Kay: Intelligence failure, not deception, led to war

Former weapons inspector says Iraq is better off now

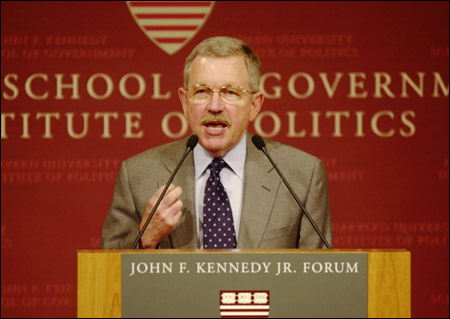

Former U.S. weapons inspector David Kay called it “a damning charge” against Western democracy that it took the fear of horrific weapons of mass destruction to move the world to act against the corrupt, murderous regime of Iraqi leader Saddam Hussein.

In his talk to a packed forum at the John F. Kennedy School of Government, Kay detailed Hussein’s influence on Iraq by its body count: between 400,000 and a million of his own citizens killed, and another million more in the Iran-Iraq war. Despite the physical horrors of Hussein’s reign, however, Kay said perhaps the most lasting effect will be the destruction of Iraq’s civil society through decades of fear and corruption.

“We moved against Iraq for what turned out to be the wrong reason and it’s probably the only reason that would have gotten international action,” said Kay, who spoke at the Kennedy School’s John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum Monday (March 22). “That is a damning charge against Western democracy which we deserve to think about long and hard.”

Though the fear of chemical, biological, and nuclear weapons spurred the United States’ action, Kay reiterated earlier assertions that there were no such weapons programs. Despite international agreement that Iraq was lying about its weapons programs, despite detailed knowledge of such programs in the 1980s and early 1990s, the Iraqis in this case, he said, were telling the truth.

“We went to war because of the expectations that there were large stockpiles of weapons. There were no weapons stockpiles there,” Kay said. “We got so used to Iraq trying to limit inspectors, to lie, cheat, and deceive, that we got into the mind-set that Iraqis would only lie, cheat, and deceive. UN inspectors ceased to believe that Iraq would ever tell the truth.”

Kay’s talk, “Iraq, WMD: Lessons Learned and Unlearned,” was sponsored by the Institute of Politics (IOP). Kay, who was introduced by IOP Director Dan Glickman and by Kennedy School Dean Joseph S. Nye, served as chief U.S. weapons inspector in Iraq from June 2003 until January 2004. Previously, he served as chief nuclear weapons inspector for the United Nations after the Gulf War and was held by Saddam Hussein on one occasion for four days in a Baghdad parking lot before being released.

Though the weapons threat that underpinned the U.S. war in Iraq was nonexistent, Kay didn’t blame the Bush administration alone. After reviewing intelligence reports from many nations, Kay said France, Germany, and other nations were also convinced that Hussein had clandestine weapons programs.

Further, Kay said, Hussein behaved as if he had those programs.

The failure was one of intelligence, of relying on sophisticated satellite photographs instead of people on the ground. Though technology can greatly aid in spying, Kay said, what it misses is the thoughts and intentions of people in power.

“What you really need to know, you’re not going to learn from space,” Kay said.

In the case of Iraq, Kay said, what was missed was that the reason for Hussein’s behavior with regards to weapons of mass destruction changed in the early to mid-1990s. Instead of having those weapons, Kay said, Hussein behaved as if he did in order to suppress domestic enemies among the Kurds in the north, whom Hussein had gassed, and the Shiites in the south, whom Hussein had brutalized when they rose up in Basra.

To suppress those restive populations, Kay said, Hussein merely had to act as if he possessed the weapons he had in the past. The Iraqi public knew from harsh experience that if he had them, he would have no qualms about using them.

“What we failed to see is that consistency of behavior is not the same as consistency for the reasons behind the behavior,” Kay said. “His rationale changed and we missed it.”

To make matters worse, Kay said, when inspectors were withdrawn from Iraq, the United States had no agents there, making it even more difficult to divine what was happening.

In addition to misinterpreting Saddam Hussein’s behavior, Kay said the United States and other Western nations missed the disintegration of Iraq’s society, both of its physical infrastructure and of its ability to function normally, due to fear, poverty, and corruption. Iraq wasn’t capable at that stage, Kay said, of launching a major arms program.

The depths of that collapse are now part of the difficulty facing U.S. administrators as they try to rebuild Iraq.

“If we had understood how bad Iraq had become, we wouldn’t have argued they had resurrected a large weapons infrastructure,” Kay said.

The intelligence missteps led not only to the Iraq war, Kay said, but also to an erosion of American credibility that has ramifications far beyond Iraq.

Unless the Bush administration admits the mistakes that were made, Kay said, its ability to handle other international crises – such as those today in North Korea and Iran – will be greatly diminished. Already, Kay said, North Koreans and Iranians are casting doubt on U.S. claims about their weapons programs, citing U.S. errors in Iraq.

At home, Kay said, people who had opposed the war are angry and bitter because they believe they’ve been lied to by the Bush administration.

Though weapons claims were in error, Kay said he does not believe the Bush administration manufactured or manipulated evidence to make the case for war. Kay said he thinks administration officials were genuine in their belief about the threat Iraq posed, and, in the wake of 9/11, were unwilling to give Hussein the benefit of the doubt.

Though no weapons of mass destruction were found, Iraq did pose an increasing threat. It had the ability to procure weapons systems, such as long-range missiles, and was so corrupt that it wouldn’t have refrained from selling weapons to a high bidder internationally.

Kay concluded that Iraq is ultimately better off for the U.S. intervention.

“If you spend any time in Iraq today, you can’t help but say, when asked the question whether the war was worth it, that the Iraqi people are far better off without Saddam Hussein,” Kay said. “Transformation is possible now in a way that it was not possible for 35 years.”