History of the Japanese at Harvard

When Jewish and black students were excluded, Japanese students were accepted into final clubs and other exclusive societies

Many have compared the terrorist attacks of Sept. 11 with Japan’s surprise attack on Pearl Harbor, drawing parallels between their unexpectedness, their devastating impact on the national consciousness, their inauguration of a new political reality.

For Susan Pharr, the Edwin O. Reischauer Professor of Japanese Politics, the events of 9/11 brought up another comparison – between the position of Arab and Islamic students in the wake of 9/11 and that of Japanese students after Dec. 7, 1941.

“The day after 9/11, as people began gathering in Harvard Yard, I began wondering what it must have been like to have been a student from Japan after Pearl Harbor,” Pharr said.

The thought led her to begin delving through the Harvard University Archives and other sources to discover, not just the answer to that question, but the entire history of Harvard’s relationship with Japan. This effort, the Japan/Harvard Project, is sponsored by the Reischauer Institute of Japanese Studies and the Program on U.S-Japan Relations. On Friday (Feb. 20), she and Mari Calder ’02, a staff member and research assistant at the Program on U.S.-Japan Relations, presented the initial results of their investigation in a lecture titled “Harvard’s Japan Encounter: From Perry to Pearl Harbor.”

“It is a story that really has not been told before,” Pharr said. As she and Calder took turns unraveling the narrative with the aid of vintage slides from the Archives’ collection, it proved to be a tale full of fascinating personalities, moving human stories, and intriguing details.

The story begins in 1853 with the arrival of Admiral Perry in Tokyo Bay and the subsequent opening of Japan to trade and diplomatic relations with the West. In 1860, the Meiji government of Japan sent its first diplomatic mission to the United States, an event that triggered paroxysms of wonder on the part of many Americans.

“It was an astonishing event,” said Pharr. “Few Westerners had seen Japanese before 1860. They paraded through New York in full samurai regalia, and Walt Whitman, who was in the crowd, wrote a poem about it:

Over the Western sea hither from Niphon come,

Courteous, the swart-cheek’d two-sworded envoys,

Leaning back in their open barouches, bare-headed, impassive,

Ride to-day through Manhattan.”

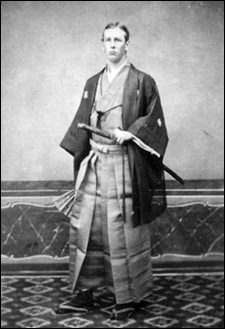

The exotic visitors moved others to poetic or impulsive gestures as well. In 1871, Henry Wadsworth Longfellow’s son Charles decided on the spur of the moment to take ship to Japan. While there he immersed himself in the culture, wore samurai attire, and returned with half a boatload of Japanese artifacts (many of them now at the Longfellow House on Brattle Street) and a tattoo of a carp on his back.

Around the same time, the Meiji government sent a 50-member mission to the United States under the leadership of statesman Iwakura Tomomi to study Western institutions. The group visited Boston in 1872, where they were lavishly banqueted by a group of dignitaries, including Harvard President Charles William Eliot. Oliver Wendell Holmes Sr. read a poem and Ralph Waldo Emerson gave a speech in which he declared, “Japan is full of romance to us.”

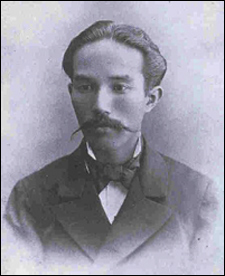

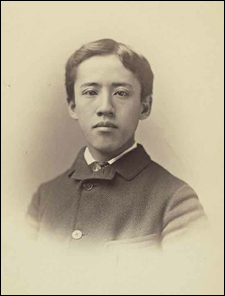

This was also the year that the first two Japanese students arrived at Harvard. Both enrolled in the Law School, earning degrees in 1874. One of them, Inouye Yoshikazu, aspired to a military career, hoping to emulate his idol, Napoleon. Oliver Wendell Holmes Jr., the future Supreme Court justice, tutored him along with another Japanese student, Kaneko Kentaro, who later helped draft the Japanese constitution in 1889. But after earning his law degree, Yoshikazu found it very difficult to readjust to life in Japan and he committed suicide at the age of 26.

But Yoshikazu’s fate was the exception among early Japanese students at Harvard. His Law School classmate Megata Tanetaro became head of taxation in Japan’s finance ministry. One of the first Japanese undergraduates, Kikkawa Chokichi, Class of 1883, graduated 47th in a class of 211 and was secretary of the Signet Society. He later wrote that his four years at Harvard stood out as the “brightest period” of his life.

A second wave of Japanese students began arriving in the first decade of the 20th century. Most of them were children of wealthy families and were able to access not only Harvard’s intellectual resources but its social opportunities as well.

“At a time when Jewish and African-American students were excluded from finals clubs, Japanese students were accepted into these and other exclusive societies,” said Calder.

Among these students was Matsukata Otohiko ’06, known by his classmates as “Oto,” who was a member of the Delphic Club along with Franklin Delano Roosevelt ’04. Another Japanese student was manager of the baseball team on which JFK’s father, Joseph P. Kennedy, played, and was a fellow member with Kennedy of the “H-Men.”

Japan’s victory in the Russo-Japanese War in 1905 increased the country’s prestige and popularity in America. Law School graduates Komura Jutaro and Kaneko Kentaro joined with President Theodore Roosevelt in negotiating the Treaty of Portsmouth, which brought an end to the conflict.

The growing prestige of Harvard among educated Japanese can be gauged by the visit of President Eliot to Japan in 1912. He was accorded full honors and enjoyed a one-on-one meeting with the emperor.

In 1913, Anesaki Masaharu, a professor at Tokyo Imperial University, became the first Japanese visiting professor at Harvard, offering courses on Buddhism as a member of the Philosophy Department.

In 1919, Yamamoto Isoroku, who later planned the attack on Pearl Harbor, came to Harvard to study English. He received only a C+ in the course but spent his free time to advantage by hitchhiking to Texas, where, by some accounts, he gathered information on America’s oil industry.

In 1934, the Harvard baseball team traveled to Japan where they were defeated 17 to 2 by the team from Waseda University. Despite their victory, the Japanese team gallantly presented the trophy to the Harvard players. It is still held by the Harvard Athletic Department.

The number of Japanese students at Harvard began to taper off in the 1920s and bottomed out in the 1930s as American sympathy turned against Japan in response to its incursions into China. By 1939, sentiment against Japan had grown very strong among Harvard students, Pharr said, culminating in a call by the student government for a boycott against Japan.

When Japan attacked Pearl Harbor in 1941, there were only three Japanese students at Harvard. Two were graduate students who, because of their embassy ties, were immediately seized by the FBI and removed from campus. The lone undergraduate, Tsurumi Shunsuke ’42, was confined to his dorm room and later transferred to a cell in the Charles Street Jail, apparently because the FBI agents who questioned him were troubled by his assertion that he supported neither the United States nor Japan.

During his incarceration, he finished his senior thesis on the pragmatism of William James and received his A.B. degree in 1942. He later returned to Japan on a prisoner exchange ship and has since become a well-known intellectual and social critic.

“He was simply in the wrong place at the wrong time,” said Pharr.