The grace and wisdom of Suzanne Farrell

Joan Acocella, dance critic for the New Yorker, introduced the video as “one of the most extraordinary pieces of dance footage I have ever seen.”

Joan Acocella, dance critic for the New Yorker, introduced the video as “one of the most extraordinary pieces of dance footage I have ever seen.”

The 40-year-old tape, taken by an audience member, showed a young woman in a filmy white costume dancing with fluid grace combined with furious, almost demonic, energy. The intricate steps, executed at breakneck speed, make one wonder how an ordinary mortal could actually move that way.

Meanwhile, the subject of the video, Suzanne Farrell, sat straight-backed, legs primly crossed, before a capacity audience in Lowell Hall. The woman whom Acocella, the moderator of the event, called “the most influential ballerina America has ever produced,” was at Harvard April 15 for “An Evening With Suzanne Farrell,” presented by the Office for the Arts, in association with the Harvard Theatre Collection. The following day Farrell, who is the 2003-04 Ruth Page Visiting Artist in Dance at Harvard, taught a master class for student dancers.

Born Roberta Sue Ficker in a suburb of Cincinnati and raised by a devoted single mother who moved the family to New York City so that her three daughters would have a chance to excel in the arts, Farrell became a star of the New York City Ballet while still a teenager.

Her emergence from the corps de ballet came about in true “42nd Street” fashion when the principal female dancer of a new ballet choreographed by the legendary George Balanchine became pregnant and dropped out. The male dancer Jacques D’Amboise believed Farrell could learn the role and convinced Balanchine to give her a chance.

Enchanted by her ability, Balanchine not only gave her a chance, he featured her in ballet after ballet. Except for an interruption of a few years when Farrell left to dance with Maurice Béjart’s company in Brussels, their partnership continued until Balanchine’s death in 1982.

Dance, the most evanescent of the arts, depends for its technique and inspiration on the subtle, often ineffable relationship between student and teacher. As a result of such relationships being perpetuated from generation to generation, artists of the present may be able to benefit from the aesthetic tutelage of the giants of the past. Through her relationship with Balanchine, and his with the early 20th century Kirov Ballet and Ballets Russes of Sergei Diagelev, this was the sort of opportunity that Farrell brought to Harvard.

“Mr. Balanchine’s classes were not designed to make you feel good,” Farrell said of her former mentor. “It was like going into a laboratory. He never chastised you for doing something wrong. Often you felt your technique was getting worse because you were doing things you’d never been trained to do. It was endlessly fascinating.”

Since 2000, Farrell has directed The Suzanne Farrell Ballet under the auspices of the Kennedy Center in Washington, D.C., and is a full-time professor in the dance department of Florida State University in Tallahassee. She said that she loves to teach and implied that teaching has fulfilled a need in her life that nothing else quite satisfied.

“There are no courses to teach you how to be an ex-ballerina,” she said. “The hardest part about retirement was that I couldn’t listen to beautiful music anymore because it made me want to dance. When I began teaching, I could respond to music through my students.”

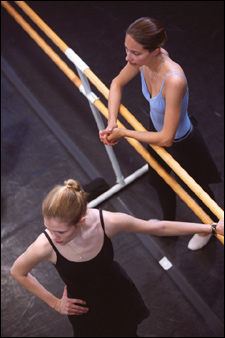

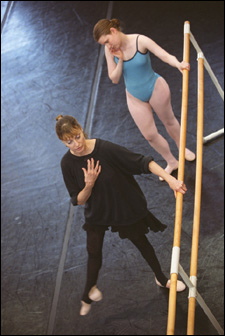

Farrell’s love of teaching became apparent the following day when she conducted a class for a group of Harvard ballerinas in the Rieman Center for the Performing Arts. Dressed in a baggy black sweater, a short skirt and black tights, she walked among the students, lifting an arm here, adjusting a head there, reminding them gently what it means to be a dancer.

“The most important thing is that every time you come to class, you should feel as if it’s a new beginning of your life.”

Her comments seemed geared most of all to banishing tension and nervousness, encouraging the dancers to enjoy themselves.

“Breathe energy…. Take the fear factor out of your face.” And the great lesson that Balanchine had imparted to his students: “Don’t be afraid to make mistakes.”

To one very short dancer she gave the advice: “Hold your head up. Height is an illusion. It doesn’t matter how tall you are.”

And to the class as a whole, she revealed this dancer’s secret: “When the hard part comes, everyone starts to look down and become very internal. When the hard part comes, that’s when you have to get bigger!”

After a series of exercises at the barre, and another series on the open floor, Farrell ended the class by having her students perform a movement designed to evoke this sense of magnitude, this willingness to fearlessly command space. One by one, the students moved across the floor in a series of leaps and pirouettes, and at the height of their last jump, they were to shout out their names.

“That’s why they have cheerleaders at football games. You have to be your own cheerleader, you have to create your own motivation.”

Not all the names were audible. The cavernous space seemed to swallow up the sound. And making an articulate shout at the height of physical exertion is probably not something that comes naturally anyway.

But there was this to be said for Farrell’s teaching: The shortest dancer seemed to shout the loudest, and really did seem to become taller.