HLS students hear case before high court does

Supreme (moot) Court comes to Law School to argue privacy case

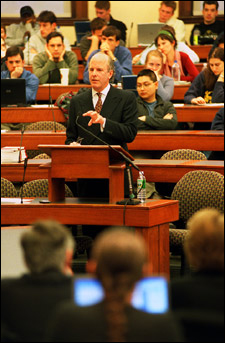

Harvard Law School, long a training ground for many of the nation’s sharpest legal minds, last week (March 9) coached some seasoned lawyers preparing a case

that’s on its way to the U.S. Supreme Court later this month. For the members of the legal defense team arguing the case, the moot court provided a realistic and informative platform for honing their arguments.

And the Harvard Law School (HLS) students who filled Austin North got an unprecedented opportunity to witness a real oral argument “as opposed to the two-minute version they might see on ‘Law and Order,’” said HLS lecturer Shaun Spencer. Spencer, a Climenko/Thayer Lecturer on Law, organized the event with Richard Sobel, senior research associate in the Program in Psychiatry and the Law at Harvard Medical School and author of an article on identity and privacy in the Harvard Journal of Law and Technology, which sponsored the event.

The case of Larry D. Hiibel v. The Sixth Judicial District Court of the State of Nevada concerns timely issues of individual privacy and the protection of the public. “It’s a very serious point of law that’s before this court,” said the Hon. Thayer Fremont-Smith HLS ’60, a retired Massachusetts Superior Court justice who served as chief justice for the moot court.

In May 2000, a Humboldt County, Nevada, sheriff’s deputy responded to a concerned bystander’s phone call reporting that a man — Hiibel — had struck a female inside a truck that was parked at the side of the road. After Hiibel refused – 11 times – to provide identification to the officer, he was arrested. Convicted of resisting a public officer, Hiibel appealed his case unsuccessfully before the Nevada District Court and Nevada Supreme Court. His appeal to the U.S. Supreme Court was successful, and on March 22, his defense team will argue that the Nevada law by which Hiibel was convicted is unconstitutional under the Fourth Amendment.

‘Hi, my name is private’

“Let me see some ID,” the deputy demanded repeatedly in a video of the arrest shown at the opening of the arguments.

“Why?” said Hiibel, a rangy middle-aged man in a cowboy hat.

“Because,” said the exasperated deputy.

“Why?”

“You’re facing arrest here if I don’t get some identification.”

The arrest video elicited snickers from the audience, as Hiibel and the deputy squared off with escalating stubbornness. Yet when Nevada Public Defender Robert Dolan, who will argue for Hiibel before the Supreme Court, began his argument, gravity descended upon the room.

The statute under which Hiibel was arrested is unconstitutional, Dolan argued, because it required Hiibel to identify himself, which violates the Fourth (unreasonable search and seizure) and Fifth (self-incrimination) Amendments.

“Our fundamental objection is that the statute … is a violation because it subjects a person to six months in jail for simply remaining silent,” Dolan

Learn more about the case and the upcoming Supreme Court oral arguments at http://www.epic.org/privacy/hiibel/.

said. “What’s before the court today is the value that we place in privacy … the right to be let alone, free from arbitrary interference by law enforcement.”

Yet obtaining identification is essential to good police work, countered Dolan’s colleague Harriet Cummings, swapping sides to portray the state of Nevada’s interests. It not only protects law enforcement officials, its infringement on civil liberties is limited.

As Dolan, then Cummings and James Logan, who argued for the United States, made their oral arguments, they were grilled with equal vigor by Fremont-Smith and five other “Supreme Court justices” from HLS and beyond.

Wouldn’t knowing the person’s name add to the arresting officer’s safety by giving him the opportunity to run a background check on his or her past criminal record? “Justice” Michael Meltsner, visiting professor at HLS, asked Dolan. If the person being arrested had a significant criminal record, Dolan answered, he or she would most likely provide a false name.

Lawrence Friedman, visiting professor of law at Boston College Law School, and several other justices quizzed Dolan on expectations of privacy. After all, we give out our names every day. And further, asked HLS Assistant Professor Samuel Bagenstos, how is giving one’s name more intrusive than a pat-down search?

A pat-down search is over quickly, Dolan replied, whereas giving one’s name allows officials to continue to search that person’s records.

Implications for homeland security

In her oral argument, Cummings maintained that one’s name is neither testimonial nor incriminating and thus demanding it does not violate the Fifth Amendment. “The name itself is inherently neutral,” she said. “Asking for one’s name is not likely to produce an incriminating answer.”

Arguing for the United States, Logan, also a defender in the state of Nevada Public Defender’s Office, continued Cummings’ argument that because we float our names through the public domain on a daily basis, it’s unreasonable to expect privacy in one’s name.

But aren’t expectations regarding privacy and identity changing? asked Frederick Schauer, the Stanton Professor of the First Amendment at the Kennedy School of Government. “In an era of identity theft and the like, people are more reluctant to give their names now,” he said.

“You work for John Ashcroft, right? Does this have any implications for homeland security?” asked Meltsner.

For combating terrorism or carrying out police work, said Logan, identifying people is necessary for public safety.

Valuable lessons

When the arguments closed, the justices turned from antagonists to allies, providing the three public defenders with insiders’ perspectives on the leanings of the individual justices and tips on structuring their arguments, although they characterized the case as an uphill battle.

Still, the value of the moot court was not lost on the Nevada team. “They saw weaknesses in the arguments they had already prepared, and they probably heard some new arguments, or at least new twists on arguments, that they could use in the real argument later this month,” said Spencer. “And as they say, practice makes perfect.”

For the students in the audience, most of whom were first-years anticipating their first oral arguments before a three-justice court in April, the opportunity to witness a “real” case gave them an educational experience far outside the legal library.

“I learned a lot about strategy, about how to conduct yourself in front of the justices,” said Kate Dornbush 1L.

Dave Garbett 1L took away a simpler lesson: “You should be nice to the judges,” he said.