The great debate

On March 19, 1919, the future of the world hung on an academic discussion

The strained relationship between the United States and the United Nations has often dominated headlines. The U.S., as the world’s most powerful nation, is the international peacekeeping body’s biggest supporter and its largest detractor – a riddle that has long puzzled politicians, journalists, academics, and the general public.

The underlying tensions go way back – further, in fact, than the United Nations’ founding in 1945, back to 1919, when the U.S. government became deeply divided over whether the United States should join the League of Nations, the UN’s

forerunner.

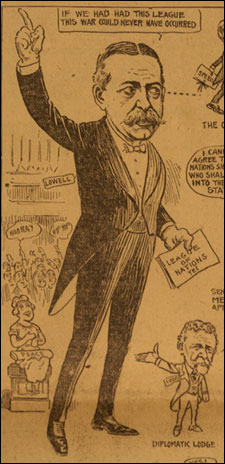

Eighty-five years ago, on March 19, 1919, two Boston Brahmins who were among the most distinguished intellectuals of their age publicly debated U.S. entry into the League of Nations. Harvard University President A. Lawrence Lowell, a Harvard-trained lawyer and government scholar, argued in favor of joining the league, while U.S. Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, a Harvard-trained lawyer, historian, and editor, argued against.

That two men with such similar backgrounds could have such different views intrigued the world; the issues they first raised inform today’s arguments. The Lodge vs. Lowell Debate stands as a reminder both of how much personalities influence history and of how clashes between opposing ideals reverberate across generations.

A collision course

Perhaps the best place to begin is Nov. 11, 1918: Armistice Day, when what was hopefully called the War to End All Wars ended. We now know the conflict as World War I and Nov. 11 as Veterans Day, but at that moment, people across the world were jubilant that the bloodiest war in history was over. A Library of Congress Web site recalls the scene in Boston as described by shoemaker James Hughes: “. . . some of them old fellas was walkin’ on the streets with open Bibles in their hands. All the shops were shut down. I never seen the people so crazy … confetti was a-flying in all directions.”

While the people celebrated, trouble was brewing in Washington. U.S. President Woodrow Wilson – a lawyer, government scholar, and former president of Princeton University – had advocated a “peace without victory” because “only a peace among equals can last.” U.S. Sen. Henry Cabot Lodge, Republican of Massachusetts, denounced the Democratic president’s call for a “soft peace”; as his official Senate biography puts it, Lodge “found Germany completely responsible for the war in Europe and demanded the unconditional surrender of the Central Powers.”

Wilson made two fateful choices: He decided to personally attend the peace talks in Paris, and he decided not to include any Republican senators in the American delegation. The second decision would cause the president much grief, since the

Nov. 5 election of just a week before had put Republicans, led by Lodge, in control of the Senate, and under the U.S. Constitution the Senate has sole power to approve treaties.

Wilson’s vision of a lasting peace, guaranteed by a League of Nations, was wildly popular with the crowds he addressed in Europe, and creation of such a league became part of the negotiated peace treaty. The draft Covenant of the League of Nations was completed in Paris on Feb. 14, 1919, and Wilson sailed aboard the George Washington for America, landing in Boston on Feb. 24, where he was again met by cheering crowds in what Lodge defiantly characterized as “my own city.”

On Feb. 28, Lodge began a campaign against the league. As a Senate Web site notes, Wilson and Lodge “had disliked one another for years. Among the first to earn doctoral degrees from the nation’s newly established graduate schools, each man considered himself the country’s pre-eminent scholar in politics and scorned the other.”

The idea of an international league was hardly new; Lodge would note, “they go back to the days of Greece.” Lodge himself had long been in favor of such a body, but he didn’t like the League of Nations as described in the covenant, and he didn’t like the fact that Wilson had treated the Senate with contempt. The bitter relationship between the two most powerful politicians in the country would become, according to the Senate Web site, “one of the most turbulent in U.S. history.”

A moderating influence

Harvard President Lowell decided to jump into the fray as a nonpartisan, moderating influence by challenging Lodge to a public debate. Chairman of the

Download the full text of the Lodge vs. Lowell Debate as a PDF

Hear Sen. Lodge speak about the League of Nations

Hear President Lowell’s 1932 address about the Japanese invasion of Manchuria

For more about Wilson and Lodge, see ‘A Bitter Rejection’ at the U.S. Senate’s Web site.

See Wilson’s White House biography

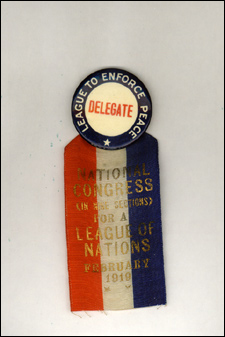

executive committee of the League to Enforce Peace, which supported the idea of a League of Nations, Lowell saw a clear need for mediation. He carried on a steady stream of correspondence about the issue, now contained in the Harvard University Archives.

On March 11, Lowell wrote, “The prospect of the league has been seriously injured by pride and temper on both sides. My hope is, in the debate with Mr. Lodge, to raise it to a higher level of public spirit.”

On March 12: “I feel as if I had challenged the biggest figure I could find, the leader of the Republican opposition. … I feel also that I have the advantage of being able to state clearly what we want; and so far he has not felt that he could state exactly what he wanted, because he really wants a League of Nations of some kind, but has not said what.”

And on March 19, just hours before the debate itself: “… my task does not concern what President Wilson has or has not done; but whether the country should accept the Covenant of Paris, with such amendments as may be suitable.”

Worldwide interest

If Wilson and Lowell shared similar academic and political backgrounds, the ties between Lowell and Lodge were so strong that to say they were cut from the same cloth – the very fabric of Boston – is something of an understatement.

Their families had achieved wealth and power in colonial days. Lodge was Harvard A.B. 1871, LL.B. 1874, Ph.D. (history) 1876, LL.D. (honorary) 1904; in 1919 he was a year into his third six-year term on the University Board of Overseers.

Lowell was Harvard A.B. 1877, LL.B. 1880, in his 10th year as Harvard president, and like Lodge, a Republican, though an independent one.

But as the Chicago Tribune pointed out, “President Lowell represents the pure student and theorist … [while] Senator Lodge, by comparison, represents the practical and realistic. It is true he is himself a historian of note … . But in addition, while President Lowell has been studying the science of government, Senator Lodge has been practicing it.”

A contest between two such adversaries proved irresistible. The Boston Evening Transcript for March 14 reported that more than 50,000 people had sought tickets; “The demand … is greater probably than was ever before manifested in connection with an event of the kind and indicates the general sentiment that the debate will be one of the most significant in the history of the country.” By March 19, more than 72,000 ticket applications had been received.

The great debate

Some 4,000 people crowded into Symphony Hall the evening of March 19. “And it was an exceptional audience of representative citizens,” wrote A.J. Philpott of The Boston Evening Globe. “All classes and kinds of people were in it, and no one class seemed to dominate. There were politicians, leading men of affairs, judges, Legislators, Governmental officials of all kinds, professional men and a whole lot of the plain people – and there were probably 1,000 women. Every foot of sitting room on stage, floor and balconies was occupied, and more than 1,000 stood up along the ‘side lines.’”

Newspaper reporters from around the globe crowded the front rows. “Telegraph instruments were installed almost under the noses of the speakers,” Philpott wrote, “and the remarks were put on the wires as fast as delivered, for it was a debate in which the whole world was interested.”

The concert hall was decorated with a single large American flag at the rear of the stage, an unusually sedate display. An organist entertained the waiting crowd, who sang along with such favorites as “Onward Christian Soldiers.” When the debaters appeared about 10 minutes after 8 p.m., the audience stood and sang “The Star-Spangled Banner.”

Massachusetts Gov. Calvin Coolidge – soon to be vice president and then

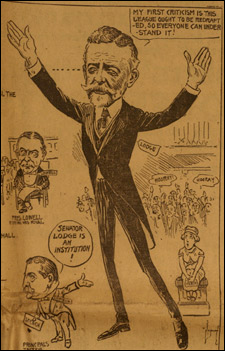

president – moderated. “Silent Cal,” true to his nickname, said little; under the terms of the debate, Lodge would speak for an hour, Lowell for an hour-and-a-half, and Lodge had a half-hour for rebuttal. The debaters were elaborately cordial to one another, with Lodge saying of Lowell that “he and I are friends of many years” and Lowell declaring he regarded Lodge “not merely as a statesman but as an institution.”

The heart of the matter

Before the debate, one Boston newswriter had described the difference in the two men’s positions as the difference between “a” and “the.”

Lodge supported a league; as he put it, “I am anxious to have the nations, the free nations of the world, united in a league … to do all that can be done to secure the future peace of the world and to bring about a general disarmament.”

But Lodge did not support the league as described in the covenant, which he declared “to have been very loosely and obscurely drawn.” He also lamented that the covenant was part of the peace treaty because debate on the league delayed treaty approval.

Lodge specifically faulted the covenant for:

- Increasing the contact between nations, because “Wars between nations come from contacts.”

- Interfering with the Monroe Doctrine that asserts U.S. interest in the Americas, noting that had the league been established in 1898 the United States “could not have interfered and rescued Cuba from the clutches of Spain.”

- Mandating that the United States become involved in “every obscure quarrel that may spring up in the Balkans.”

- Opening the door to uncontrolled immigration. “There should be no possible jurisdiction over the power which defends this country from a flood of Japanese, Chinese, and Hindu labor.”

- Not containing language for any country to leave the league.

- And most importantly, for Article X, which pledged every member state to guarantee other nations’ safety against aggression. “I ask those – the fathers and the mothers, the sisters and the wives and the sweethearts – whether they are ready yet to guarantee the political independence and territorial integrity of every nation on earth against external aggression, and to send the hope of their families, the hope of the nation, the best of our youth, forth into the world on that errand?” Lodge said.A man in the audience answered “Yes,” but many voices shouted “No, no, no!”In his closing remarks, Lodge evoked national pride, declaring “I am an American – born here, lived here, shall die here. I have never had but one flag, never loved but one flag. I am too old to try to love another, an international flag.”

When it came his turn, Lowell took a much more analytical, professorial approach, declaring he was in favor of the league, though with amendments. “We both feel that this covenant is, as it stands, defective, but the difference is that I feel that when those defects have been removed, that covenant … ought to be ratified.”

The college president noted that contacts minimize friction rather than create it. “We try to encourage men traveling in other countries … Why? Because it bridges points of contact and therefore points of friction. Because it makes people understand one another and tends on the whole to the peace of the world.”

Lowell also addressed Lodge’s main point – that joining the league would necessitate sending American soldiers abroad – by saying if every nation agreed to go to war against an aggressive country, no country would dare to be aggressive.

Much of Lowell’s talk involved what was actually written in the covenant. “… I shall have to weary your patience a little,” he told his audience, “by going through that document … and I will ask you to listen patiently, because the whole question of what we are to do depends upon what we actually agree to do.”

But in every debate there are surprises, and Lowell provided the biggest one.

(From the personal collection of John Lenger) Opponents of the league, including Lodge, often invoked Washington’s Farewell Address, which warned against “permanent alliances with any portion of the foreign world.” Lowell thought the notion was outdated, and said so, declaring, “That Farewell Address was one of the greatest documents ever made in its day – and so were the Ten Commandments.”

As he later would write, “I do not know why I made, on the spur of the moment, the remark about the Ten Commandments. Of course I did not mean that they had become in any way obsolete. No allusion to the Ten Commandments appeared in my speech as I prepared it beforehand, or in the revised edition which has since been published with my authority.” But the full text of the debate was reprinted and widely distributed within hours, and Lowell was criticized for his remarks about the Ten Commandments and about Washington’s Farewell Address. More than six months later, U.S. Sen. William E. Borah of Idaho would condemn Lowell for his debate stance and for “the cold indifference, the ill-concealed contempt for everything American found throughout his writings.”

Many praised Lowell, however, including Philpott of the Globe, who wrote that “Frankly, Pres. Lowell surprised his auditors. They did not expect him to loom up the way he did against the senior Senator, especially in a matter pertaining to foreign relations, of which Senator Lodge is past master.”

Lodge biographer Karl Schriftgiesser summed up the debate result:

“Newspaper polls taken after the meeting indicated that opinion was almost equally divided. Most of the press felt that both Lodge and Lowell were in near enough agreement so that the two schools of thought could easily iron out their differences and insure adoption of the League.

“Calvin Coolidge said, ‘Both men won.’”

The aftermath

As Philpott wrote, “The great debate – the greatest staged in this country in 50 years – on the most momentous question before the world today, the League of Nations, took place in Symphony Hall last night. … However, it is doubtful if anybody went home changed very much in his views. The change comes as a rule when men sit down and read the argument in cold blood.”

Yet that cold-blooded deliberation didn’t happen, of course. The battle between Wilson and Lodge became ever more heated and bitter. Wilson took his case to the American people on a cross-country speaking tour that exhausted him. On Oct. 2, he suffered an incapacitating stroke. On Nov. 19, the Senate for the first time in its history rejected a peace treaty by failing to approve the Paris covenant that included the League of Nations. Wilson was awarded the Nobel Prize for Peace in 1919 but was too ill to travel to receive it. The U.S. president became known as the father of the League of Nations but the United States never joined. Wilson finished his last year in office as a near recluse and retired from public life, dying on Feb. 3, 1924; his widow wrote to Lodge asking him not to come to the funeral.

Lodge himself died on Nov. 9, 1924. According to his Senate biography, “even in memorials praising his achievements, bitterness over the League fight remained. Indeed, a Massachusetts obituary writer spoke for many when he wrote of Lodge, ‘He was not loved, as a general rule; but he was respected for courage and large ability. He was a force – greatly dangerous or greatly helpful, as the view went – as well as a figure.’” Lodge’s own take on the league debate, “The Senate and the League of Nations,” was published posthumously in 1925.

Lowell outlived both Wilson and Lodge by many years; he continued championing the cause of international cooperation. In a radio address recorded Feb. 17, 1932, Lowell urged the United States to support whatever efforts the League of Nations made to sanction Japan for invading Manchuria. “Not only the progress of this conflict, but also the future attitude of the world about war, may well depend upon our decision,” he said.

Lowell, ever the educator, even turned the League of Nations debate into a civics lesson. In his book “What a University President Has Learned,” Lowell wrote: “… many a man has failed to execute an otherwise carefully prepared plan by not perceiving its true essence, and by insisting on some detail not of primary significance … . That seems to have been true of President Wilson’s unwillingness to accept the reservations to the League of Nations … . As one looks back on them they appear harmless, but President Wilson insisted that the measure should be accepted as he submitted it. Had he directed his followers to vote for the Treaty with the reservations it would have been ratified by an enormous majority. It was then too late for Senator Lodge to propose further changes … . Wilson’s error was a characteristic defect of an otherwise powerful intelligence and brilliant imagination. Whether the success of the League was seriously affected by the absence of the United States, whether our presence would or would not have stiffened its policy, and made its members more ready to carry out their obligations in regard to sanctions and the use of force, are questions upon which opinions may differ, and need not be discussed here.”

“What a University President Has Learned” was published in 1938. In 1939, World War II began in Europe; the United States joined the fighting in 1941. Lowell died in 1943, at age 86, as war raged across the globe. Two years later the United Nations would be founded in the aftermath of World War II.