‘Trays’ in Gund Hall serve up design delights

Ideas are contagious in open environment

Abby Feldman has a Laurel and Hardy screen saver with photos that change every five seconds or so. There are the boys in “Sons of the Desert.” There they are in “Another Fine Mess,” “Way Out West,” “Babes in Toyland.”

You express your appreciation for this bit of high-tech nostalgia, and in response she gestures toward a nearby bulletin board at a pantheon of old-time comedy duos, variations on the Laurel and Hardy paradigm – Abbott and Costello, Gleason and Carney, and a gaggle of others.

“Oh, yeah,” she says, “the fat guy and the skinny guy.”

She says it a bit wearily, as if the fat guy and the skinny guy have been weighing on her mind of late, keeping her up at night. As in fact they have. She has been meditating on these mismatched funnymen as a way of discovering the essence of her design project, a huge auditorium consisting of two conjoined protuberances that rise out of the landscape like a bulbous, segmented slug. Built above a marsh, the structure also represents an interpenetration of the natural and human-made worlds.

“The roof of the auditorium is covered by grass. The idea is that the marsh is invading the city, disintegrating the architecture.”

Contemplating Laurel and Hardy as a way of conjuring up a new architectural design may seem like a bizarre procedure in some areas of the world, but here in the trays it raises no eyebrows.

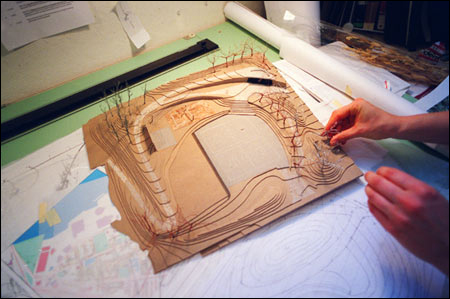

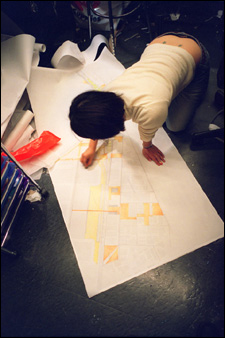

The trays are the tiered workstations under Gund Hall’s sloping glass roof where students at the Graduate School of Design (GSD) work on their projects. Stand at the highest level and look down, and the vista that confronts you has almost the impact of a natural wonder, a Grand Canyon of creativity. Perched on five levels, students are cutting intricate shapes from cardboard and Styrofoam, setting tiny trees beside basswood office buildings, inscribing streets and walkways on sheets of Bristol bond.

“Everyone is under one roof,” says Begüm Bengü, a third-year architecture student from Turkey. “You can look down and see everybody’s work. The intention is to erase privacy, to make a statement that architecture should be publicly presented and publicly defended.”

The lack of privacy creates a culture marked by the rapid diffusion of ideas. Let someone adopt an exciting new material or technique, and suddenly everyone is using it, from the innovator’s partner (or “butt-mate,” to use GSD slang) to students on the farthest edge of the great unencumbered expanse.

The faculty contributes its share of new ideas as well. Bengü is excited about the emphasis Toshiko Mori, chair of the Architecture Department, has placed on new materials and technology. Bengü’s final project, a high-rise museum designed for New York City, resembles a stack of off-center platforms that derive their stability from a fabriclike outer skin. The emphasis is on finding original ways of incorporating methods and materials, not slavishly copying.

“We’re trained to be innovators,” Bengü says.

Her butt-mate, Mayu Endo, agrees. Her project is on a grand scale, more urban design than architecture, which is fine, since moving beyond disciplinary boundaries is another way of courting creativity. Endo’s scheme is nothing less than a renovation of the waterfront of Tokyo, her hometown. She wants to build new residential neighborhoods atop giant floats like the ones used on offshore oil drilling rigs.

“There might be some inconvenience because people would have to use boats, but my argument is that they would be closer to natural conditions, it would stop car usage, and the result would be the greening of the city.”

As one moves from workstation to workstation, seeing in these tiny scale models the potential for new buildings, new neighborhoods, new parks, it becomes clear that this concrete hillside buzzing under its glass canopy is no mere professional school, but a powerful engine of innovation where bold ideas take a first giant step toward actuality.