Academic turns city into a social experiment

Mayor Mockus of Bogotá and his spectacularly applied theory

Antanas Mockus had just resigned from the top job of Colombian National University. A mathematician and philosopher, Mockus looked around for another big challenge and found it: to be in charge of, as he describes it, “a 6.5 million person classroom.”

Mockus, who had no political experience, ran for mayor of Bogotá; he was successful mainly because people in Colombia’s capital city saw him as an honest guy. With an educator’s inventiveness, Mockus turned Bogotá into a social experiment just as the city was choked with violence, lawless traffic, corruption, and gangs of street children who mugged and stole. It was a city perceived by some to be on the verge of chaos.

People were desperate for a change, for a moral leader of some sort. The eccentric Mockus, who communicates through symbols, humor, and metaphors, filled the role. When many hated the disordered and disorderly city of Bogotá, he wore a Superman costume and acted as a superhero called “Supercitizen.” People laughed at Mockus’ antics, but the laughter began to break the ice of their extreme skepticism.

Mockus, who finished his second term as mayor this past January, recently came to Harvard for two weeks as a visiting fellow at the Kennedy School’s Institute of Politics to share lessons about civic engagement with students and faculty.

“We found Mayor Mockus’ presentation intensely interesting,” said Adams Professor Jane Mansbidge of the Kennedy School, who invited Mockus to speak in her “Democracy From Theory to Practice” class. “Our reading had focused on the standard material incentive-based systems for reducing corruption. He focused on changing hearts and minds – not through preaching but through artistically creative strategies that employed the power of individual and community disapproval. He also spoke openly, with a lovely partial self-mockery, of his own failings, not suggesting that he was more moral than anyone else. His presentation made it clear that the most effective campaigns combine material incentives with normative change and participatory stakeholding. He is a most engaging, almost pixieish math professor, not a stuffy ‘mayor’ at all. The students were enchanted, as was I.”

A theatrical teacher

The slim, bearded, 51-year-old former mayor explained himself thus: “What really moves me to do things that other people consider original is my passion to teach.” He has long been known for theatrical displays to gain people’s attention and, then, to make them think.

Mockus, the only son of a Lithuanian artist, burst onto the Colombian political scene in 1993 when, faced with a rowdy auditorium of the school of arts’ students, he dropped his pants and mooned them to gain quiet. The gesture, he said at the time, should be understood “as a part of the resources which an artist can use.” He resigned as rector, the top job of Colombian National University, and soon decided to run for mayor.

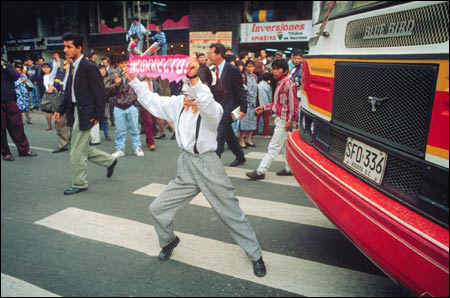

The fact that he was seen as an unusual leader gave the new mayor the opportunity to try extraordinary things, such as hiring 420 mimes to control traffic in Bogotá’s chaotic and dangerous streets. He launched a “Night for Women” and asked the city’s men to stay home in the evening and care for the children; 700,000 women went out on the first of three nights that Mockus dedicated to them.

When there was a water shortage, Mockus appeared on TV programs taking a shower and turning off the water as he soaped, asking his fellow citizens to do the same. In just two months people were using 14 percent less water, a savings that increased when people realized how much money they were also saving because of economic incentives approved by Mockus; water use is now 40 percent less than before the shortage.

“The distribution of knowledge is the key contemporary task,” Mockus said. “Knowledge empowers people. If people know the rules, and are sensitized by art, humor, and creativity, they are much more likely to accept change.”

Mockus taught vivid lessons with these tools. One time, he asked citizens to put their power to use with 350,000 “thumbs-up” and “thumbs-down” cards that his office distributed to the populace. The cards were meant to approve or disapprove of other citizens’ behavior; it was a device that many people actively – and peacefully – used in the streets.

He also asked people to pay 10 percent extra in voluntary taxes. To the surprise of many, 63,000 people voluntarily paid the extra taxes. A dramatic indicator of the shift in the attitude of “Bogotanos” during Mockus’ tenure is that, in 2002, the city collected more than three times the revenues it had garnered in 1990.

Another Mockus inspiration was to ask people to call his office if they found a kind and honest taxi driver; 150 people called and the mayor organized a meeting with all those good taxi drivers, who advised him about how to improve the behavior of mean taxi drivers. The good taxi drivers were named “Knights of the Zebra,” a club supported by the mayor’s office.

Yet Mockus doesn’t like to be called a leader. “There is a tendency to be dependent on individual leaders,” he said. “To me, it is important to develop collective leadership. I don’t like to get credit for all that we achieved. Millions of people contributed to the results that we achieved … I like more egalitarian relationships. I especially like to orient people to learn.”

Taking a moral stand

Still, there were times when Mockus felt he needed to impose his will, such as when he launched the “Carrot Law,” demanding that every bar and entertainment place close at 1 a.m. with the goal of diminishing drinking and violence.

Most important to Mockus was his campaign about the importance and sacredness of life. “In a society where human life has lost value,” he said, “there cannot be another priority than re-establishing respect for life as the main right and duty of citizens.” Mockus sees the reduction of homicides from 80 per 100,000 inhabitants in 1993 to 22 per 100,000 inhabitants in 2003 as a major achievement, noting also that traffic fatalities dropped by more than half in the same time period, from an average of 1,300 per year to about 600. Contributing to this success was the mayor’s inspired decision to paint stars on the spots where pedestrians (1,500 of them) had been killed in traffic accidents.

“Saving a single life justifies the effort,” Mockus said.

The former mayor had to address many fronts simultaneously. In his struggle against corruption, he closed down the transit police because many of those 2,000 members were notoriously bribable.

Mockus was a constant presence in the media, promoting his civic campaigns. “My messages about the importance of protecting children from being burned with fireworks, protecting children from domestic violence, and the sacredness of life reached many, including the children,” he said.

Once the mother of a 3-year-old girl called his office to say that meeting Mockus was her daughter’s only birthday wish.

But the meeting also revealed, said Mockus, that Colombian society has a long way to go. During the visit, the mother told him: “When I am going to hit her, she runs to the telephone and says that she is going to call Mockus. She doesn’t even know how to dial a number, but obviously she thinks that you would protect her.” Mockus, who has two daughters himself, was shocked at the woman’s nonchalance about striking her daughter.

Women’s night and mimes

There is almost always a civics lesson behind Mockus’ antics. Florence Thomas, a feminist and a professor at Colombian National University, pointed out to Mockus that in Bogotá women were afraid to go out at night. “At that time, we were also looking for what would be the best image of a safe city, and I realized that if you see streets with many women you feel safer,” Mockus explained.

So he asked men to stay home and suggested that both sexes should take advantage of the “Night for Women” to reflect on women’s role in society. About 700,000

More of Mockus in Bogotá

Here are a few more innovations from Antanas Mockus’ two mayoral terms:

- Mockus mobilized people to protest against violence and terrorist attacks. He invented a “vaccine against violence,” asking people to draw the faces of the people who had hurt them on balloons, which they then popped. About 50,000 people participated in this campaign.

- Mockus also embraced the concept of community policing. He tried to bring the community and the police closer together through the creation of Schools of Civic Security and local security fronts. In 2003, there were about 7,000 local security fronts in Bogotá. “It is very important to understand that the Schools and Fronts respond to a civic ideal. They have nothing to do with firearms but basically promote community organization,” Mockus points out.

- Voluntary disarmament days were held in December 1996 and again in 2003. Though less than 1 percent of the firearms in the city were given up, homicides fell by 26 percent, thanks in part to the attention given to the program by the media. The percentage of people who think that it is better to have firearms in order to protect themselves fell from 24.8 percent in 2001 to 10.4 percent in 2003.

- In 2003, the Mockus administration provided 1,235,000 homes with sewage service and 1,316,500 with water services. The city’s provision of drinking water rose from 78.7 percent of homes in 1993 to 100 percent in 2003. The sewage service rose from 70.8 percent of homes in 1993 to 94.9 percent in 2003.

- When Mockus assumed power, many city positions were distributed according to council members’ recommendations. “I stopped that, and some called me an anti-patronage fundamentalist,” Mockus said. He remembers that when he handed a text explaining his goals of transparency to one key council member, the council member first smiled, but later resigned.

women went out, flocking to free, open-air concerts. They flooded into bars that offered women-only drink specials and strolled down a central boulevard that had been converted into a pedestrian zone.

To avoid legal challenges, the mayor stated that the men’s curfew was strictly voluntary. Men who simply couldn’t bear to stay indoors during the six-hour restriction were asked to carry self-styled “safe conduct” passes. About 200,000 men went out that night, some of them angrily calling Mockus a “clown” in TV interviews.

But most men graciously embraced Mockus’ campaign. In the lower-middle-class neighborhood of San Cristobal, women marched through the streets to celebrate their night. When they saw a man staying at home, carrying a baby, or taking care of children, the women stopped and applauded.

That night the police commander was a woman, and 1,500 women police were in charge of Bogotá’s security.

Another innovative idea was to use mimes to improve both traffic and citizens’ behavior. Initially 20 professional mimes shadowed pedestrians who didn’t follow crossing rules: A pedestrian running across the road would be tracked by a mime who mocked his every move. Mimes also poked fun at reckless drivers. The program was so popular that another 400 people were trained as mimes.

“It was a pacifist counterweight,” Mockus said. “With neither words nor weapons, the mimes were doubly unarmed. My goal was to show the importance of cultural regulations.”

A bigger classroom?

Mockus noted that his administrations were enlightened by academic concepts, including the work of Nobel Prize-winning economist Douglass North, who has investigated the tension between formal and informal rules and how economic development is restrained when those rules clash; and Jürgen Habermas’ work on how dialogue creates social capital. Mockus also mentions Socrates, who said that if people understood well, they probably would not act in the wrong way.

Luis Eduardo Garzón, the new mayor of Bogotá, is the first leftist who has been in charge of the second-most important political position in Colombia. Said Mockus, “His election expresses a consensus around the importance of addressing social issues. Garzón has the challenge of opening space to new political forces in a country that has been dominated by a ‘bipartidismo bobo’ (dumb two-party system).”

Mockus – a sterling exemplar of the current vogue in Latin America for “anti-politicians” – says that transforming Bogotá’s people and their sense of civic culture was the key to solving many of the city’s problems. He is looking forward to returning to the classroom at Colombian National University after a sabbatical year. But Mockus is also considering the possibility of launching a presidential campaign – and perhaps being in charge of a 42 million student classroom.

María Cristina Caballero, a native of Bogotá, is a fellow at Harvard University’s Center for Public Leadership at the John F. Kennedy School of Government.