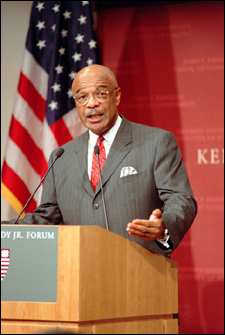

Rod Paige offers high praise for No Child Left Behind

Education secretary marks 50th anniversary of Brown decision with Kennedy School keynote address

Fifty years after Brown v. Board of Education officially opened the door to

racial equality in the United States, “education is still the best place to continue pushing for change,” U.S. Secretary of Education Rod Paige told a packed audience at the Kennedy School of Government Thursday (April 22).

In his keynote address for a conference marking the golden anniversary of the Supreme Court’s decision to end racial segregation in American schools, the secretary lauded the verdict as one of the finest moments in American judicial history. But a half-century later, there is still much ground to cover, Paige said. “Education is the battlefront; there are islands of true excellence in education … but millions of children in this country are still being left behind.”

Paige’s provident opening speech set the tone for the conference, held April 22-24 by the Kennedy School’s Program on Education Policy and Governance. Convened at a critical juncture in history – 50 years since Brown and 25 years before the Supreme Court-mandated end of affirmative action in university admission policies – the conference, titled “50 Years After Brown,” examined both the impact of the historic Supreme Court decision, and the promises it has yet to fulfill. Panel discussions focused on issues facing elementary and secondary education: the role of preschool programs in closing the achievement gap; the connection between academic funding and student achievement; the effect of education accountability systems; and the impact of school choice.

Formerly the superintendent of the Houston Independent School District, Paige came to national attention when, in 2001, President George W. Bush appointed him

Paige offers some answers

Following his speech, Paige took questions from the audience, many of whom were students of educational policy at the Kennedy School of Government and the Harvard Graduate School of Education. Though he declined to answer any questions about his recent off-the-cuff and admittedly ill-advised characterization of the National Education Association (NEA) as a “terrorist organization” – Paige dismissed one student’s query about the incident with the cogent statement: “I’ve had many opportunities to comment on that and I don’t have anything to add to it; my comments stand as they were made” – he did engage in open debate when others raised questions about NCLB. Several questions were raised about NCLB’s emphasis on high-stakes tests: Did he worry that such a goal would make educators “teach to the test?” How did he justify linking high school graduation to one single exam? What good will those tests be if teachers are not taught to use the data they provide?

Paige answered each question by reminding the audience that the pace of change is often slow. Indeed it takes time to coordinate all the resources across each state, but “we hope the tests are aligned specifically to the standards states have set,” he explained. The tests and standards should be “the same thing.” If teachers are “teaching to the test,” then that means they are simply teaching important material kids need to know, he said.

Paige again defended the content and design of the test itself when answering questions about its ‘high stakes.’ “The highest stake of all is a child not getting an education,” said Paige, in response to a criticism of its severity. “We should enable success, but I don’t object to making decisions based on how a student performs on a valid, reliable, objective assessment tool.”

It is this information that will change the face of American education, Paige argued. Once student performance data is disaggregated and made visible, he said, teachers will get feedback about the true state of education for every ethnic group. They must use that data to inform their lessons, said Paige, and to directly address the achievement gap. “Dissatisfaction is a powerful motivator for action,” he reasoned. “The reasons to assess is to get more information.” the seventh U.S. secretary of education. Bush cited Houston as a model school district; under Paige’s leadership, test scores rose 20 percent and the dropout rate decreased by half, even as the district’s proportion of low-income students increased by 13 percent. Paige’s emphasis on accountability, high-stakes testing, and high expectations for all students were commended by the president, and are now central components of his sweeping educational reform plan, No Child Left Behind (NCLB).

In his speech, titled, “Beyond Brown: Unfinished Business,” Paige repeatedly praised the NCLB plan, calling it the next logical step to Brown. “Brown opened the door to equality,” Paige said. “Now NCLB can provide something of substance inside the building.”

The most sweeping federal educational legislation to date, NCLB was passed in 2002 with strong bipartisan support. It has since become a lightning rod of controversy for educators, parents, administrators, and policy-makers. Aimed at narrowing the achievement gap that exists among different ethnic groups, the policy requires states to implement accountability systems for all students in the public schools. Both students and teachers must meet standards; states must develop progress goals and annual tests to ensure that all students reach proficiency within 12 years. School districts and schools that fail to show adequate yearly progress will be subject to improvement, corrective action, and restructuring measures aimed at helping the school and its students meet the standards.

According to Paige, despite the years of effort since Brown to equalize education, the achievement gap persists as our most pressing social problem. “It is the civil rights issue of our time,” he asserted. Despite some recent improvement, studies show that by the time students reach the 12th grade, only 1 in 6 black students, and 1 in 5 Hispanic students can read at grade level, Paige said. Math scores are even more shocking: only 3 percent of blacks and 4 percent of Hispanics test at proficient levels by their senior year.

“It is devastating for a child to be provided no intellectual tools, and to be set adrift with no means of finding his way back,” said Paige. “When a child is left behind, it is not just a problem for that child, it is a problem for the rest of the nation.”

Although Paige cited evidence from a recent report by the Council of Great City Schools that indicated students in the largest urban school districts had shown improvement under NCLB, he cautioned educators and policy-makers not to rest on their laurels. There are profound consequences for our children and our nation if we don’t build on this progress, he cautioned.

With so much work ahead, legislators must strive for common goals that can be championed by members of both political parties, said Paige. Without bipartisan support, there will be no meaningful, lasting reform. Resistance to Brown was massive and was sustained over generations, Paige explained. “We can’t afford to have that long an argument over this. Those who fought against Brown were on the wrong side of history. I believe those who fight against NCLB will be judged so as well.”