High-dose drugs prevent heart deaths

Outperform standard medications

If you want to increase your chances of living longer, taking cholesterol drugs is an easy way to do it. That’s the message from a Harvard study of 4,162 people hospitalized in 350 places in eight countries. It is the first research to show that intense lowering of cholesterol results in a major reduction in deaths and major heart attacks.

All of the patients had recently suffered a heart attack or uncontrollable heart pains (unstable angina). About half of them were given a standard dose (40 mg) of Pravachol (pravastatin); the other half received the highest dose available (80 mg) of Lipitor (atorvastatin). The latter is eight times as powerful as the former. Two and half years later, deaths from all causes in the Lipitor group had been reduced by 28 percent.

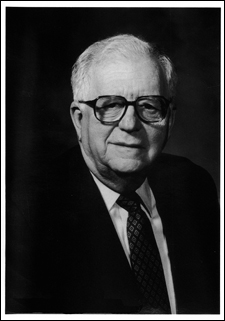

“In 50 years of seeing heart patients and doing cardiovascular research, this is one of the most exciting developments I’ve witnessed,” says Eugene Braunwald, Hersey Distinguished Professor of Medicine and chairman of the group that conducted the study.

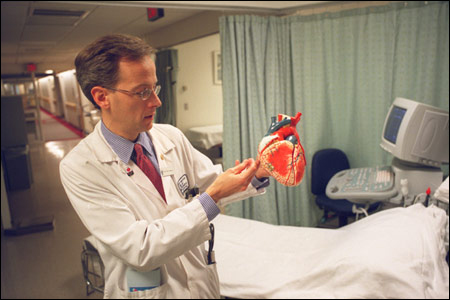

“Starting immediately, patients going home from the hospital after a heart attack should be put on a high-dose statin,” says Christopher Cannon, an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School who led the study. He and others in the research group believe the implications of the study extend to people all over the world.

“Our results should be a wake-up call to everyone with heart disease or high cholesterol,” Cannon comments. “Patients need to speak to their doctors about the appropriate dose of statins, so that they can prevent a future heart attack or coronary death.”

Big surprises

The study, called PROVE IT, for Pravastatin or Atorvastatin Evaluation and Infection Therapy, was based at Brigham and Women’s Hospital, a Harvard affiliate in Boston. And for several reasons the results involved major surprises.

The sponsor of the research, Bristol-Myers Squibb, maker of Pravachol, expected to prove that this drug is just as good as its more potent rival Lipitor, made by Pfizer. “We were as surprised by the findings as the sponsor,” Braunwald notes. “To their great credit, the company was totally supportive in our making the results public soon after they were available.”

The surprises extend to the roots of basic research and to the practices of doctors worldwide. “There was a common belief that once you lower harmful low-density cholesterol to 100 milligrams per deciliter, you achieve little further gain by going any lower,” Braunwald points out. “Certainly, that’s what I believed. But those who took the high-dose statin reached a level of about 62, and over two and a half years these people enjoyed a 16 percent lower risk of heart attacks, stroke, bypass surgery, rehospitalization for cardiac events, and death from all causes.”

Another unexpected outcome was rapid response. “We began to see the benefit after only 30 days of intensive lowering of bad cholesterol,” Cannon notes. “That compares to a year or 18 months for benefits to start in more stable patients.”

In most people, regular doses of statins can lower high levels of bad or low-density cholesterol by about 25 percent. “The high dose given in PROVE IT dropped levels another 25 percent for a total of 50 percent,” Cannon points out. “Total cholesterol levels fell to 130. That’s significant.”

Makers of some breakfast cereals, herbs, multivitamins, and dietary fiber claim their products lower cholesterol without the use of drugs, but their numbers don’t compare with those offered by potent statins. “Cheerios may drop your cholesterol by 5 to 6 percent if you watch your diet and exercise regularly,” Cannon says. “But that pales against the 50 percent reduction that dropped low-density cholesterol levels to 62.”

Benefit versus cost

Braunwald is careful not to overextend claims for the benefits of high-dose statins like Lipitor and Zocor. “The trial involved only people hospitalized

with recent heart attacks or uncontrollable angina,” he notes. About 2 million people a year in the United States fit that category; worldwide, Cannon puts the number at 4 million to 6 million. PROVE IT did not include people with various forms of stable coronary artery disease and hazardously high levels of cholesterol.

But doctors who treat patients every day, including Cannon and Braunwald, see little risk in prescribing statins to drive total cholesterol levels down to 130 and low-density levels below 100. “In patients with coronary heart disease, I’d like to drop low-density cholesterol below 70,” he says.

They and their colleagues report on PROVE IT results in the April 8 issue of the New England Journal of Medicine. In an editorial accompanying the report, Eric Topol of the Cleveland Clinic Lerner College of Medicine points out that an estimated 36 million people in the United States “should be taking a statin, but only 11 million are currently being treated. Worldwide, the discrepancy is even more staggering; more than 200 million people meet the criteria for treatment but fewer than 25 million take statins.”

One reason is cost. A starting dose (10 mg) of atorvastatin costs about $900 a year; the 80 mg. superdose runs around $1,400 a year. Cannon claims such costs are overridden by the benefits, by a reduction in heart attacks and hospital visits for things like clearing plaque from arteries and for bypass surgery. “I think it’s one of the best values in medicine,” he says.

Side effects

To get and keep cholesterol down, people may have to take statins for most of their lives. What about possible side effects? Postmenopausal women were advised to take estrogen and other hormone replacements to prevent heart attacks. But studies now show that long-term use of these drugs both fail to protect against heart disease and raise the risk of breast cancer.

Braunwald believes the statin study sits on a much firmer scientific base than hormone replacement ever did. He also feels that many doctors have shared the experiences that he has. “I have been prescribing these drugs since 1987,” he says. “I find them to be safer than we first thought.”

Cannon describes statin side effects as “mild and reversible.” Some people may get muscle cramps. Others may develop severe liver or muscle abnormalities, but that is rare and disappears when they stop taking the drug.

Neither Braunwald nor Cannon thinks that statin pills should be used as an excuse for not exercising or eating a healthy diet. “You can have diabetes, high blood pressure, and be obese, even if your bad cholesterol is at a good level,” Braunwald points out. “Smoking can give you lung cancer even if your cholesterol is low. Statins should be part of a healthy lifestyle for patients with coronary heart disease, not a substitute for it.”

“People with high cholesterol should not feel guilty, should not think they’re doing something wrong,” Cannon adds. “Genetics is, by far, the main cause of it, and it’s now very treatable. Forget about trying to lower your cholesterol with Cheerios, and ask your doctor about statins. They’re a terrific way for people with high cholesterol to prevent heart attacks and coronary death.”