Scientists identify antibody that blocks SARS virus infection

Potential candidate for early treatment

An antibody plucked from a “library” of human antibodies has powerfully blocked infection by the SARS (severe acute respiratory syndrome) virus in laboratory tests, scientists at Harvard-affiliated Dana-Farber Cancer Institute report. This discovery could expedite the development of an antibody drug for the prevention or early treatment of SARS, which killed nearly 800 people in a global outbreak last year.

Researchers from Dana-Farber, Brigham and Women’s Hospital, the U.S. Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC), and Children’s Hospital Boston discovered that the antibody neutralized SARS infection in a laboratory setting by blocking the virus from entering cultured cells. The experiments are continuing in animal models of SARS, and the researchers are discussing future trials in humans. The findings will be posted on the PNAS Online Early Edition of the Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences.

Wayne Marasco of Dana-Farber and colleagues isolated the monoclonal antibody and demonstrated its effectiveness within six months after the SARS virus was discovered. “This is really a proof of principle for responding to emerging infectious diseases,” says Marasco, the paper’s senior author. “If the international community works together, it can make a serious dent in the time it takes to develop protective treatments against these threats.”

The paper’s first author is Jianhua Sui, a research fellow at Dana-Farber.

SARS, a highly contagious illness that often progresses to pneumonia and is sometimes fatal, was first reported in Asia in February 2003. Over the next several months it spread to more than two dozen countries in North America, South America, Europe, and Asia, and infected nearly 8,100 people (only a few in the United States) before it was contained. Early this year, Chinese authorities confirmed three new cases in that country, but there has been no sign of a renewed outbreak.

Even without a current crisis, scientists say the SARS threat has not been eradicated, and they are working urgently to develop a preventive vaccine and effective treatment for the disease, neither of which exist.

An antibody is a special blood protein that defends against bacteria, viruses, and other foreign substances that enter the body. Evolution has equipped the immune system to generate specific antibodies to fight almost any foreseeable invader, through a mechanism that uses genetic material from immune cells in a powerful combinatorial way that can produce billions of antibodies.

The SARS virus-specific human monoclonal antibody isolated by Marasco’s team in Dana-Farber’s Center for Cancer Immunology and AIDS was selected from Marasco’s collection, one of the world’s largest human antibody phage display libraries. The collection contains about 27 billion monoclonal antibodies generated by a mixture of blood cells from 57 human donors.

Last spring, scientists published the genetic sequence of the SARS virus, which is a type of coronavirus. Shortly afterward, Sui and her colleagues started to identify antibodies against a synthetic S1 protein that was made in the lab of Michael Farzan of the Partners AIDS Research Center at Brigham and Women’s.

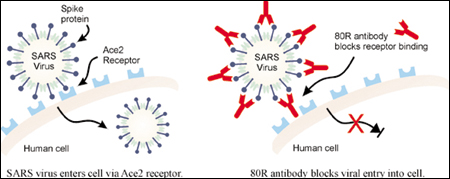

The S1 protein is a building block of the virus’ “spike” structure that enables it to infect host cells. The researchers coated test tubes with the S1 protein, and poured in a solution containing the antibody libraries. From this vast collection, they selected eight antibodies that recognized and bound to the S1 protein, and thus might be able to interfere with the virus’ infection mechanism. The eight antibodies were tested in the CDC laboratories in Atlanta, where scientists found that one of the antibodies (labeled the 80R antibody) potently blocked live SARS viruses from entering cultured human cells. “It was one of those ‘Eureka!’ experiences,” says Marasco. “It was pretty dramatic.”

Marasco says the 80R antibody is an effective viral entry inhibitor that looks promising in animal tests and could be commercially developed for testing in clinical trials. “It would be very satisfying to see this go into humans and do good,” says Marasco, who is also an associate professor of medicine at Harvard Medical School. He believes the antibody could be widely available before a successful conventional vaccine is developed, and he would like to see it tested in the southern province of mainland Southern China and Hong Kong in collaboration with scientists from these regions.