to Anne Bernays, a Cambridge-based novelist who teaches creative writing at the Nieman Foundation for Journalism.

“There’s a woman walking up and down in front of your house smoking a cigarette. Who is she? Why is she there?”

Presenting her students with hypothetical situations like this is one of Bernays’ chief methods for getting them to exercise their imaginative muscles. It is also one of the strategies she uses in the book she wrote with Pamela Painter, “What If? Writing Exercises for Fiction Writers” (HarperCollins, 1990).

Bernays says that her journalist students often need a bit of reprogramming.

“They’ve been taught never to make things up, so it can be hard for them to use their imaginations, at least at first.”

On April 13, Bernays and Anne McGhee, a lecturer in landscape architecture and a teacher of drawing and painting in the Graduate School of Design, collaborated on an experimental joint teaching exercise. The students came from Bernays’ writing class and McGhee’s drawing class. Bernays herself was in a somewhat anomalous position since in addition to teaching writing she is also one of McGhee’s students.

The two teachers have found that while the medium in which they teach differs, their approaches have pronounced similarities.

“We both teach by doing exercises, with as little theory as possible,” said Bernays.

“We wanted to have an interactive exercise that would hopefully stimulate your imagination, your sense of play, and your creativity,” McGhee told the students.

The students confronted a table on which were displayed a selection of objects whose randomness and incongruity might have baffled even the great detective. The writers’ assignment was to pick three of the objects and make up a story about them. The artists were simply to draw any or all of them, as they chose.

After about 30 minutes during which the only sounds were the furious scratching of pens and pencils, the students read or displayed their work. There were stories about an elderly woman with a penchant for card games, a homeless alcoholic wearing one ice skate, a dog who saves his mistress from suicide by devouring a bunch of leeks. The drawings were descriptive of physical reality in a way the stories were not, but an equal measure of imagination could be seen in the way the artists dealt with line, texture, color, light, and shade.

Afterward, Bernays said she thought the experiment had been a great success and looks forward to repeating it in the future.

“I think everyone left feeling very enthused about it,” she said.