Rights activists pass the torch

At HMS, Bond, faculty describe experiences to high schoolers

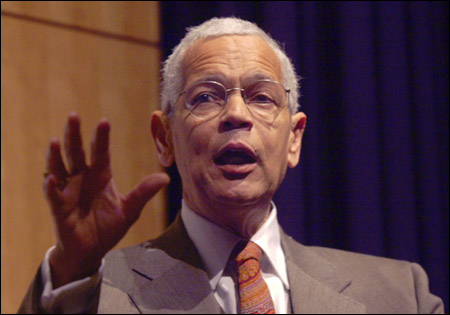

Julian Bond, chairman of the National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP), joined Harvard Medical School (HMS) faculty members last Wednesday (Feb. 4) to share memories of the civil rights era with Boston youth, describing the time’s difficult work and telling the children that future struggles for justice will be theirs.

“If you sit by and watch the world go by and see things you don’t like, you have nobody to blame for that but you,” Bond said during a 45-minute speech in Harvard Medical School’s New Research Building.

Bond was the keynote speaker for “Reflection in Action: Building Healthy Communities,” an all-day commemoration of Black History Month that partnered Harvard Medical School with Boston schools and community organizations. The event was dedicated to the Civil Rights Movement and to its effect on health disparities and social justice.

“That’s what this is about, the community coming to Harvard,” said Joan Y. Reede, HMS’s dean for diversity and community partnership.

Reede said the event was more successful than organizers expected, attracting about 260 teachers, students, and parents. The day kicked off with the presentation of awards to student winners of a contest for creative works about the Civil Rights Movement’s history.

Reede said she believed people turned out because they share a sense that memories of that time are fading and as they do, so do the hard-won lessons.

“They want to help youth understand they can make a difference,” Reede said. “People can make a change. People can make our community better, and the youth need to know it.”

The day included morning award presentations and performances by the students. The afternoon session included Bond’s keynote speech and panel discussions featuring Harvard Medical School faculty. The two panels addressed the topics of how far we’ve come and how far there is yet to go on the issue of civil rights and health care.

Harvard Medical School Dean Joseph Martin introduced Bond. Martin said that as a member of the Boston community, the School feels an obligation to work to improve its community by hosting events such as “Reflection in Action.”

“There are not enough individuals stepping forward saying community is important, saying social justice is important,” Martin said.

Speakers described segregation in the United States before the civil rights era. They spoke of whites-only hospitals that wouldn’t admit ailing or injured blacks. They spoke of adult black Southerners who, after meeting medical workers in the civil rights battle, received the first checkups of their lives.

They described abject poverty and hunger, segregated schools, theaters, and restaurants, and they spoke of the violence that awaited those fighting to end the system.

Bond aimed his talk at the children in the audience, telling of his own teen years when, as a 17-year-old living outside of Philadelphia, he and his friends were enamoured with the new television show “American Bandstand,” where Philadelphia teens danced to the latest popular music.

But the events in Little Rock, Ark., that year distracted his thoughts from dance and style. That was the year when nine black teenagers became the focal point of the civil rights struggle as the federal government ordered the desegregation of Little Rock’s Central High School.

Bond said he followed the struggle intently, wondering often if he would have had the courage to endure what they endured.

In 1960, he found out. While attending Morehouse College, Bond and other students inspired by the F.W. Woolworth lunch counter sit-in in Greensboro, N.C., led a group of protesters to the segregated cafeteria in the basement of the Atlanta City Hall. They were denied service and arrested after refusing to leave.

From there Bond was one of many students who helped organize the Student Nonviolent Coordinating Committee (SNCC), and he dropped out of college a month short of graduation to work with SNCC to support and organize sit-ins and other protests.

Bond and other speakers urged students to get involved. Leon Eisenberg, the Maude and Lillian Presley Professor of Social Medicine, Emeritus, said the struggle continues. Eisenberg described early struggles to increase the number of black and minority students at the Medical School. Work remains to be done, even close to home, Eisenberg said. Though HMS has made large strides in fostering a diverse student body, the faculty has too few minority members, especially at higher levels.

“Human rights exist only as long as people are willing to fight for them,” Eisenberg said.

Alvin Poussaint, professor of psychiatry and associate dean for student affairs, told of working with the Medical Committee for Human Rights, an organization of doctors and other health-care workers who tended the medical needs of protesters.

Poussaint spoke of the voting rights march from Selma to Montgomery, Ala., and of President Lyndon Johnson’s signing of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which ended state-sponsored disenfranchisement of black voters.

Poussaint said they had to use hearses provided by black-owned funeral homes because white-owned ambulance companies wouldn’t transport black patients.

“It was a success at the cost of many lives,” Poussaint said of the voting rights struggle. “It’s painful today that so many people don’t register to vote, when so many people sacrificed to get them their [voting] rights.”