Eye on China

Fairbank Center photo exhibit reveals human cost of nation’s rapid growth

“You go to China, it’s dazzling,” says Erik Eckholm, one of three contributors to an exhibit of photographs called “The Reporter’s Eye: Images from China’s Socioeconomic Frontiers.” “Tall buildings. Cars. Growing fast. But there are also all these casualties and cast-offs. I think it’s important not to forget them.”

Eckholm took up photography as an “intense hobby” when he was Beijing bureau chief for The New York Times from 1998 to 2003. He got the idea for a photo exhibit after he came to Harvard last year as a Nieman Fellow and connected with Pekka Mykkanen (also a Nieman Fellow, and former Asia bureau chief of Finland’s Helsingin Sanomat newspaper) and Hong Kong-based photographer Dermot Tatlow.

“I knew I had been thinking a lot about my pictures,” he says. “Then Pekka showed me some of the work he had done. I knew about this display space at the Fairbank Center and I asked them if they’d be interested in doing a group show …. They know me well. It came into the works without a lot of procedure. A phone call and an e-mail and (the staff said) ‘Yes, that would be great.’”

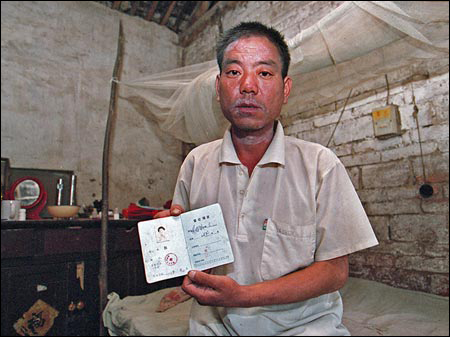

The pictures in the exhibit – which is, indeed, at Harvard’s Fairbank Center for East Asian Research, 625 Massachusetts Ave., in Central Square – are arresting precisely because the people in them seem so familiar. We’ve seen the elderly tourists shooting pictures in front of a faux palm tree before. They are our grandparents in Palm Beach, transplanted to Tiananmen Square. The soot-covered, stone-faced Chinese coal miner could just as well be from West Virginia. Through a rural town reduced to rubble, two young men ride bicycles that groan beneath the weight of bags full of scrap metal. Aren’t they the homeless folks from Central Square carrying empty cans and bottles to a liquor store for redemption?

Each photographer illustrates the transitions taking place in China differently. Eckholm took a particular interest in the lives of the migrant workers who take menial jobs and work long hours for dollars a day. He says that the money they make mostly gets sent back to dependent families in rural hometowns. Although the migrants have a hard life, Eckholm says they wouldn’t want to be portrayed as victims.

“I found fantastic spirit in the back alleys where people are living in old, crumbling houses,” he says. “Most of them are getting moved out now for high-rise apartment buildings in [China’s] version of urban renewal. You just find that people have a very good sense of humor…. These are the energetic strivers.”

Bursting with vivid reds and greens, Mykkanen’s photos often capture the dynamism of the “new” China: the rich young professional sitting poolside and smoking a big cigar; the owner of a trendy new restaurant where a cup of tea costs more than an average laborer earns in a day. Mykkanen says that, although rapid economic growth has made China an exciting place, it’s also turning the nation into a land of haves and have-nots.

“The pictures tell how extreme China has become,” he says. “[M]y picture of the couple by the swimming pool … was taken outside a five-star hotel where you pay $100 a night to stay [day laborers generally make $80 a week]. During the spring festival, the hotels are charging $300 a night and they’re all packed with tourists.”

Dermot Tatlow’s series of photos provide not only the starkest illustration of the wide divide that has opened up between rich and poor, but also the way in which the two groups are connected. A photo of a couple walking down a brilliantly lit Shanghai boulevard, for example, is literally surrounded by pictures of coal miners covered in dirt and soot, some seemingly on the verge of collapse from exhaustion. Tatlow says he was inspired to photograph the miners after tuning in to the news one day.

“CNN interrupted its regular programming for breaking news about the nine coal

‘The Reporter’s Eye: Images from China’s Socioeconomic Frontiers’ is on view at Harvard’s Fairbank Center for East Asian Research, 625 Massachusetts Ave. in Central Square, through May 31. Call (617) 495-4046 for more information.

miners who were trapped in a shaft in Pennsylvania,” he says. “At the same time in China, about 10,000 miners die every year in coal mines … . [The country’s] economic growth is underwritten by people working on extremely low wages, sometimes $50-$70 a month…. Wealth is certainly being generated, but the coal miners haven’t seen much of it.”

Mykkanen says that it’s important to understand the changes going on in China, not simply because the nation represents a fifth of the world’s population, but also because we’ll probably be meeting more people like those portrayed in the exhibit within the next 20 years.

“The World Tourism Organization estimates that 100 million Chinese will go overseas in 2020,” he explains. “That’s the combined population of Germany and the Scandinavian countries. You will see them in the casinos of Las Vegas. You will see them in front of John Harvard’s statue. And you will see them in small-time America when you see people standing around wondering ‘Where did all the jobs go?’”

For those already familiar with China, Eckholm says he thinks “The Reporter’s Eye” will still provide some “interesting looks” at a nation in transition. He seems particularly hopeful, though, that those who know little or nothing about the world’s most populous nation will see the exhibit.

“For people who aren’t familiar with China, … [the exhibit] shows a whole different side of things, good and bad, from what we normally hear about,” he says. “People can have very different circumstances, but it’s not hard to identify with them. There but for the grace of God go you. You can only wish that we could behave as well as they do under similar circumstances.”