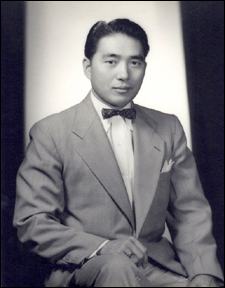

Morimoto, 86, adviser, friend to generations of students

Obituary

Kiyo Morimoto, who helped tens of thousands of students adjust to college life

in his 27 years at Harvard’s Bureau of Study Counsel, and who served for six years as the bureau’s director, died Feb. 22 at the age of 86.

Born in rural Pocatello, Idaho, to parents who had emigrated from Japan in 1912 and worked as tenant farmers growing potatoes and sugar beets, Morimoto left school at 15 to help his family work the land. Ten years later, the day after the Japanese attacked Pearl Harbor, he enlisted in the U.S. Army.

He was assigned to the all-Japanese-American 442nd Regimental Combat Team, one-third of whom came from the internment camps that the U.S. government established for Japanese Americans during World War II. Morimoto’s family and other Japanese who lived too far from the coast to be considered a threat to U.S. security were spared imprisonment. The unit was one of the most highly decorated in American military history. For his service in France and Italy, Morimoto won the Silver Star and Purple Heart.

After the war, he took advantage of the G.I. Bill to attend Idaho State College, earning a bachelor’s degree in sociology in 1950. He earned a master’s degree in sociology from Boston University in 1952. After working on a number of research projects (including an early study conducted by the Boston Psychiatric Hospital on the effects of LSD) and attending graduate courses at Harvard, he took a job as a counselor at the Bureau of Study Counsel in 1958.

In that capacity, he supervised and trained counselors, ran sessions for graduate teaching assistants, instructed students in reading skills, and personally counseled more than a dozen students per week. Morimoto was also a member of the Faculty of Arts and Sciences and a lecturer on education. He taught courses in the School of Public Health, the Business School, and the Graduate School of Education.

As a counselor, Morimoto was renowned for his ability to listen to students’ problems in a sympathetic, nonjudgmental way. An article by Brina Caplan in a 1985 issue of Harvard Magazine, the year he retired, quoted him as saying that “the individual is the expert on his or her experience.”

His adherence to this philosophy created a gently accommodating atmosphere in which students were able to disburden themselves of fears, insecurities, and other self-defeating thoughts and free up energy for their work. Morimoto’s approach to counseling, Caplan writes, “offers those discredited, abandoned aspects of the self a way ‘to be welcomed into life.’”

Part of what made Morimoto such an effective counselor was the richness of his life experience. While in the Army, he graduated from cooks and bakers school (he later displayed his diploma on his office wall at Harvard), and while in Italy after the fighting was over, he took voice lessons and seriously considered a career in opera.

While working toward his master’s degree, he supported himself in many ways, including working on the railroad in Philadelphia (he knew how to shoe a railroad car) and working for the president of Boston University as a butler and handyman.

His early experiences in Idaho also contributed to his ability to understand those who felt marginalized or out of place. He often said that growing up as a Japanese American in the predominantly white Tyhee section of Pocatello, near a Blackfoot Indian reservation, made him a natural anthropologist.

While at Harvard, Morimoto served as a member of the first faculty and administrative advisory committee of the Harvard Foundation. S. Allen Counter, the foundation’s director, remembers him as “a wonderful person who was very supportive in his work with students.” Counter said that Morimoto helped to reach out to Asian students during the early days of the foundation and helped organize a successful conference on the internment of Japanese Americans during World War II.

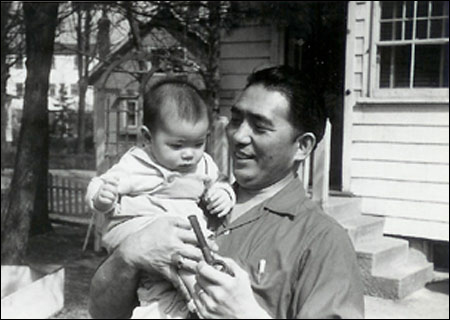

Morimoto is survived by his sister Miye Hikida and his brother Doug of Pocatello, Idaho; his wife, Lorinda Gannon Morimoto of Templeton, Mass.; his former wife, Francoise Robitaille Morimoto of Rockland, Mass.; and three children, Monique Morimoto-Flaherty of Quincy, David of Watertown, and Philip of Somerville.

Thanks to David Morimoto who supplied much of the information on which this article is based.