When the fog clears

‘The major lesson of the Cuban missile crisis was that the combination of human fallibility and nuclear weapons will destroy nations’

Learn from your mistakes. Pass the lessons on to those who may face similar problems in the future. And don’t be afraid to challenge authority.

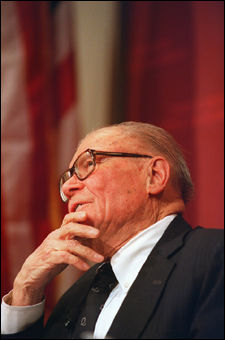

This, in essence, was the message Robert S. McNamara brought to the Kennedy

School’s John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum Wednesday (March 3). Now a forceful and peripatetic 87-year-old, McNamara has served as president of Ford Motor Co., U.S. secretary of defense, and president of the World Bank. He is also a prolific author.

The presentation was titled “The Fog of War: Eleven Lessons From the Life of Robert S. McNamara,” which also happens to be the title of an Academy Award-winning documentary film by Errol Morris, now in theaters. Moderator Graham T. Allison Jr., director of the Kennedy School’s Belfer Center for Science and International Affairs, showed clips of the film (which consists of a lengthy and remarkably frank interview with McNamara supplemented by archival footage), then asked the former Cabinet member questions based on what had been shown.

Also sharing the stage was Ernest May, the Charles Warren Professor of American History, who worked with McNamara on a book about the Cuban missile crisis (“The Kennedy Tapes: Inside the White House During the Cuban Missile Crisis,” edited by May and Philip Zelikow).

“The major lesson of the Cuban missile crisis was that the combination of human fallibility and nuclear weapons will destroy nations,” McNamara warned in the first clip.

He emphasized this point with a terrifying story about an interview he had with Fidel Castro in 1992 in which the Cuban leader revealed that there had been 162 Russian nuclear warheads on the island at the time of the crisis. McNamara asked Castro whether he knew this, and he replied that he had.

“Did you recommend that the Russians use them?” McNamara had asked.

“Yes, I did,” Castro said.

“And what would have happened to Cuba?”

“It would have been totally destroyed.”

When Allison, who called the crisis “the most dangerous moment in human history,” asked McNamara what it had taught him about nuclear weapons, his reply was straightforward: “Get rid of them!”

During the crisis, McNamara had urged caution and was responsible for restraining those who wanted to use force against the Russians.

“He was the person holding everybody back by saying, Let’s think hard about it,” said May. “It’s a marvelous example of someone having a cautionary effect on policy-making.”

Later in the discussion, McNamara shared credit for defusing the crisis with

another adviser to the president – Llewellyn Thompson, who had been ambassador to the Soviet Union and knew Nikita Khrushchev well. The White House had received two messages from Khrushchev, one “hard” and one “soft.” While most of Kennedy’s advisers agreed he should reply to the hard message, Thompson took a different position.

“Thompson said, ‘Don’t respond to the hard message. You’d be wrong, Mr. President.’ That takes guts.”

McNamara added that during the Vietnam War, there were no advisers with the same sophisticated understanding of the enemy that Thompson had shown. The lack of what McNamara called “empathy” for the Vietnamese resulted in a basic misconception about the conflict.

“The Vietnamese saw us as replacements for the French. They thought we were fighting a colonial war, which was absurd. We saw the Vietnam conflict as an aspect of the Cold War, but they saw it as a civil war.”

McNamara related several incidents that showed how difficult it was even for expert opinion to stop the juggernaut of foreign policy once the government had committed itself to defeating communism in Southeast Asia.

While doing research for his book “In Retrospect” (1995), which deals with his role in the Vietnam War, he discovered a 1967 memo from then-CIA Director Richard Helms.

“Helms said if we leave Vietnam in defeat, our security will not be adversely affected. All the security analysts at the time agreed, but you can’t even find references to that memo today.”

In the same year, McNamara himself wrote a memo to Lyndon Johnson recommending that the United States pull out of Vietnam. In response, Johnson called together the most senior and respected experts in foreign and defense policy and asked them to draft a report on the question.

“Their conclusion was the opposite – go on as before. I was the only senior official to hold the views I did, and I thought that memo was the best thing I had ever written.”

McNamara believes that there are even fewer people in government today who are equipped to understand the thinking and motivation of our enemies. He said that the single most dismaying line in the 840-page transcript of the congressional hearings on 9/11 was when an authority on education in the United States was asked how many undergraduate degrees in Arabic had been awarded in the previous year. The answer was eight.

In the film, McNamara does not comment directly on the war in Iraq, although in one clip he does make a strong statement regarding unilateral action in foreign affairs.

“If we can’t persuade nations with comparable values of the justice of our cause, we’d better re-examine our reasoning.”

Asked to comment further on this issue, he said that he has refrained from speaking publicly about the actions of the Bush administration because he feels it would be inappropriate for a former secretary of defense to comment on ongoing military operations. But he left no doubt in the minds of the audience where he stands on the war, eliciting a burst of applause when he invited them to draw their own conclusions.

“If you think there’s something you just heard that applies – apply it!”

Toward the end of the presentation, McNamara exhorted his audience, composed largely of Kennedy School students and undergraduates, not to shrink from confrontation and debate when or if they found themselves in the position of decision makers.

“For God’s sake, force your associates to surface divisive issues. This was not done in the Ford Motor Co., and it was not done in the State Department. It’s very difficult to do, to force people whom you respect and love to come into conflict.”

McNamara said that if the domino theory, the basis of U.S. policy in Southeast Asia, had been properly debated, the Vietnam War would not have continued as long as it did. He said that currently there is too little debate in government about nuclear weapons policy or about military spending.

He also urged his audience of future leaders to be open about their mistakes so that others can benefit from their experience.

“You should feel an obligation to identify your mistakes. You shouldn’t wait until you’re 87!”