The hard lessons of the Rwandan genocide discussed

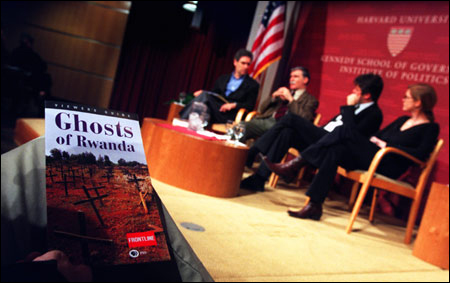

At Kennedy School, panel looks at Rwanda

International complicity and the lessons learned 10 years after the Rwandan genocide, in which almost a million people were slaughtered in eight weeks, was the topic of a compelling session at the Kennedy School’s John F. Kennedy Jr. Forum Tuesday night (March 23).

“How come I failed? How come my mission failed?… I lost soldiers and 800,000 people died,” said the force commander of the United Nations Mission for Rwanda in a clip from an upcoming PBS “Frontline” documentary, “Ghosts of Rwanda.”

The film features Lt. Gen. Romeo Dallaire, who joined moderator Michael Ignatieff, director of the Carr Center for Human Rights Policy, along with Pulitzer Prize-winning author Samantha Power, and Greg Barker, the film’s producer, in the discussion.

In another clip, Dallaire describes his desperate attempt to negotiate a ceasefire between Tutsi rebels and the Hutu government, after the U.N. refused to send any more troops. He met with rebel leaders at a Kigali hotel, where, upon greeting them he noticed blood spots on their hands. “I was not talking with humans. I literally was talking to evil,” he said. “It became an ethical problem. Do I negotiate with the devil … or do I shoot the bastards right there. I haven’t answered that question.”

Others in the film noted that the international community knew what was happening but did little to intervene. Samantha Power, whose book “A Problem From Hell” delves into the nature of the denial, noted that “the United Nations had an institutional interest to save ‘humanitarianism’ … [to save] the U.N. and to save peacekeeping. Somehow while 800,000 people were dying … saving the U.N. became associated with pulling peacekeepers out [of Rwanda].”

Dallaire questioned the motives of U.N. member countries. “After Mogadishu [Somalia], many countries were gun-shy,” he said. There were no strategic resources in Rwanda, he continued. “If you don’t have humanity as a backdrop, you revert to self-interest. Rwanda didn’t count because there was nothing there except humans.” Dallaire also noted that never once did any country introduce the idea of expanding his mandate in Rwanda. In contrast, “in Yugoslavia there were some 150 to 200 Security Council resolutions through that whole campaign.”

Power also described the lack of policy priority in Washington. “[President] Clinton never had a Cabinet meeting during the time.” She added that the only heated policy fight was between U.S. ambassador to the U.N., Madeleine Albright, and the White House. Albright insisted that at least 450 peacekeeping troops should stay so Dallaire could to try to maintain a ceasefire. Rwanda wasn’t in “America’s national interest,” said Power.

Of lessons learned, the panel noted that policy-makers need to think about the nature of denial, as well as personal, moral, and ethical responsibility that may involve breaking chain of command. Ultimately, Power said, some countries have to decide who is going to “own” the issue of genocide prevention. Everyone waits for the United States, and “there needs to be a division of labor on the international stage,” she said.

Dallaire noted that the term “genocide” is no longer taboo. There is a higher sensitivity to scenarios where it might happen again, he said. But of his experience there, of the Rwandan “eyes” that haunt him and images of piled corpses, Dallaire said he can never forget. “Rwanda will never be exorcised from me.”