Eggan works to increase transplant viability

Researcher forges ahead despite controversy

HARVARD STEM CELL INSTITUTE

Kevin Eggan is the kind of promising young researcher Harvard’s stem cell scientists are counting on for the future.

With the federal government restricting funding for stem cell research, they

Stem cell videos:

- Dr. Melton researches stem cells

- Dr. Scadden prescribes stem cell therapy

- HSCI hopes to accelerate research

- Dr. Scadden on embryonic stem cells

[default format for video is RealPlayer. For videos in Quicktime format, visit http://www.harvard.edu/multimedia/]

– More stories about stem cells

– Harvard Alumni Association videoconference on stem cells, “Unlocking the promise of stem cells”

– Harvard Stem Cell Institute hosts inaugural symposia (press release 4/23/04)

fear the Kevin Eggans of the world will opt to enter other fields, fields that aren’t in the center of a societal debate over its merits, fields where getting research funded is easier.

“What has been created is a real encumbrance on what is the hope of any field, and that is to bring the best and the brightest into it,” said David Scadden, professor of medicine and co-director of the new Harvard Stem Cell Institute.

Douglas Melton, the Thomas Dudley Cabot Professor of the Natural Sciences and the institute’s other co-director, said part of the institute’s mission is to create a community to welcome and encourage such young talent.

“I think this institute makes it possible for him to see a community of support,” Melton said.

Eggan agrees that support is important. In fact, Eggan said he came to Harvard’s Department of Molecular and Cellular Biology as a junior fellow last year hoping to find the resources to continue his research into somatic cell nuclear transfer begun as part of his doctoral studies at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology.

Eggan’s research, conducted primarily on mice, will hopefully one day lead to new therapies in which human patients will be able to get tissue and cell transplants without fear of rejection by their own immune system.

Today, when a patient gets a transplanted organ, their chances of survival are less because they have to take drugs to suppress their immune system so their bodies don’t attack the transplanted organ. A side effect of the drugs is that they leave the patient open to infections that their body might normally fight off.

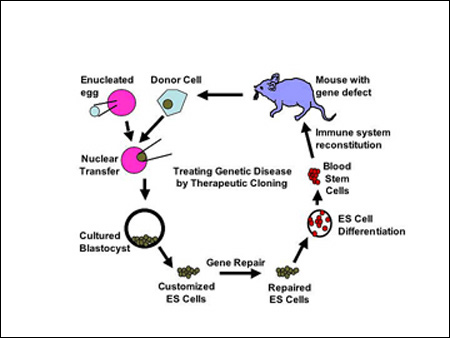

Somatic cell nuclear transfer, also called therapeutic cloning, involves taking the nucleus from an adult mouse cell and transplanting it into another mouse’s egg cell, which has had its nucleus removed. When that egg then begins dividing, it will create cells that are an exact match of the original animal’s cells.

As researchers understand how stem cells created through therapeutic cloning create different types of tissues, they hope to be able to control that process – in both mice and humans. One day researchers hope to be able to direct human stem cells to generate liver tissue, for example, for a patient with liver disease.

The advantage over traditional transplant techniques is that the cloned liver tissue would be an exact match for the patient’s own tissue. That means the body would accept it as its own and not fight it as foreign tissue.

Eggan’s particular work is focused on understanding how the transplanted nucleus functions. Tissue cells, he said, are very dedicated to being those tissue cells. Liver cells, for example, can’t be transformed into any other type of cell. But if a liver cell nucleus is transplanted into an egg cell, suddenly that nucleus is able to direct the creation of every tissue in the body.

Eggan said his work is also valuable as a way to create laboratory models of diseases, currently by growing tissue from animals with a particular disease to study how the disease develops under controlled conditions. Those same models can be used to test different drugs and treatments.

“I’m hoping this stem cell institute will provide the opportunity to do research that the federal government won’t fund,” Eggan said. “I think one has to ask oneself if an area is important enough to pursue even if that field doesn’t get federal funds.”

Should Eggan’s research reach a point where it needed private support, at least some donors are standing by to help. Howard Heffron, a member of Harvard Law School’s Class of 1951, is among the initial donors for the institute and is sending a message to young scientists.

“The message is that private money is coming. It’s here and it’s coming,” Heffron said. “It’s too damn important to walk away from.”