Looking at Germany, Japan, Iraq: A tale of three occupations

U.S. ‘occupations’ compared by panel

Soon after the Bush administration revealed its plan to overthrow Saddam Hussein and bring democracy to Iraq, commentators began comparing this initiative with America’s occupation of Germany and Japan following World War II. Depending on one’s perspective, these comparisons could be positive (We’ve done it before and we can do it again) or negative (The situation in 1945 was entirely different; you don’t know what you’re getting into).

For someone with even the slightest hope that the lessons of history might shed light on current events, such a comparison would seem extraordinarily valuable, provided it could be made with expert knowledge and scholarly objectivity.

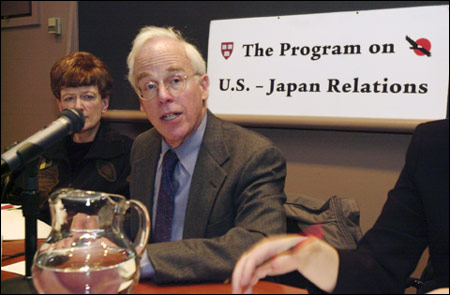

On March 3, a panel of scholars gathered at the Minda de Gunzburg Center for European Studies (CES) for just that purpose. Sponsored by the Program on U.S.-Japan Relations, the panel included John Dower, the Elting E. Morison Professor of History at the Massachusetts Institute of Technology, author of the Pulitzer Prize-winning book “Embracing Defeat: Japan in the Wake of World War II”; Charles Maier, the Leverett Saltonstall Professor of History, author of numerous books and articles on 20th century European history; and Eva Bellin, associate professor of political science at Hunter College, who has written extensively on the politics of the Middle East.

Susan Pharr, the Edwin O. Reischauer Professor of Japanese Politics and director of the the Program on US-Japan Relations, organized the event and served as moderator.

The discussion took place the day after explosions in Baghdad and Karbala killed more than 100 people on the Shiite holiday of Ashura, an event all three panelists remarked on.

“In Iraq almost every day seems to be a day of grief and mourning,” Dower said. “If you compare the situation with Japan, the contrast is stunning. For eight or nine years after the war, the Japanese were grieving and mourning, but not about what was taking place in front of them.”

During the occupation of Japan, incidents of violence were virtually unknown, Dower said. The source of grief for the Japanese was the death and destruction caused by nearly 15 years of war, whose termination, even if it meant defeat, they were eager to embrace.

“The hardship was extraordinary, as great or greater than Iraq,” Dower said.

During the war, 54 Japanese cities had been bombed and Tokyo had been reduced nearly to rubble. Three million Japanese had been killed and thousands more died later of malnutrition. Until 1949 the economy was plagued by hyperinflation, and only the black market showed any sign of vitality. And yet during this terrible time, the society remained relatively stable and secure, so much so that by 1950 the United States was able to reduce its occupying force from 450,000 to 150,000.

According to Dower, the intensity and duration of suffering in Japan was an important reason the occupation went so well.

“The Japanese said, ‘We were liberated from death.’ They were seizing the opportunity to start over, to create a new society.”

There were other factors as well. One was the occupation’s legitimacy. There had been a formal surrender by the Japanese and the occupation and reconstruction had been endorsed by Emperor Hirohito. Except for the military, the Japanese government remained intact at all levels, and the Japanese had a tradition of democracy and civil society on which to draw. There were no hostile political or religious factions within the country, and the fact that Japan was an island meant that there was little fear of terrorists or foreign fighters coming across the borders.

In addition, serious planning for the occupation had begun as early as 1942, and in the absence of television, the Internet, e-mail, and other forms of electronic communication, American authorities were able to maintain strict control over the sources of information in a way that is not possible today.

The occupation of Germany followed a very similar pattern, as Maier explained. Allied planning for the reconstruction of Germany had been going on since 1942; the Germans, like the Japanese, were weary of war and welcomed the chance to build a new society; and the German civil bureaucracy remained largely intact with a tradition of liberal, democratic government on which to build. As in Japan, there was no armed resistance, no assassinations or reprisals against collaborators, and no centers of terrorism in neighboring states.

One difference was that Germany became divided into eastern and western zones, but even this helped to ensure the success of the reconstruction, since West Germany had no choice but to cooperate with the Allies in order to gain protection against the Soviets.

Bellin generally agreed with her colleagues’ comparison of the occupation of Iraq and those of Germany and Japan. One important difference is the extent to which Iraq’s governmental and civil institutions have been destroyed.

“Japan and Germany were akin to a firm whose building has burned down and that needed an infusion of capital to get started again. Iraq is like a firm that is putting a business together for the first time, and, as we know, 70 percent of all new businesses fail.”

Specific factors working against the success of Iraq’s reconstruction, according to Bellin, are its religious and ethnic cleavages, which Saddam took every opportunity to deepen; its lack of effective, meritoriously organized bureaucratic systems; and the absence of any recent tradition of democratic government.

Ironically, the swiftness with which the United States toppled Saddam’s regime and the avoidance of civilian casualties may actually work against the success of the reconstruction, Bellin said. In Germany and Japan the experience of total defeat and devastation broke down old conventions and opened the people to new ideas. The much shorter war in Iraq with relatively little loss of life on the part of the civilian population did not produce this psychological impact, while the sanctions imposed on Iraq after its invasion of Kuwait in 1990 have probably increased resistance.

“The hardships under the sanctions were like a slow bleed rather than a sudden mortal shock, and a slow bleed often makes people more able to cope.”

Bellin’s prognostications were not all negative, however. She pointed out that Iraq, with its huge oil reserves, may be economically better off than Japan and Germany, which did not take off economically until the late 1940s or early 1950s. And while Iraq does not have any national figures with the prestige of the Japanese emperor to authorize reconstruction efforts, it is possible that someone like the Shiite leader Ali Sistani may emerge as a unifying force.

In the end, it may be the unpredictability of events that offers the greatest hope for a positive outcome in Iraq. Maier made this point with reference to the 1989 collapse of the Soviet Union.

“If you don’t allow for surprise, you’re not doing your job as a historian. 1989 was thrilling because so many historians like me said it would never happen.”