Dana-Farber scientists discover natural blocker for HIV-1 virus

Could lead to new strategies for preventing infection that causes AIDS

Researchers at Dana-Farber Cancer Institute have identified a protein in Old World monkeys that blocks infection by the human immunodeficiency virus (HIV-1). The finding could lead to improved animal models of AIDS for research and suggests that a similar molecule known to exist in humans might be exploited for prevention and therapy.

Named TRIM5-alpha, the blocking molecule may be the first example of an innate, previously unknown arm of the immune system that patrols the body for viruses and, if they enter a cell, prevents them from causing harm.

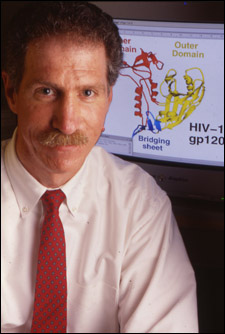

“This is the first glimpse of a form of intracellular immunity made up of natural factors that specifically and potently block retroviruses such as HIV-1,” says Joseph Sodroski, a professor of pathology at Harvard Medical School (HMS) and senior author of a paper appearing in this week’s issue of Nature. The lead author is Matthew Stremlau, an HMS graduate student. “Our finding expands our vision of what we might be able to manipulate to block the very early stages of HIV-1 infection,” Sodroski says.

Human cells contain a similar TRIM5-alpha protein but it is less effective than the monkey version in blocking HIV-1 infection. It’s possible that the potency of TRIM5-alpha differs among individuals because of genetic variations, which may explain why some people infected with HIV progress rapidly to AIDS, while others have remained healthy for decades.

While therapeutic use of the finding remains speculative, says Sodroski, researchers might find ways to increase effectiveness of the human TRIM5-alpha molecule, or, conceivably, administer the more potent monkey version as a therapy.

TRIM5-alpha proteins reside in “cytoplasmic bodies” inside HIV-1 target cells. The discovery begins to shed light on how the virus, once it has breached the cell membrane, uncoats and converts its genetic material, RNA, into DNA for replication. In a key step in the process, the inner core of the virus sheds its capsid – a protective coating that encloses the virus’ genetic material and replication enzymes – in preparation for reverse transcription. How this happens has been a mystery until now. Sodroski and his colleagues have shown that TRIM5-alpha recognizes specific viral capsids and, in as yet unknown ways, disrupts proper uncoating of the capsid. By blocking this step, TRIM5-alpha renders the virus unable to reach the genetic machinery in the host cell’s nucleus, and the infection fails.

The existence of TRIM molecules (for TRIpartite Motif) has been known for a number of years but not their functions. The identification of TRIM5 as a virus blocker came to light when Stremlau and Sodroski set out to discover the factor that efficiently prevents HIV-1 from infecting Old World monkeys (baboons, macaques, and mangabeys from Africa and Asia) – and is a hurdle to making models of human AIDS in these monkeys.

Authors in addition to Stremlau and Sodroski are Christopher Owens, Michel J. Perron, and Michael Kiessling of Dana-Farber, and Patrick Autissier of Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center.