Remembering Thurgood Marshall

Former clerks of Supreme Court justice offer personal perspectives on one man’s legacy

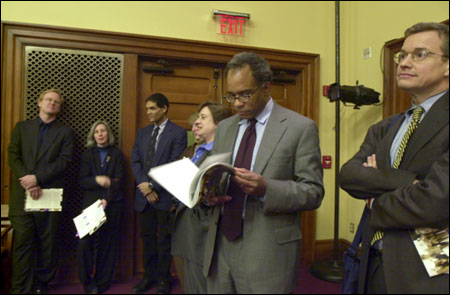

Marking the 50th anniversary of the landmark Brown v. Board of Education decision that desegregated America’s schools, Harvard Law School (HLS) turned its attention Tuesday night (April 13) to Justice of the United States Thurgood Marshall, who as legal director for the NAACP successfully argued the Brown case. Yet with a panel of eight HLS faculty members who clerked for Marshall, the event painted a far richer portrait of the civil rights leader than is well known. The panelists shaded his august jurisprudential legacy with personal recollections of Marshall as a boss and mentor who told salty stories, gambled with passion, and called his clerks “knuckleheads.”

Moderated by Climenko Professor of Law Charles Ogletree Jr., coordinator of HLS’s weeklong celebration of Brown (see sidebar), the panel included eight of the nine HLS faculty members who served as Marshall’s clerks: Scott Brewer, William Fisher, Howell Jackson, HLS Dean Elena Kagan, Randall Kennedy, Martha Minow, Carol Steiker, and David Wilkins.

“It is a rather striking fact that one-eighth of the Harvard Law School faculty clerked for Justice Thurgood Marshall,” said President Lawrence H. Summers in opening remarks. “It speaks to the Harvard Law faculty and the moral commitment of so many of its members.”

April 15-18: 50th Anniversary of Brown v. Board of Education at Harvard Law School (HLS) continues

The Harvard Law Review will hold a symposium on Brown v. Board of Education today (April 15) at 6 p.m. in the Ames Courtroom, HLS. Panelists will include professors Reva Siegel, Yale Law School; Frank Michelman, HLS; Richard Ford, Stanford Law School; Juan Perea, University of Florida Law School; visiting professor Molly McUsic, HLS; and David Wilkins, HLS.

“Brown v. Board of Education and Its Aftermath” – a series of lectures beginning Friday (April 16) at 4 p.m. – will also be held in Ames Courtroom. The series will begin with “Brown and the Montgomery Bus Boycott” by Fred Gray, attorney for Rosa Parks and the Rev. Martin Luther King Jr. “Prosecution of the Defendants of the 16th St. Baptist Church Bombing” by Doug Jones, the prosecuting attorney in this case, will follow. A keynote address titled “Reflections on Brown” by Dennis Archer, the current and first black president of the American Bar Association, will conclude the series.

“Looking Back: A Conversation With the Brown Lawyers – Reflections on Brown 50 Years Later” will be held Saturday (April 17) at 9 a.m. in the Austin North Room. The panelists include many of the lawyers involved in the Brown case litigation, including the Hon. Judge Constance Baker Motley, the Hon. Louis Pollak, attorney Oliver Hill, attorney Jack Greenberg, the Hon. Robert L. Carter, the Hon. Jack Weinstein, as well as children of the Brown lawyers, John Marshall, attorney Karen Hastie Williams, and Charles Hamilton Houston Jr.

“Looking Forward: Re-Argument of Brown with Current Issues – Resegregation, Justice, 25 Year Outline, the Harm of Integration on African Americans, and the Meaning of the 14th Amendment” will be held on Saturday (April 17) at 10:30 a.m. in the Austin North Room. This panel discussion will be co-moderated by HLS Dean Elena Kagan, and Professor Charles J. Ogletree Jr., vice dean of Clinical Programs at Harvard Law School. The discussion will include leading panelists in the fields of law, education, and economics from Harvard University, including Derek C. Bok, Professors Gary Orfield, Charles Willie, Randall Kennedy, Richard Parker, Kenneth Mack, Laurence Tribe, Caroline Hoxby, and one of the premier litigators in the United States, attorney John Payton.

April 21: Separate and Unequal: Segregation and Educational Opportunity in Metro Boston

An education research and policy conference hosted by the Civil Rights Project at Harvard University, this conference will examine segregation and educational opportunity in metro Boston. The conference will be held from 9:15 a.m. to 12:30 p.m. at the Harvard Graduate School of Education, Longfellow Hall in the Askwith Forum. Please note that although the event is free of charge, registration for the conference is required and the deadline is Friday (April 16). Online registration is strongly preferred.

April 22-24: 50 Years After Brown: What Has Been Accomplished and What Remains to Be Done?

Rod Paige, secretary of education, will deliver the keynote address – “Beyond Brown: Unfinished Business” – on April 22 at 8 p.m. in the John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum. Followed by a conference on April 23-24 in the Taubman Building. Hosted by the Program on Education in Policy and Governance.

April 26: A Commemoration of the 1954 U.S. Supreme Court Desgregation Order: Brown v. Board of Education

Hosted by the Harvard Foundation, the commemoration will feature a lecture and booksigning by Charles J. Ogletree Jr., Jesse Climenko Professor of Law. That’s in Fong Auditorium, Boylston Hall, from 5 to 7 p.m. Refreshments will be served.

Summers traced his personal and professional engagement with the legacy of Brown, from family discussions about the morality of his segregated Cub Scout troop to Harvard’s involvement in upholding the principles of desegregation and affirmative action in higher education. While decades have clarified and cemented the moral principles of desegregation, Summers said, the practical question of assuring equal and fair access to education remains a “defining challenge.”

‘Sober but never sullen’

Professor of Law Brewer, whose 1990 clerkship with Marshall came at the end of the Justice’s Supreme Court term (1967-91), described Marshall, the first black justice on the Supreme Court, as “always sober but never sullen.” “He seemed to me never to lose his passion for the law or for his work on the court,” said Brewer.

Brewer offered a critical perspective, half a century later, on the psychological data Marshall used to build his case that segregation harms the self-esteem of students of color.

Several former clerks commented on Marshall’s expansive view of justice that extended far beyond his best-known cases. Professor of Law Kennedy shared a conversation with Marshall in which he deemed his 1944 victory in the case of Smith v. Allwright, which overthrew the Democratic Party’s so-called “white primary” in Texas, as his proudest achievement.

“He was not a single-cause person,” said Fisher, the Hale and Dorr Professor of Intellectual Property Law. “He had a vision of what a decent society should be about.” Fisher said that Marshall was as committed to undermining gender discrimination as he was to eliminating racial discrimination, noting that the prominence of women on the HLS panel was no accident.

Minow, the Bloomberg Professor of Law, added that a review of Marshall’s dissents revealed that he had paid close attention to poor people, prisoners, minors, older people, rock music fans, people from Puerto Rico, persons with disabilities, anyone seeking an abortion, protesters, people with long hair, and racial minorities, among others.

“His capacity to put himself in the position of people quite unlike himself, I think, was unparalleled,” she said.

Whiskey, gambling, and good stories

Prompted by Kagan, the faculty members revealed some of their funniest memories of Marshall. The dean recalled Marshall calling her himself to offer the clerkship. When she said, “I’d love the job!” he responded, “What’s that? You already have a job?” The teasing continued for minutes until the Supreme Court justice took mercy on the young lawyer.

Minow interviewed with Marshall while suffering from a terrible cold. He suggested his father’s remedy to her: “You take quinine and whiskey. And then you leave out the quinine,” she said.

Wilkins, the Kirkland & Ellis Professor of Law, recalled an ill-fated gambling outing with his then-former boss during an American Bar Association meeting. Wilkins, who arrived at the casino without his wallet, borrowed money from Marshall, who shooed him away from the blackjack table for bringing bad luck. To Wilkins’ horror, he forgot about repaying the justice until a letter came to him at Harvard Law School; inside, Marshall had scrawled just one line: “Where’s my money?”

Wilkins and others recalled Marshall’s penchant for storytelling. “The stories were such an integral part of who he was and why he was such a great man,” said Wilkins. “He had such an eye for noticing details about people and for understanding the humanity of people.”

Minow shared one of Marshall’s favorite stories, not coincidentally about one of his favorite pastimes. A man went gambling in Las Vegas and lost so profoundly that he didn’t even have a quarter to open the coin-operated rest room door. Someone in the men’s room lent him a quarter, but he found that the previous occupant had left the rest room door open. So he gambled – successfully this time – with that quarter, invested his winnings, and grew very rich. He hired a private detective to find that man who launched his good fortune, but when the detective tracked down the men’s room lender, the now-wealthy man sent him away. He wanted to find the man who left the door open, he told the detective.

For Justice Marshall, said Minow, “It was about no handouts. Just leave the door open.”