Monsters, tooth fairies, God, and germs!

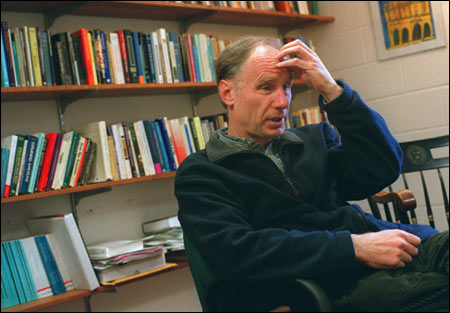

GSE Professor Paul Harris probes how children make sense of what they’re told

Young children receive an enormous volume of information – from the identity of their biological parents to names for animals to facts about the world around them – by testimony: Someone tells them that the family pooch is called a “dog” and that Mom and Dad are, indeed, Mom and Dad.

But since they have no other way of learning this information, what’s to prevent us from telling them that Fido is Dad? Couldn’t we take advantage of children’s naïve young minds to perpetuate lies for fun and fancy?

Not likely, says Harvard Graduate School of Education (GSE) Professor Paul Harris. A developmental psychologist, Harris argues that children as young as

Read an

interview with Paul Harris

preschool age can discern whether or not they’re hearing the truth, even in a domain for which they have no previous knowledge, by accurately judging the reliability of the person who’s telling them.

“Particularly among 4-year-olds, but also among 3-year-olds, they’re selective,” he says. “They come to trust somebody who seems to tell the truth, and to mistrust somebody who’s not.”

In collaboration with two postdoctoral fellows, Melissa Koenig and Fabrice Clément, Harris created experiments in which a pair of speakers – people in one case, puppets in another – presented various claims to the 3- and 4-year-olds. First, the speakers showed the children familiar objects, such as a shoe, a cup, and a spoon. One speaker identified them accurately; the second speaker misidentified them.

The speakers then showed the children an unfamiliar object – an obscure geegaw from a hardware store. The first speaker, who had correctly named the shoe, cup, and spoon, called it a “modi.” The second speaker, who had wrongly identified these familiar items, called this new item a “toma.”

The majority of the children accepted the name given to them by the speaker who they knew to tell the truth. “They’ll choose to call it a ‘modi,’ if that’s what the hitherto reliable speaker called it,” Harris says. Even though the item was completely novel to them, the children managed to judge, by assessing the veracity of the speaker, the truthfulness of the testimony they received.

Imagination and testimony

Harris’ research on testimony draws upon his previous work on children’s imagination, research that resulted in his book “The Work of the Imagination.”

In that book, he says, “I tried to show that in all sorts of relatively pedestrian ways, children use their imagination, just as we adults do. It’s not something that’s reserved for flashes of inspiration or daydreaming or creativity.”

He learned, for instance, that by preschool age, children were able to hear a story and use their imaginations to compare the story as told with what might have been, or what could be in the future.

Harris claims that children also use their imagination to learn from testimony: They can make sense of something that they did not encounter or experience directly. Children as young as 3 or 4, he discovered, possess this skill. “They can learn a great deal by virtue of just listening to their parents or their older siblings telling them about events that they didn’t witness,” he says.

Yet if children learn so much from testimony, “to what extent are they gullible or credulous as some people have suggested, or do they have some in-built filters to make sure that they do not accept claims that are just outlandish?” asks Harris, indicating the query that led him to this new line of research.

The relevance of this work is not lost on anyone who’s studied history or the origin of species. Despite progressive educators’ push toward experience-based learning, Harris estimates that 99 percent of what children learn in school they learn by testimony. “It’s fairly important to try to make sense of the tools that children possess for winnowing this information, for scrutinizing it, for evaluating it,” he says.

Germs: Definitely; God: Probably

Harris continues to probe how children make sense of what they’re told. In one current study, he asks 4- through 8-year-olds about their notion of what really exists. “Even if you speak to a 4-year-old, they would make a pretty straightforward cut between … cats and dogs and rocks and trees, which they know to exist, and flying pigs and red elephants, which they know to be impossible,” says Harris.

But what about entities children can’t observe themselves but must rely upon the testimony of others to verify? Harris explored children’s ontological conceptions of scientific abstractions, like germs or oxygen, extraordinary entities like the Tooth Fairy or God, and magical creations like mermaids, monsters, or ghosts.

He found children’s beliefs in these abstractions lines up with the testimony they received. “With respect to germs and oxygen, for example, 4- and 5-year-olds are perfectly happy to acknowledge that other people believe in their existence, and that they themselves believe in their existence,” he says, although they’ll quickly admit they don’t know what germs look like. “Our assumption is that children listen to adult testimony and simply assume, along with their adult interlocutors, that these things exist.”

Children were somewhat less certain of the existence of God or the Tooth Fairy. And they can pick out another class of extraordinary creatures that they know doesn’t exist, making what Harris calls an “ontological cut” between God and mermaids or monsters.

Harris cautions that it’s too early for a full interpretation of the findings, but the conclusions he’s able to draw so far support his assumption that children learn from testimony.

“These children are learning a great deal about what exists in the world just by listening to what they’re told,” he says. “They also have quite good antennae for the degree of consensus that exists with respect to particular topics.”

‘Odd and exotic’

Harris, who joined the GSE faculty three years ago from a 20-year career at Oxford University, characterizes his work as “odd,” although he can point to similar lines of inquiry in philosophy and the history of science. In developmental psychology, however, the dominant paradigm is that children learn by figuring things out for themselves.

“What’s odd or exotic is my saying, ‘Testimony is important, issues of trust are important, we don’t know anything about it, we have to study this,’” he says. As children – and adults – face myriad sources of testimony, from the Internet to news media to political stumping, these issues of trust are gaining in importance, he says.

In education, Harris is cautious about the enthusiastic embracing of experience-based learning, noting that it potentially limits learning to what is at hand to experience. Here in Massachusetts, for instance, schoolchildren could gain a rich experiential understanding of the Pilgrims or the Revolutionary War, but how will they learn about Egypt except through testimony?

“Children’s imagination can take them an extraordinarily long way … it can certainly take them to ancient Greece and Rome,” he says. “I don’t think you should underestimate the extent to which children can travel with you just by telling them things.”