Menand brings pragmatists of the Metaphysical Club to life

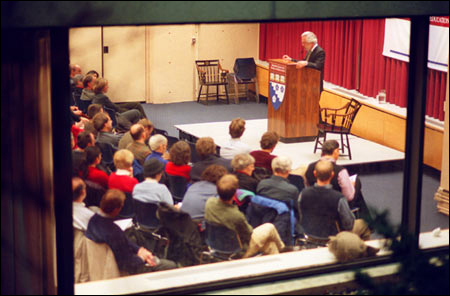

Cultural historian Louis Menand lectured Feb. 12 on the three moments when pragmatism, a quintessentially American philosophy that he defined as “an idea about ideas,” gained ascendancy in American intellectual life. Unfortunately, according to Menand, the third and last moment has just passed.

A distinguished scholar known for academic research as well as for essays and reviews in such publications as The New Yorker and the New York Review of Books, Menand is the author of “The Metaphysical Club: A Story of Ideas in America” (2001), a best seller that won both the Francis Parkman Prize from the Association of American Historians and the Pulitzer Prize for History. He joined the Harvard faculty in 2003 as Professor of English and American Literature and Language.

The Metaphysical Club of the book’s title flourished for only a few months in Cambridge in 1872. Its members included three young men who would later achieve intellectual prominence – the philosopher and psychologist William James, the future Supreme Court Justice Oliver Wendel Holmes Jr., and the brilliant polymath and father of semiotics Charles Sanders Peirce.

Peirce is said to have given the club its name. If so, perhaps he meant it ironically, for pragmatism, the philosophy to which it gave birth, is the very opposite of metaphysics.

“The pragmatists believed that ideas were tools,” said Menand, “that they were produced by groups and were dependent on human carriers and on the environment, like germs.”

Ideas, in this view, are simply mental constructs that humans forge in order to cope with the world. Ideas do not exist in some ideal realm waiting to be discovered, any more than did the telegraph or the cotton gin. They are brought into existence to deal with the environment, and when the environment changes, ideas change as well.

According to Menand, the two greatest influences on pragmatism were the Civil War and Darwin’s “Origin of Species.”

The Civil War, erupting out of a long and bitter national debate over slavery and resulting in staggering losses of life and property, convinced many of the younger generation to reject any and all absolutes.

“The Civil War discredited the assumptions of the generation before it. The postwar reaction was against certitude and philosophical infallibility. There was a sense that the country had been too sure of itself.”

Meanwhile, another sweeping change had been set in motion by the publication of Charles Darwin’s “Origin of Species” in 1859. By the time the Metaphysical Club began meeting in 1872, most scientists had accepted the book’s basic insight that evolution comes about through the natural selection of organisms that are better adapted to their environment.

“Pragmatism is Darwin’s theory of natural selection applied to philosophy. The pragmatists asked the question, why do we have minds? According to the Darwinian view, organisms with minds would be naturally selected over organisms without minds.”

Pragmatists determine truth not through an appeal to some outside process, but based on the results of accepting the idea as true. “Truth happens to an idea,” said James.

This view was contrary to the traditional assumption of philosophy that the mind’s goal is to accurately mirror reality. “There is no evolutionary logic to having a mirror in our heads,” Menand said. “Knowledge is always partial and provisional because it was for partial and provisional reasons that we sought it.”

Pragmatism was perfectly suited to the expansive, industrialized America that surged into being after the Civil War ended, “an America run by former Union generals who pushed the country into modernity…. Pragmatism is the name for America coming to terms with modernity. It is the modernist philosophy, par excellence.”

By modernity, Menand means a society in which life is no longer thought of as cyclical, in which people are the agents of their own destiny, and neither the individual’s nor the society’s future is predetermined.

“There is no greater gesture of honor in modern society than to be described as being ahead of one’s time, although it is one from which the honoree is unable to benefit,” Menand said.

Although pragmatism perfectly suited the emerging America of the post-Civil War era, it did not actually become a philosophical movement until 1898 when James first used the term in a lecture. This was the beginning of pragmatism’s second moment, which reached its apogee when a partnership developed between James and his intellectual heir, John Dewey. “They were the tag team of American philosophy until James died in 1910,” Menand said.

That moment ended with the start of the Cold War, when the country’s intellectual life again became dominated by ideologies. The Communist bloc and the capitalist West each defined itself in opposition to the other. There was little room for a philosophy like pragmatism that “wished to bring ideas and beliefs down to the human level because it wished to avoid the violence inherent in abstraction.” Instead, nearly all disciplines aspired to the objectivity and disinterestedness that was believed to characterize the hard sciences.

Pragmatism’s third moment began in the late 1980s and early 1990s after the fall of the Soviet Union and the end of the Cold War. A new generation of critics and theorists such as Richard Rorty, Stanley Fish, and Richard Posner introduced a neopragmatist perspective into the study of history, law, literature, and culture, a perspective that did not hesitate to treat even science as an endeavor whose claims to truth were contingent rather than absolute.

It may be too soon to tell, but Menand believes that the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11, 2001, may have marked the end of pragmatism’s third moment. “The world turned a page on 9/11,” he said. “That event marked an end of irony, postmodernism, skepticism. The world had become too serious, and vigilance required metaphysics.”

What Menand finds ironic is that many intellectuals (“who should have known better”) reacted to the fundamentalist certitude of the terrorists by becoming “liberal messianists,” turning the idea of intellectual freedom into a rigid absolute.

“I do suspect that pragmatism’s third moment is probably over,” Menand said.