Portrait of the artist as molecule

Sackler exhibits Gary Schneider’s intimately scaled photographs

During the early 1980s, artist Gary Schneider, at a creative impasse in his own work and faced with the necessity of earning a living, decided to capitalize on his darkroom skills and set himself up in business as a printer of the work of other photographers.

The experience of printing photographs by a diverse group of artists that included Richard Avedon, Irving Penn, Nan Goldin, and Lisette Model, as well as the photos in Madonna’s book, “SEX,” honed Schneider’s technical skills and prepared him for a new phase of his career that would bring him widespread recognition and acclaim.

Although he had been influenced early in his career by conceptual art and performance art, which often radically de-emphasize the importance of the art

object itself, Schneider’s experience as a professional printer crystallized his interest in producing photographs that could stand alone as powerful and compelling artifacts.

Schneider’s first retrospective exhibition is now on display at the Sackler Museum. Curated by Deborah Martin Kao, the Richard L. Menschel Curator of Photography at the Harvard University Art Museums (HUAM), the exhibition encompasses a 25-year period, from the artist’s early fragmented portrait photographs to his “Genetic Self-Portrait” of the late 1990s, a series of works that has toured widely and elicited much critical attention.

“I wanted to do an exhibition on a photographer whose work was important and intersected with many of the large ideas in contemporary art, but who was not yet a household name,” said Kao.

“Portrait of Ralph” and “Assisted Self-Portrait,” done when Schneider was a 20-year-old art student in his native South Africa, already show the artist’s interest in creating photographs that compel the viewer’s attention through their aesthetic quality as well as their content. These portraits take the novel approach of presenting their subjects as a series of discrete body parts, shown approximately life-size. Insofar as they display fragments but withhold the totality, they also embody a characteristic tension between disclosure and concealment.

“Carte de Visite,” a series of photographs Schneider produced in 1990, reflects the artistic possibilities he discovered working as a master printer. During

this time he began to collect 19th century negatives, acquiring thousands of them at garage sales, second-hand stores, and flea markets. Among these was a collection of tiny glass negatives that Schneider bought in New York City in 1989. They showed young women of the Victorian era confronting the camera with unsmiling formality.

Schneider created large format prints from nine of these negatives (five are displayed in the Sackler exhibition) that bring the women to life with startling immediacy. What is responsible for this impact, Schneider believes, is that the women show no trace of the “camera face” that people of our time automatically assume when they know they are having their pictures taken. Working with these photographs led him to seek ways of making portraits of contemporary subjects that would break through habits of conventional self-presentation.

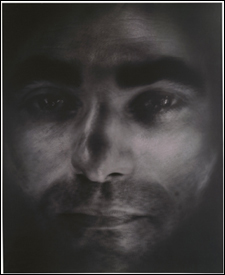

The technique he came up with was the durational portrait. Taking his cue from the long exposures 19th century photographers used, Schneider went them one better by using exposures of as much as an hour. Instead of immobilizing his subjects with a head brace as earlier photographers had done, Schneider has them lie supine on the floor of his studio, making them comfortable with cushions and pillows. His large format camera is positioned above their heads.

He then turns out the lights, opens the camera shutter, and projects a beam from a small flashlight, section by section across the subject’s face. This process provides the light source by which the image is recorded on film.

While the exposure is being made, the photographer and his subject are interacting in a close, intimate manner, and the portrait becomes a record of this interaction. The subject’s movements and changes in expression, the fact that different parts of the face have been exposed at different times, create distortions in the final image.

“You probably wouldn’t recognize the actual person. They’re not about mapping the subject’s outward appearance,” said Kao.

Enlarged to more than twice life-size, these otherworldly portraits have an intense and overwhelming impact, forcing the viewer to interact with the image.

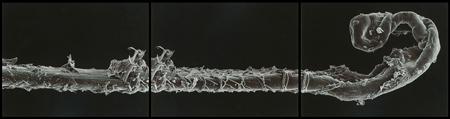

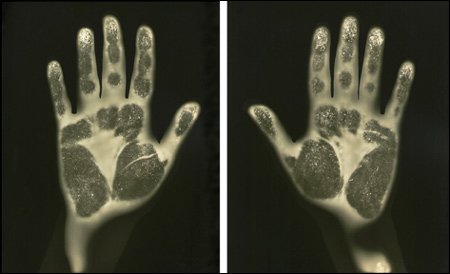

Schneider’s “Genetic Self-Portrait” came about when he was invited to create an artistic response to the Human Genome Project. He spent 18 months working with scientists at Columbia-Presbyterian Medical Center in New York to create a series of photographs based on parts of his own body. The final result is not unlike his early fragmented portraits, except that the state-of-the-art imaging technology he uses allows him to reveal himself at increasingly microscopic levels. The conventional likeness of the “actual” Gary Schneider, however, remains undisclosed.

The series includes monstrously enlarged photos of Schneider’s irises, retinas, hair, intestinal flora, mucosa cells, chromosomes, sperm, and DNA. The photographs function both pictorially and scientifically – as both valid laboratory data and evocative images of great beauty and power.

“People will see them very differently depending on what they bring to them,” said Kao.