At the Divinity School, passionate talk of ‘The Passion of the Christ’

Gibson film panned by religious scholars

The Harvard Divinity School (HDS) faculty members and guests who gathered Thursday (March 18) to discuss the much-talked-about new film “The Passion of the Christ” dissented only in their choice of adjectives.

“Deeply sadistic,” said Robert Orsi, Warren Professor of the History of Religion

in America. “Disturbing,” he continued. “Militaristic.”

“Pornographic,” added Ellen Aitken, assistant professor of the New Testament, with biting contempt.

“Obscene” and “blasphemous,” panelist and writer James Carroll wrote in an op-ed in The Boston Globe Feb. 24.

“Overwhelmingly bad news,” said Harvey Cox, Hollis Professor of Divinity. “A celebration of apocalyptic violence.”

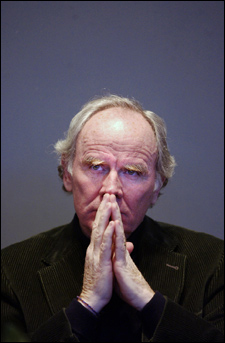

From the over-the-top violence of the film, directed by Mel Gibson, to its infidelity to the Gospels from which it draws its narrative to its portrayal of Jews, the panel – rounded out by Frothingham Professor of the History of Religion François Bovon and moderator Kevin Madigan, assistant professor of the history of Christianity – unanimously condemned “The Passion.” In the lively panel and discussion that followed, they presented reasons scholarly, political, spiritual, and visceral to loathe the film that has been a box office winner since its release.

Orsi reminded the audience of the film’s inspiration, in the passion plays that re-create Christ’s last days on Earth, performed by religious communities around the world. “I find myself thinking of Palm Sundays in the Bronx,” he said, recalling his own Italian-Catholic heritage. Yet unlike his own experience with passion plays, which involved the church congregation by having them shout, “Crucify him!”, this film distances its viewers from any sense of responsibility.

Orsi also expressed concern that the film connected violence and power in Christianity in a way that is especially disturbing in an era of increasing aggression in the name of religion, Christian and other. “I’m worried about how this movie is going to play around the world,” he said. “What does it say about American culture? What does it say about Christianity?”

HDS Panel on Mel Gibson’s The Passion of the Christ

Professor Kevin Madigan moderates a discussion on the recently released film. The panel also includes HDS professors Ellen Aitken, François Bovon, Harvey Cox, and Robert Orsi, as well as columnist and author James Carroll. The event took place in the Sperry Room of Andover Hall on March 18, 2004.

Us vs. them, then and now

Musing on the “shockingly positive reaction” the film has elicited from a broad audience, Carroll, a prize-winning writer and Roman Catholic, linked “The Passion of the Christ” to the current political scene. He read from the epilogue of his forthcoming book “Crusade: The Chronicles of an Unjust War,” a reckoning of the past several years’ war on terrorism and in Iraq, suggesting that the film’s appeal derives in part from its dramatization of George W. Bush’s “us versus them” spirit and its simplification of the complexity of good and evil.

Carroll voiced further concern about the film’s playing out of Gibson’s own theological convictions. The son of a man who denies the Holocaust, Gibson himself is, said Carroll, a “Holocaust minimizer” and a Catholic who rejects the reforms of Vatican II, which called for an end to blaming Jews for the death of Christ.

“Gibson’s bloody film celebrates the violence of the Crusades, then and now, making it a big-screen icon version of George W. Bush’s war,” said Carroll. “Its celebration of contempt for Jews is not incidental here, since for every victim, there has to be a victimizer, and Jews have long played that role in the Western imagination.”

Cox, who is teaching a course on fundamentalism this semester, rescinded his requirement that his students view the film after he saw it. “In fact, I would advise that you not see it,” he told them in an e-mail.

“This is more a reflection of the signs of our times than it is a reflection of biblical times,” he said. “It’s a celebration of apocalyptic violence in the interest of purification.” In the era of “shock and awe” and weapons of mass destruction, he said, “the idea of purification by apocalyptic violence is terribly dangerous.”

The Gospels according to Gibson

Several panelists slung scholarly barbs at “The Passion of the Christ,” including Aitkin, who noted that its biblical and historical missteps augmented some of the film’s most objectionable aspects. The film’s interpretation of the Bible’s passion narratives ignore the Old Testament Scripture quotations that run through the Gospels, she said.

The result of this, she said, is a breakdown of the connection between the passion narratives and the heritage of Israel. “It is another way of erasing Israel from the story,” she said.

She also noted the anachronistic absence of the Greek language in the film, which features only Latin and the ancient Semitic language of Aramaic. In reality, she said, Greek and other languages, such as dialects of Egyptian, would have been spoken. “It not only makes the movie completely historically false, but it also creates an ethnic polarity between the civilized people, who speak Latin … and these others,” she said, enhancing the “us versus them” political slant Carroll noted.

Although Gibson claimed “The Passion of the Christ” remains true to the history of the Gospels, Bovon pointed out that this might be a hollow claim. “The Gospels are history and interpretation,” he said. “The Gospels are not our best sources to the history of the passion of Jesus.”

“The problem is that much of this stuff in the movie is in the Gospels,” countered Cox. “It’s read every Good Friday in churches.” The film may push Christians, he said, to scrutinize what he called “these terrible passages” of canonical sources.

The panel filled the Sperry Room of HDS’s Andover Hall beyond capacity, and the panelists’ remarks sparked lively questions and comments from the audience members. Such discussion and reflection may be, said Cox, the film’s most positive legacy.

“This is an opportunity for re-education,” he said, admitting he was grasping for a silver lining in the dark storm cloud of “The Passion of the Christ.” “I hope it isn’t lost.”