Ozone standards may be too lax

Harvard researchers will present their findings to Congress

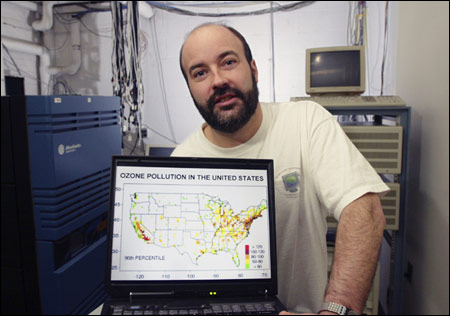

Harvard researchers are weighing in on the national ozone pollution debate, asserting that federal assumptions on natural background levels are wrong and may result in national standards that permit too much ozone pollution.

Arlene Fiore, a postdoctoral fellow at Princeton University who conducted the research while a doctoral student at Harvard, and Daniel Jacob, Gordon McKay Professor of Atmospheric Chemistry and Environmental Engineering, made their assertions in a recent article in the Journal of Geophysical Research.

“Our work suggests that the EPA is presently overestimating background concentrations,” Fiore said. “This overestimate of the background might lead to a greater health risk due to imposing weaker regulations on ozone.”

The two will share their conclusions with federal lawmakers next week at a Senate briefing in Washington, D.C. The testimony comes as the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency conducts a regular re-evaluation of its air pollution standards.

The journal article, co-authored with colleagues from Harvard, the National Institute of Aerospace, and NASA Langley, says that the EPA 40 parts per billion assumption of background ozone is too high. Their studies show that the actual natural background levels are probably around 20 parts per billion, ranging as high as 35 parts per billion.

The difference is a critical one, Jacob and Fiore said, because acceptable pollution levels are measured as an increment above the background level. Unlike some other pollutants, there are no safe levels of ozone – even small amounts can be harmful to one’s health.

Ozone pollution has been implicated in a variety of negative health effects, including shortness of breath, coughing, and respiratory irritation. While ground-level ozone is considered a pollutant, high in the atmosphere, ozone plays a beneficial role shielding the Earth from harmful ultraviolet rays.

The implication of their work is that the EPA is not being as strict as it could in regulating polluters. Fiore and Jacob said that is particularly true during the worst ozone pollution events, when environmental conditions favor low background ozone levels, giving the government even more room to crack down on polluters.

“In this case, the EPA might then decide that the health risks on polluted days warrant setting more stringent standards,” Fiore said. “The idea then is that tighter standards should result in lower ambient ozone concentrations, and cleaner air to breathe.”

Fiore and Jacob’s study contradicts recent industry-funded studies that indicate that background ozone is higher, not lower, than current EPA standards. If correct, those industry studies, which measure ozone in relatively untouched areas in the West, could be interpreted to mean that federal ozone pollution regulations are too strict, Jacob said.

The problem with those studies, Jacob said, is that when it comes to ozone, no area is pristine. Ozone pollution blows across the nation, raising levels even in areas that may appear unpolluted.

“The whole Northern Hemisphere is polluted with human-produced ozone, it’s not natural,” Jacob said.

Fiore and Jacob used a three-dimensional computer model of global atmospheric chemistry to simulate what would happen if all the man-made sources of ozone pollution were removed.

What they found was that actual background levels are quite variable and change depending on the season, altitude, and weather conditions. Even with that variability, however, the range of normal background ozone concentrations was less than the EPA’s 40 parts per billion.

“What we found was that natural background ozone is really more like 20 parts per billion rather than 40. It’s certainly no higher than 40,” Jacob said. “Certainly, [the standard] should not be relaxed further.”

Good up high, bad nearby

In some ways, ozone is like real estate: What’s important is location, location, location.

Ozone, a gas made up of oxygen, is beneficial when found high in the atmosphere. There, safely ensconced in the ozone layer, ozone forms a protective shield around the Earth, blocking potentially harmful ultraviolet rays. Ozone depletion and the formation of holes in the ozone layer have been great cause for concern in recent years and have led to the banning of certain uses for some ozone-killing chemicals.

Closer to the ground, however, ozone is considered a pollutant and can cause respiratory irritation, asthma attacks, and shortness of breath. It can also harm vegetation and is responsible for an estimated $500 million in crop losses each year, according to the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency (EPA).

Ozone pollution levels rise in summertime, particularly in urban areas, when the hot sun, stagnant air masses, and pollutants like those commonly found in automobile exhaust and industrial and power plant emissions combine to generate ozone and keep it in place.

For more information on the two faces of ozone, visit the EPA Web site “Good Up High, Bad Nearby”.