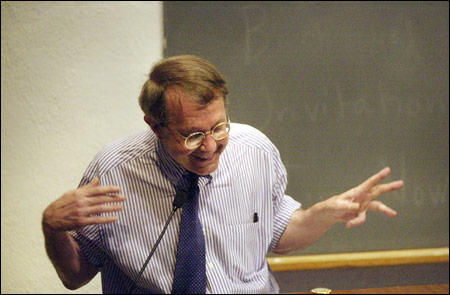

Educator, reformer Kozol speaks at the Divinity School

Sharply critical of public school financing, high-stakes tests

The children who inhabit the world of award-winning author, educator, and activist Jonathan Kozol ’58 don’t wear designer clothing, don’t have parents who drive around in SUVs, and don’t vacation at Disney World. They live in extreme poverty in the inner cities in places like New York and Los Angeles and often endure chronic asthma, hunger, and homelessness as a way of life. For 40 years, Kozol has worked with these poor children, their parents, preachers, teachers, and principals – and spoken out against the inequities of this country’s public school systems.

On April 13, Kozol visited the Harvard Divinity School (HDS), “a sort of second home,” to participate in “Conversations With Jonathan Kozol.” The program was co-sponsored by the Office of Ministerial Studies and the Program in Religion and Secondary Education (PRSE).

After welcoming remarks by Diane L. Moore, M.Div. ’84, a lecturer in religion and education and the director of the PRSE, the Rev. Claudia A. Highbaugh introduced Kozol. Highbaugh, chaplain, associate director of ministerial studies at HDS, and member of the Faculty of Divinity, explained, “I heard Jonathan speak for the first time 17 years ago. I listened carefully to his presentation and learned that I likely needed to be finding a place for other people – little people – not me. I’ve changed my own ethical point of view to base my work, vocation, ministry, educational pedagogy – all of this on the uplift of all children. When you leave today, don’t leave just inspired. Keep your mind, spirit, passion, attention, energy, and good work attuned to the children. Ye who have ears, let them hear.”

And there was plenty to hear from Kozol, a summa cum laude graduate with a degree in English literature and the recipient of a Rhodes Scholarship to Oxford, two Guggenheim Fellowships, and two Rockefeller Foundation fellowships.

According to Kozol, he was making plans in 1964 to go to graduate school and eventually teach literature, when his life changed forever with the disappearance and murder of three young people who came to Philadelphia, Miss., to help break the back of Southern apartheid.

“I took the T to Roxbury, walked into an AME church, and asked the pastor if I could be of use,” said Kozol. “I taught reading that summer and ran a rent strike for black tenants. I kept the rent money in my sock.”

That fall, deciding he wanted to be a real teacher, Kozol walked into the Boston Public Schools. (“If you’re willing to teach in a segregated school in America, you can almost always get a job,” he said.) He became a substitute teacher in the fourth grade in a Roxbury school that was technically in Dorchester.

“If I wasn’t political when I started, I was by the end of that year,” he said. “In one way or another, I’ve been working with poor black and Latino kids ever since.”

Kozol documented his first year as a teacher in “Death at an Early Age: The Destruction of the Hearts and Minds of Negro Children in the Boston Public Schools” (1967) and won the National Book Award in 1968.

Kozol spoke eloquently about the state of America’s public school system. He noted, “We say in church and in synagogue that all children are of equal value in the eyes of God, but not in the eyes of the United States. Because of the antiquated and undemocratic way by which we finance public schools, our children come into the public classroom with a price tag on their foreheads. My children in the South Bronx are cheap children; they are $8,000 babies. In a typical suburb, they’d get $12,000 worth of education per year; in the richest suburb, $18,000. This is a theological abomination. It’s obviously evil, and I don’t know why our preachers don’t talk about it with anger in their voices.”

Kozol also believes that “it’s outrageous to impose high-stakes tests on children in early grades of school if we first deny them an opportunity for pre-K school. There’s something hypocritical in a society that holds 8- and 9-year-olds ‘accountable’ for their performances on a standardized exam, but doesn’t hold the president and other high government officials accountable for robbing them of what they gave their own children five years earlier. I’m not against testing, but there’s something unhealthy about the form that high-stakes testing has taken in the past five years.”

A proponent of quality pre-K for every child starting at age 2 1/2, Kozol said, “Opponents always bring up the other problems. They are pointing to things they can’t change in order to avoid paying for one thing they could change. This is the worst possible intellectual trap. No matter what other problems poor children have, it would be great for them to have two or three years of happiness. Is this nation not wealthy enough? We could provide rich, wonderful pre-K to all the poor children in our country for three years for what we spend in Iraq in three weeks.”

Many of the students in the audience plan to become teachers. Kozol noted that “nothing in public schools is as important as the quality of the teachers. Especially in the inner-city schools, I see wonderful teachers who feel besieged, beaten down by punitive demands from Washington. They quit because they lose all the pleasure of authentic learning. They have to marshal the students into examination soldiers.”

A close friend of the late Fred Rogers, the “ultimate teacher,” Kozol noted, “Wouldn’t it be a different country if he had been the secretary of education? Try to keep alive his tender legacy.”

Kozol has written other books based on his experiences among the poor, including “Rachel and Her Children: Homeless Families in America” (1988); “Amazing Grace: The Lives of Children and the Conscience of a Nation” (1995); and “Ordinary Resurrections: Children in the Years of Hope” (2000).