Up from slavery

Jean Fagan Yellin tells heroic story of former slave Harriet Jacobs

In her autobiography “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl: Written by Herself,” former slave Harriet Jacobs left an extraordinary legacy. The 1861 book chronicles Jacobs’ life in slavery, her master’s persistent unwanted sexual advances, the seven years she spent hiding in a crawl space above her grandmother’s porch, and her eventual flight to the North.

But because “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl” ends with Jacobs’ escape, the landmark work leaves untouched Jacobs’ formidable post-slavery career: as an abolitionist, an activist, a feminist, and an author.

Jean Fagan Yellin, renowned scholar of African-American women’s writings and the editor of a 1987 edition of Jacobs’ “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl,” has filled in Jacobs’ portrait with the new book “Harriet Jacobs: A Life” (Basic Civitas Books, 2004), which draws on original sources and extensive research to tell Jacobs’ story before, during, and after slavery.

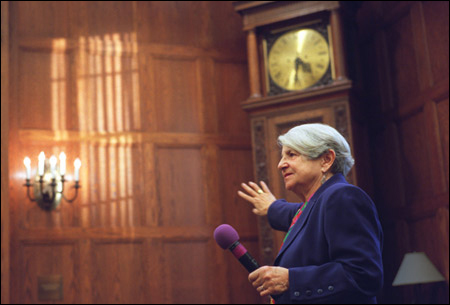

“Her life in freedom was as extraordinary as her life had been in slavery and as a fugitive,” Yellin told an audience at the Barker Center on Feb. 10, where she spoke as a guest of the W.E.B. Du Bois Institute.

Yellin described Jacobs, whose “Incidents” was originally published in 1861, as “a literary phenomenon and a historical phenomenon.” “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl” has been translated into many languages, and Jacobs’ is one of the most-visited graves in Cambridge’s Mt. Auburn Cemetery.

Slavery, hiding, bittersweet freedom

The public’s interest in Jacobs mirrors Yellin’s own. “It’s such a compelling story,” she said. “This is a long and productive and historic life. Who wouldn’t be interested?”

Harriet Jacobs was born a slave in Edenton, N.C., in 1813, “but I never knew it until six years of happy childhood passed away,” she wrote under the pen name of Linda Brent. “Though we were all slaves, I was so fondly shielded that I never dreamed that I was a piece of merchandise.”

While her early years were spent with a benevolent mistress, she soon became the slave of Dr. James Norcum, who sexually harassed her. When Norcum forced Jacobs to choose between a life of hard plantation work or living as his concubine, she fled to the nearby house of her free grandmother, where she hid in a crawl space – Yellin described it as just slightly larger than a library table – for nearly seven years.

With Norcum in pursuit, Jacobs fled north in 1842, where she worked for the Willis family in New York City, then moved to Rochester, N.Y., immersing herself in the feminist and abolitionist movements thriving in that city. Working in an anti-slavery reading room above the offices of Frederick Douglass’ North Star newspaper, she met Amy Post, with whom she lived and who convinced Jacobs to tell her story.

Jacobs returned to work for the Willises (three of whose descendents attended Yellin’s talk) in New York. In 1852, Cornelia Willis bought Jacobs’ freedom, which Jacobs’ viewed as a bittersweet victory.

“Knowing that the Norcums could no longer seize her and her children didn’t prevent her from feeling anguished at the means by which her freedom had been won,” Yellin read from “Harriet Jacobs: A Life.” Jacobs wrote to Amy Post, “The freedom I had before the money was paid was dearer to me. God gave me that freedom.”

It was Post who suggested, perhaps to alleviate what she perceived to be Jacobs’ depression, that Jacobs write an account of her life to contribute to the anti-slavery movement. Hesitant at first, Jacobs wrote, “If it would help save another from my fate, it would be selfish and un-Christian of me to keep it back.”

Writer as detective

Yellin, who began work on her “Harriet Jacobs: A Life” while a fellow at the Du Bois Institute 10 years ago, described the cross-country sleuthing that led to her 1987 edition of “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl.” Yellin followed a flimsy paper trail from Rochester, N.Y., to Smith College, which held a valuable letter from Jacobs, to Edenton. At the North Carolina State Archives in Raleigh, an archivist turned out to be a hard-working ally.

Because “Incidents” was published anonymously, many believed that the book’s editor, Medford-born abolitionist and writer Lydia Maria Child, was in fact its author. Yellin’s detective work sought to determine that the book was written by Jacobs, and that it was an autobiography, not a novel.

Her painstaking research verified both points, and, as the graduate students in the audience testified, Jacobs’ book and Yellin’s scholarly work on it has been a valuable source to future scholars. When Yellin published her edition of “Incidents” in 1987, however, “I really thought I was done with Harriet Jacobs,” she said. But Jacobs’ letters and papers from her life and work in freedom drew the scholar back in.

During and after the Civil War, Yellin said, Jacobs used the fame that “Incidents in the Life of a Slave Girl” gained her to raise money for relief missions in the South. She traveled to Alexandria, Va., where slaves had fled behind Union lines, and brought money, food, clothing, and medical care.

Yellin chronicled Jacobs’ life in Cambridge, where from 1869 to 1873 she ran an elegant boarding house for Harvard faculty on Mt. Auburn Street. There, she circulated among a wide and varied social group that included many privileged whites who knew of her through the celebrity of “Incidents.” Harvard mathematician Chauncy White was a boarder, and his friend Henry James was a frequent visitor.

In 1877, Jacobs moved to Washington, D.C., where she eventually died in 1897. Yellin described what she called “an astonishing event” that occurred in Washington in 1885. Jacobs had learned that the widow and children of Norcum, her former master and tormentor, were living in Washington and in poverty. Despite the injustices she and her family felt under the Norcums’ ownership, Jacobs brought groceries to Norcum’s young widow.

Reading from “Harriet Jacobs: A Life,” Yellin presented a nuanced view of what Jacobs might have felt in this act of charity. “As she gave to the family of her dead enemy, did she feel that finally she was achieving victory?” she wrote.